What Climate Scientists Really Think

Michael Gibson, Doug DeCelle

Below is a conversation that I had with Michael Gibson, Senior Acquisitions Editor for Environmental Studies with Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. True disclosure: Mike is my son-in-law and we had this conversation in the course of a family visit in his home in Athens, Georgia.

Mike has just returned from two noteworthy environmental and climate conferences: the American Society for Environmental History (in April) and Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment (an interdisciplinary conference of eco-humanities and environmental social sciences scholars in June/July).

Mike is not a climate scientist. But he understands the world of environmental studies and climate change publishing. He knows many of the authors personally. This gives him interesting access and perspective on this daunting problem. Sometimes what a specialist says in an offhand or non-technical way reveals insight into an issue that a specialist research paper can never quite state overtly.

There is plenty of that here. Especially at conferences, Mike spends a lot of time talking with and socializing with the people who have the best insights into what is becoming the most dire threat that humanity has ever faced.

The Conversation

Here’s what he’s hearing:

DD: Mike, tell me about your two recent conferences. What were you doing and how is it that you were able to speak with a number of recognized experts in climate change?

MG: I spent a week apiece at two conferences focused on environmental and climate research. I ended up wearing a couple of hats being the only representative from my company. I manned a book table with books from my company, Rowman & Littlefield. Conference attendees would stop by, examine and buy books, and of course engage in light conversation. I also had numerous acquisitions meetings, sometimes over meals, with authors of prospective books.

Authors and publishers are forever trying to find each other and collaborate over projects. This gave me plenty of informal, even personal, time where I got a chance to talk at length. The most illuminating conversations, for instance, occurred at receptions, author parties, or over meals. So after a long day of discussions of new projects, research, sales, etc., I’d sit at a dinner table with someone. We’d have a glass of wine and relax. And in this atmosphere, they’d talk unguardedly. Again and again I was struck by what they are saying about where climate change is taking the planet and what we are in for.

Above all, they are in agreement. There is no doubt whatsoever among experts that the climate is changing, warming – with compounding and feedback effects – and that these changes will likely result in horrible consequences for all living things. The process is ultimately driving toward the extinction of humankind.

DD: How long do they think this will all take?

MG: While there’s a degree of variability of when the worst scenarios will really be a reality, there is a basic sense that a century is the red line – and that line is really coming closer.

Actually, what they’re seeing is alarming evidence that temperatures are rising faster and ice melting more quickly than even recently projected – polar melt and ice sheet collapses, for instance, are eclipsing the predictive models from just a couple years ago.

But it’s pretty certain that as the next few decades roll by the average weather will hit or even eclipse the “threshold” temperatures (for instance –several high temp records in places like Alaska and Northern Europe have already shattered all-time highs by nearly 5F). Not even talking about human extinction, current trends are already on track to bring sea level rise, crop failure, massive animal extinctions, displacement of populations from uninhabitable areas (eco-migration), and even collapse of governments in the next decades. We are concretely facing water and food shortages even in the next handful of years.

DD: And they believe, when they are not public speaking or writing in their books, they honestly believe that the extinction of humanity is in the offing?

MG: It’s a very real possibility – and one that has been known in the community for quite awhile, maybe even going back 20-30 years. At this point, they are actually a little weary of sounding an alarm that isn’t being heard. There’s even a sense of resignation to the inevitability of it all. More than one of these academics or scientists in informal conversation simply said to me, “More or less, we’re fucked.”

DD: What about the hoax theory which holds that the end-of-the-world reports are alarmist and designed to scare the public into accepting heavy-handed governmental control, which hampers business and limits people’s freedoms?

MG: No one thinks it’s a hoax, false alarmism, or statist propaganda. I talked with nearly 200 people at these conferences, and not one expressed any kind of doubt about the data and science.

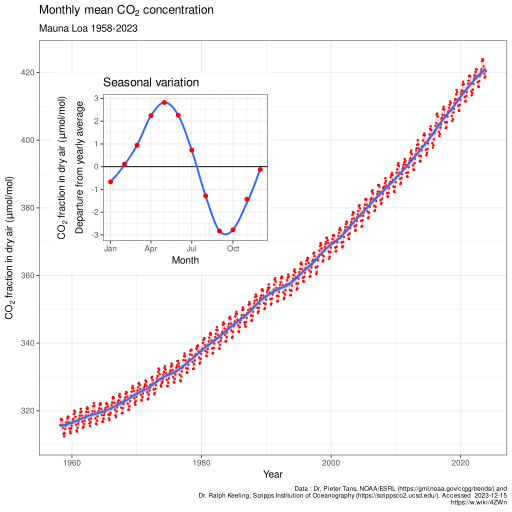

Denialism or doubt wasn’t anywhere in sight. There’s a clear consensus that the earth is warming due to carbon emissions. Carbon isn’t like soot that washes out of the air. Once it is in the atmosphere it pretty much stays there and accumulates. And that has compounding effects across various eco-systems, so that the longer this goes on, the more amplified it becomes.

