The Warmth of Other Suns: Summary and Notes

By Harold D. Young

Notes on Isabel Wilkerson’s book, Warmth of Other Suns.

Isabel Wilkerson won the 1994 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing as Chicago Bureau Chief of The New York Times. The first black woman to win a Pulitzer Prize in journalism and the first African American to win for individual reporting.

The Great Migration occurred over 6 decades (1915-1970), with 6 million blacks leaving the South.

If there was a single precipitating event that set off the Great Migration, it was World War I. Some 555,00 colored people left the South during the decade of the First World War – more than all the colored people who left in the five decades after the Emancipation Proclamation.

The masses did not pour out of the South until they had something to go to. During the first decade of the Twentieth century, some 194,000 blacks left the border and coastal states. After Jim Crow laws closed in on blacks in the 1890s, the trickle of blacks migrating to the North became a stream of blacks who settled in relative anonymity in the colored quarters of primarily northeastern cities, such as Harlem in New York and in north Philadelphia.

White planters would lament about the Exodus of coloreds. Written in the Columbia State of South Carolina, “black labor is the best labor the South can get. No other would work long under the same conditions.”. A Georgia plantation owner once said, “It is the foundation of its prosperity… God pity the day when the negro leaves the South.”

When the South woke up to its once guaranteed work force, it tried to intercept it.

“Conditions recently became so alarming – that is, so may Negroes were leaving, wrote an Alabama official, that the state making anyone caught enticing blacks away – labor agents, they were called – pay an annual license fee of $750 “in every county in which he operates or elicits emigrants” or fined as much as $500 and sentenced to a year’s hard labor.

Macon Georgia required labor agents to pay a $25,000 fee and secure the unlikely recommendations of twenty-five local businessmen, ten ministers, and ten manufacturers in order to solicit colored workers to go North.

Blacks trying to leave were rendered fugitives by definition and could not be certain they would be able to make it out. In Brookhaven Mississippi, authorities stopped a train with 50 colored migrants on it and sidetracked it for three days. In Albany, Georgia, the police tore up tickets of colored passengers as they stood waiting to board.

Washington, D.C. was the honorary North. One could escape the fields and work indoors in offices and sit on buses anywhere they chose.

Summary

The Great Migration is, finally, a testament to the courage, resilience, and dignity of the people who risked everything to gain some measure of the freedoms promised them in the Declaration of Independence and the Emancipation Proclamation—even as they faced new difficulties in the North. The book sheds new light on one of the most important demographic upheavals in American history and shows just how dramatically American culture has been changed, and continues to be changed, because of it.

By focusing on individuals as well as census figures, archives, and other historical documents, Wilkerson captures with unprecedented vividness the lived experience of the Great Migration. Wilkerson lets readers feel the very texture of life under Jim Crow law—the constant fear and daily humiliations, both small and large: Robert Pershing Foster having to drive through three states before finding a hotel that will accept him; Ida Mae Gladney having to pick a hundred pounds of cotton a day, which was like “picking a hundred pounds of feathers,” and then getting cheated out of a fair wage; George Swanson Starling standing up to the orange grove owners and having to flee a lynch mob for doing so. The intimate portraits of The Warmth of Other Suns bring the book to life and convey the true depth of hardship and suffering of all who were swept up in the Great Migration had to endure (Penguin Random House Reading Guide).

The seeds of the book were sown within Wilkerson years ago, growing up with parents who had migrated from the South. Her mother was born in Georgia and father in southern Virginia, Petersburg.

Routes of Black Migration

- People from Arkansas, Alabama and Mississippi boarded the Illinois Central to Midwestern cities like Cleveland, Chicago and Detroit

- Those from Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas and Virginia rode the Seaboard Air Line up the East Coast to Washington, Philadelphia and New York

- Those in Louisiana and Texas took the Union Pacific to Los Angeles, Oakland and other parts of the West Coast.

Wilkerson, in the mid-1990s, set out to search for the people who had migrated from the South to the West and North.

The search led her to Mississippi Clubs, Masonic lodges, class reunions, union meetings of retired postal workers, bus drivers transit workers, Baptist Churches, Creole luncheons, Juneteenth Day Celebrations (commemorating the day the last slaves in Taxes learned they were free, 2 years after the Emancipation), senior centers, Louisiana Clubs, Texas Clubs, Sunday Masses, libraries, community meetings in Oakland, funerals and family reunions in Milwaukee.

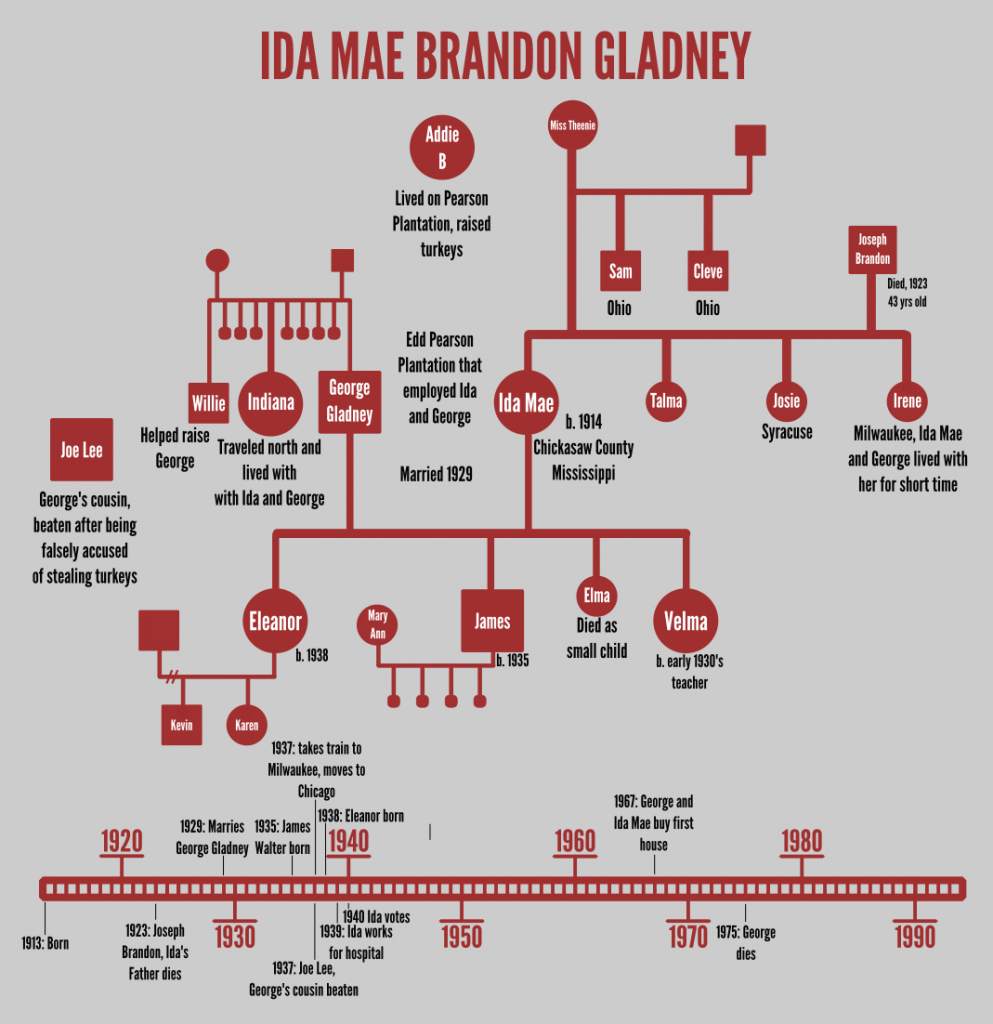

Ida Mae Brandon Gladney left Chickasaw Mississippi late October 1937

Leaving

Ida Mae tried to get the children ready for the trip up North. There was a nervousness about her. Her husband was settling up with Mr. Edd, landowner, for a year’s work. None of them had been on a train before.

Beginnings

Ida Mae’s suitor, David McIntosh came to pay Ida Mae a visit after church on a tall red horse. Not to be outdone, George Gladney walked 3-4 miles, crossing railroad tracks to see her. Ida Mae’s focus on life events and single-mindedness makes her attractive not only to her suitors, but also as an attractive subject of Wilkerson’s Great Migration.