You’ve got to understand that the realization that the world is being rapidly altered by climate change is not a recent discovery. The apocalyptic potential of this has pretty much been universally believed by the scientific community for a number of years. This is why the writers, scientists, and academics who I’m talking with are more resigned than alarmed.

If there’s alarm, it’s that very recent developments, such as rate of ice cap melting, ice sheet collapses, or temperature indexes, are outpacing predictive models and data from just a couple years ago – which means that these things are accelerating and happening faster than thought.

*That* they are happening, and *that* there’s a trajectory is unquestionable; but it is now happening at a speed that is quite beyond what was thought likely even just 2-3 years ago.

What’s more, the public sluggishness to face the crisis is so thick that America—especially America—is only slowly waking up to the fact that the droughts, floods, and storms we see in the news are due to a more fundamental shift in the weather. What has really not sunk in is that these are only going to get worse. And where it is all taking us is unthinkable – and in a very short time.

Even if the worst is a century off, in my own lifetime, as someone already squarely if not more than middle aged, will be famine, chronic resource shortages (even outright collapse in areas), large-scale displacement and migration. Some of the staple items that are part of my daily life won’t be available in 5-10 years; many will be gone in 20 years.

More to the point, many people around the world whose livelihood depends on growing/producing those items will face ruin – and hundreds of millions of people, if not nearly a billion, just within a decade or so, will have to leave their homes, countries, and abandon everything that constitutes their identities and realities because their lands will be under water (flooded) or so far from basic human resources that they can’t sustain life there.

The disruption, change, and fundamental alteration of our sense of life, community, etc. is that close. Really. It’s hard to even ponder the problem because we’ve never had the prospect of an ending to the human experience – and, for most Americans, there’s an unquestioned assumptionabout what the American experience, way of life, etc are.

Here’s something else I was seeing. The scientists are a bit intimidated by critics who charge that climate experts are alarmist and trying to manipulate the public. As a result, if anything, climate experts mute the most alarming information that they know about so as to avoid the charges of provoking hysteria or manipulating the public.

Alarmingly, the latest information about the advance of the warming climate suggests that it is developing faster than we feared. The ice melts in the arctic areas are more severe than was originally predicted. But what we hear, if anything, is much less dire than it could or should be. Those involved in this research or public presentation are often threatened or intimated by the massively bankrolled campaigns that come out of certain political or private business/lobbyist quarters – and as a result, data is held back or so constrained that it doesn’t really capture the situation on the ground.

So scientists are guarded and want to protect their disciplines against what is sometimes ferocious ridicule. Some researchers and scientists, such as James Hansen and Michael Mann, have faced nearly career-ending series of litigation, harassment, and threat tactics from big-monied interests, such that many of those who are engaged in this research self-censor and suppress in public-facing statements or pronouncements.

If anything, the true extent and reality of this is self-contained within the research community. Some are waiting to see what happens with current lawsuits pending around cases involving fossil fuel companies who blocked data reported by their own scientists that showed much of this information 30-40 years ago from being disclosed publicly – but there’s not much expectation. The money and strategies involved in suppressing data and controlling public discourse is staggering.

Just one example – if measures had been taken around the time of the Kyoto agreement in 1992, we’d be in a very different situation, perhaps a fully sustainable one; but, the political reaction and mobilization in reaction to that was so significant and coordinated, that we are in a very different world and climate because of that now nearly 30 years later.

DD: There must be some hope somewhere. I mean, what if everybody gets on board and we manage to bring CO2 emissions way down rather quickly?

MG: Right. Yeah, definitely get this – and hope is an important element. I really wanted to come away from this with something to latch on to. That’s really why I tried to spend time talking with these folks in a more informal way and met with them for meals, drinks, etc.

When I took over this role, I did a deep dive into key literature, resources, and research as a way of orienting myself to the field (especially since I didn’t have an eco-studies background). And that research endeavor left me in a place of not seeing “immediate” fixes, and even with a sense of despair.