Ida Mae would accept the offer of marriage from George Gladney. He was 23 and she was 16.

It was clear that in Mississippi, an invisible hand, ruled the lives of all colored people. Whites were in charge and coloreds had to obey.

On an occasion when Ida Mae accompanied Ms. McClenna in Okolona to help her sell eggs, the lady said, “you cant’s bring that nigger in…” In her response to Ms. McClenna’s question “[d]id you hear what she called you,” Ida Mae said, “they call you so may names. I never pay it no attention.”

When Ida Mae was thirteen, she learned of two brothers who were hanged for saying something to a white woman. After the boy’s funeral, the family packed up and went to Milwaukee. She recalled that this impactful event was a signal to her that there was in fact a window out of the asylum.

The Civil Rights Act of 1875 explicitly outlawed segregation. After Reconstruction (1865–77), the Federal government took over the South in monitoring compliance with the Emancipation Proclamation:

- Blacks could marry, go to school, if available, open businesses, run for elective office.

- There was open seating on streetcars in the 1880s. However, in 1891 Georgia demanded separate seating by race.

- There were white waiting rooms and colored waiting rooms for men and women. So, four waiting rooms had to be constructed at a considerable expense to enforce racial separation.

- There were curfews for blacks. Blacks had to be off the streets or risk being arrested or worst.

- Plessy v. Furguson (1896): Mr. Plessy purchased a ticked on the Louisiana Railroad, and set in the white only section. He was arrested. The case would end up in the Supreme Court. The Court ruled separate accommodation was acceptable and constitutional.

- The concept of “Separate but Equal,” under Plessy, would remain the law of the land for 60 years until Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas (1954). The Court ruled in Brown in a unanimous (9–0) decision that separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” and therefore violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Politicians began anti-black sentiments all the way to the governor’s mansions throughout the South and to seats in the US Senate. Kames K. Vardaman, the 1903 white supremacy candidate in the Mississippi’s governor’s race stated: “ If it is necessary, every Negro in the state will be lynched.” He saw no reason for blacks to go to school. “The only effect of Negro education”, he said, “is to spoil a good field hand and make an insolent crook”

Fifteen thousand men, women and children gathered to watch 19 year old Jesse Washington as he was burned alive in Waco Texas, in May 1916. A father holding his son, a toddler, on his shoulders, stated, ”my son can’t learn too young.”

According to Arthur F. Raper’s book, Tragedy of Lynching (1933), one could be hanged or burned alive for such crimes as stealing hogs, horse-stealing, poisoning mules, jumping a contract, suspecting of killing cattle, boastful remarks, trying to act like a white person. Sixty-six were killed after being accused of insulting a white person. One was killed for stealing seventy-five cents.

It was around the turn of the century that southern state legislatures would pass laws regulating black lives – solidifying the caste system to keep whites and coloreds separate. The laws were called Jim Crow laws.

More often than not,sharecropping,left blacks with less than their share for which they had bargained. Landowners provided sharecroppers with land, seeds, tools, clothing, and food. Charges for the supplies were deducted from the sharecroppers’ portion of the harvest, leaving them with substantial debt to landowners in bad years. Sharecroppers would become caught in continual debt, especially during weak harvests.

Ida Mae and George were accused of harboring George’s cousin, Joe Lee , who allegedly stole turkeys of Mr. Edd. Joe Lee was found coming out of the back of Ida Mae and George’s home and was beaten unmercifully. Later the turkeys wandered back to Ida Mae’s and George’s cabin. The turkeys had been roosting in the countryside and came cawing and clucking before Ida Mae knew why Joe Lee was captured in the first place. After Joe Lee’s beating, Ida Mae and George decided that this would be the last crop they would be sharecropping for Mr. Edd or anyone else. This was a further incentive for Ida Mae and George to leave Mississippi.

Exodus

Ida Mae hoped that Mr. Edd would not attempt to stop her and George from leaving. George had purchased tickets in Okolona, a distance away from their home, so no one would notice them leaving and attempt to stop them. They first moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin with her sister, Irene.