The key findings in the major research, especially once I got into the eco-science journals and monographs, really collapsed the sense that there’s ‘quick fix’ or ‘silver bullet’ solution – and actually really corresponds to the informal presentations I encountered at these conferences.

But, yeah, again, one of the motivations to really talk to as many folks as possible at these conferences, besides my editorial interest, was to see if there was a constructive or remediable theme that surfaced. And, unfortunately, that was not the case.

What I heard – repeatedly and uniformly – was that, the scale and scope of the situation is beyond a single solution; if anything, the best outcome would be a global mobilization and mass-scale set of movements around multiple ‘fix points’ – and these would have to far exceed the kind of population- and industrial mobilizations that happened in WWII.

No single nation, country, etc. can do it. It requires the equivalent of a global-scale “Allied” mobilization. And that, unfortunately, at this point, is, at best, to stave off or modulate the worst scenarios in front of us. If we don’t do this, well, there’s that phrase I heard multiple times.

DD: Well, what about this idea I just heard about, where if we could significantly re-forest the planet, that we could suck, like a third, of the carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and re-sequester it in the soil?

MG: This is an idea that has caught attention recently and has become prevalent in the news cycle in the last few weeks even. It’s not entirely new idea, actually – versions of this have been proposed by exponents of what’s called the ‘rewilding’ movement going back to the 70s (and even earlier). That’s not to say there’s no merit to it. In fact, this kind of solution, especially enacted on a massive scale, could have a lot of positive benefits, especially given how straightforward, simple, and cost-effective it can be.

This would especially be the case if a mass-scale reforesting plan was coupled with widescale, if not global, elimination of livestock/mass-agriculture and conversion to an equally scaled public transit system (which would also involve moving most or all of on-land trade/commercial shipping systems to underground, in which things like highway systems and most roadways are turned into greeneries).

In other words, ‘re-foresting’ in a theoretical sense harbors a lot of potential; but, the crux of the issue is both the scale of the problem and the scale of the solution. For this to be a real solution, it would require a massive transformation of our ways of travel, settlement, transportation, infrastructure, trade, etc.

*If* there’s a possibility, I think there’s more positive evaluation of this suggestion on the theoretical plane, but the scale, investment, and degree of change that this option would necessitate truly to address the problem is one that will take a revolution far beyond that which even Bernie Sanders has in mind (or would be willing to lead); as well, it’s something that should have been pursued decades ago to really achieve the necessary impact – trees take decades to reach maturity, and if we had done this back in the 80s or 90s, we’d be at a place where massive reforestation and tree-growth would be generating near-maximal effect.

At the same time, here’s the real take away – if we don’t do something like this, which is even in *some* doubt among the community, the economic, political, social, and global costs are nearly incalculable. At this point, inaction, apathy, and even incremental reforms, are vastly more costly than undertaking the so-called extreme measures, like the ones mentioned here; and those bills will come due sooner than anyone thinks.

DD: Or, what about technological solutions, such as geo-engineering projects, or tech-mitigation efforts, such as injecting sulfur-based solutions into the atmosphere to block sunlight and instigate cooling, or spraying the oceans with refractory chemicals to reflect rather than absorb sunlight?

MG: Good question. And I had that same query in mind. I asked about this repeatedly at both conferences. The response was universal – and the consensus was this is a path we should completely reject. The reasons are various, but basic. For one thing, the tech solutions themselves are theoretical and experiment – and at this point still in phases that are wholly unsuitable for cost and scale.

But, more alarmingly, the actual effects to the environment, eco-systems, etc., are wholly unknown. I heard this repeatedly that this is the ‘Frankenstein option’ – once we pursue something like this in actuality, we don’t know what we will unleash and we don’t know how to manage it.

Even more, we can’t undo it. Once you change the environment in this way, you can’t just stop doing it if it doesn’t work the way you think it will, etc. – you have to keep doing it perpetually or the consequences are even worse. As well, while the ‘rewilding’ idea has more merit to it, some of the criticisms are similar here – both have possible unforeseen negative impacts on local, regional, and even continental eco-systems. Although ‘reforesting’ is a more strongly positive option, both have the problem that when you significant intervene in an eco-system, there are knock-on effects in terms of weather patterns, resources, habitability, etc.

The tech solution is far more catastrophic in regard to the unknowns and commitments once we go down that path, though. While we like to look to Silicon Valley in this age for ‘disruptive’ advances, it’s a sci-fi pipedream.

Everyone I talked with said nearly the same thing – not developed enough to really address the problem; far too expensive to apply to scale; and WAY too invasive/alterative to be an actual solution (and over and over I heard the heard the ‘Frankenstein’ warning)

DD: So what’s it like for the scientists who are facing this? They’re the ones who are looking at, what they believe to be the end of the human race. What’s that like?

I think of these kids who are following in the example of the Swedish girl, Greta Thunberg, who are genuinely alarmed and frightened by what is unfolding and what their own prospect is. Children have figured out that their later adult years will be pretty grim with unbearable temperatures through broad ranges of the planet together with famine and storms and they are understandably scared. Kids seem to get it. What are the scientists feeling?

MG: They don’t seem terrified. Maybe because they’ve been living with the end-of-world potential of climate change for decades now. They have been sounding the alarm about what is developing since the 1980s, if not earlier.

They’ve been consistently ignored. Overall, I would say that they seem to strike a balance between true recognition of the reality and humor, if not hope. I can’t say that I found a *actual* hopefulness or source of concrete hope, but I think they’ve largely mastered living a truly dialectical existence: the data shows what it shows, and we all have to go on living with that reality coming ever closer.

Faith and the Climate Crisis

DD: Now you have a theological background. When I read say David Wallace-Well’s Uninhabitable Earth I have an enduring feeling that climate change is literally a problem of biblical proportions.

It’s encouraging to me that the Old and New Testaments envision the prospect of the end of the world. Creation and human life within Creation are certainly not guaranteed. God can withdraw God’s sustaining, preserving presence. It’s good that there is some place where our situation parallels another one. But the Bible is essentially hopeful. The earth is created good. God is seen by the biblical authors as faithful.

And the vision of the end of all things, say in the Book of Revelation, gives us a world that is perfected, beautiful, and filled with God’s presence. This current secular future prospect leads us to a fundamentally different conclusion—with plenty of evidence to back it up. What do you do with that?

MG: The science behind climate change, which reminds us that virtually all of life has collapsed five times before, really makes vivid that humans are much less central and permanent than Christian religion assumes. It is reassuring that we’re not talking about the destruction of the earth itself or all of existence. But we are looking at a complete reset of life with pretty much an end of life—including human life—as we know it.

But you’re right that the science appears to be completely incompatible with the Christian view of the nature of the world. More than before we’re forced to choose one or the other. What I would say are the takeaways for religion/theology are the following.

First, religion/theology has to deal with the total de-centering of human beings, and human existence, from its construal of the world, the meaning of history, and teleology. That the entirety of human existence is a but a mere sliver of the history of life and the history of world, let alone the universe, is extremely consequential.

That the extinction of humanity is now a real possibility, if not a certainty, is only the latest in a series of extinctions – as you mentioned – in the full history of life on earth – and even there, all other eras of life far eclipse the duration of the human era (e.g., dinosaurs lived 150x the length of the human era along, and have been extinct nearly 100x the amount of time that humans have existed, counting the earliest hominids).

Second, and related, eschatology and teleology need to be totally rethought – if religion is predicated on the centrality of the human experience, its extinction is a very real nettle. As well, as with the first point, if religion/theology in general, and eschatology/teleology subsequently, fail to account for the vast trajectories and complexities of life prior to the human era, they fail both to address the meaning of the current era of life and to adduce what the concrete structure of hope is in its collapse and on its way to the next stage.

Third, religion/theology very much needs to articulate a concrete vision of what comes after. I don’t mean here the afterlife, but what comes after human extinction. Currently, because of the foregoing, there’s no religious/theological vision for an earthly life *after* humanity.

Yet, “apocalyptic” conditions and occurrences have happened before – in which large-scale, complex systems of life, that existed for extreme durations of time, experienced complete collapse and extinction; these systems actually did not return, but, after very extensive stretches of time, gave way to quite different forms of life.

Religion/theology, in this era, needs to address not only the possible extinction of human existence entirely, but also the very real – and likely – possibility of further eras of vastly different and equally complex life (perhaps many more eras).

Last, in the present stage, religion/theology needs to develop quite sharply the prophetic edge that is its most vital and salient resource: that element that assails the political, economic, social, and even religious structures that uphold the status quo; that calls out the forces that alienate, exploit, and marginalize; and that agitates and even aligns/mobilizes with revolutionary movements that militate for widespread and wholesale change, transformation, and transvaluation.