Ida Mae and George did not know where they would work when they reached the North. What they did know was, they would never have to drag another sack of cotton on their backs through a hot, bearing-down field. As for Ida Mae, just riding the train with the grand, triumphant-sounding names, Silver Meteor, Broadway Limited, took the people to grand and triumphant sounding places and a little bit of that prestige could rub off on them.

Crossing the Mason-Dixon line was a thing of spiritual and political significance to the guardians of southern law and to colored people escaping it who knew they were crossing over.

Note: The Chicago Commission on Race Relations, after World War I, minorities were asked why they had left the South. A few responses were:

- Some of my people were there

- Persuaded by friends

- For better wages

- To better my conditions

- Better conditions

- Better living

- More work; came on visit and stayed

- Wife persuaded me

- Tired of the South

- To get away from the South

The Kinder Mistress

Divisions

There was a cultural divide between the North and South and the migrants paid a price.

An economist, Sadie Mossell, wrote of migrants in Philadelphia, “With few exceptions, the migrants were untrained, often illiterate and generally void of culture.”

“The inarticulate and resigned masses came to the city wrote E. Franklin wrote of the 1930s migrating to Chicago, adding “the disorganization of the Negro life in the city seems at times to be a disease.”

The migrant’s reputation had preceded them. It was not good. Neither was it accurate.

Migration scholar Everett Lee wrote, “As the distance of migration increases, the migrants become an increasingly superior group.”. Lee further wrote, migrants who overcome a considerable set of intervening obstacles do so for compelling reasons, and such migrations are not taken lightly. Intervening obstacles serve to weed out some of the weak and incapable.”

One of the myths migrants had to overcome was that they were bedraggled hayseeds, just off the plantation. Census figures paint a different picture. By the 1930s, nearly two out of every three colored migrants to the big cities of the North and West were coming from towns or cities in the South as did George Stalling and Robert (Pershing) Foster, rather than straight from the field.

Ta – Nehisi Coates commented on Warmth of Other Suns in the Atlantic Magazine, January 22, 2013, “The Great Migration was not an influx of illiterate, bedraggled, lazy have-nots. Wilkerson marshals a wealth of social-science data showing that the migrants were generally better educated than their Northern brethren, more likely to stay married, and more likely to stay employed. In fact, in some cases, black migrants were better educated than their Northern white neighbors.

In the 1940s and 1950s, colored people who left the South averaged nearly two more years of completed schooling than earlier waives of migrants in New York, Cleveland, and St. Louis and close to the percentage of whites in Chicago.

The percentage of post-war black migrants who had graduated from high school was as high or higher than the native whites.

Whatever their educational level, the migrants, “more successfully avoided poverty,” wrote Larry Long and his colleague, Kristin A, Hansen of the Census Bureau, “because of higher rates of labor force participation and other (unmeasured) characteristics.” Long and Hansen further wrote, “The migration of blacks out of the South has clearly been selective of the best educated,”. It is possible that the least capable returned, leaving in the North a very capable and determined group of migrants.”

Ida Mae was now pregnant and went back to Mississippi to have the baby. George was not able to find work in Milwaukee and moved to Chicago where his brother lived.

During their search for housing in Chicago, the color line had been clearly drawn. “Negro migrants confronted a solid wall of prejudice and labored under great disadvantages in these attempts to find new homes” wrote Edith Abbott, University of Chicago researcher.

These overcrowded colonies would be the foundation of the ghettos that would persist into the twentieth century. These were the forgotten island, the original colored quarters – the abandoned and identifiable no-mans-land that came into being when the least- people were forced to pay the highest rents for the most dilapidated housing owned by absentee landlords trying to wring the most money out of a place nobody cared about. Anyone in American new where these forgotten islands were: along a polluted stream in Akron, Ohio, in the Hill District of Pittsburgh; Roxbury in Boston; the east side of Cincinnati; the near side of Detroit; nearly all of east St. Louis; whole swarths of the South Side of Chicago and South Central in Los Angeles; and much of Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant in New York.

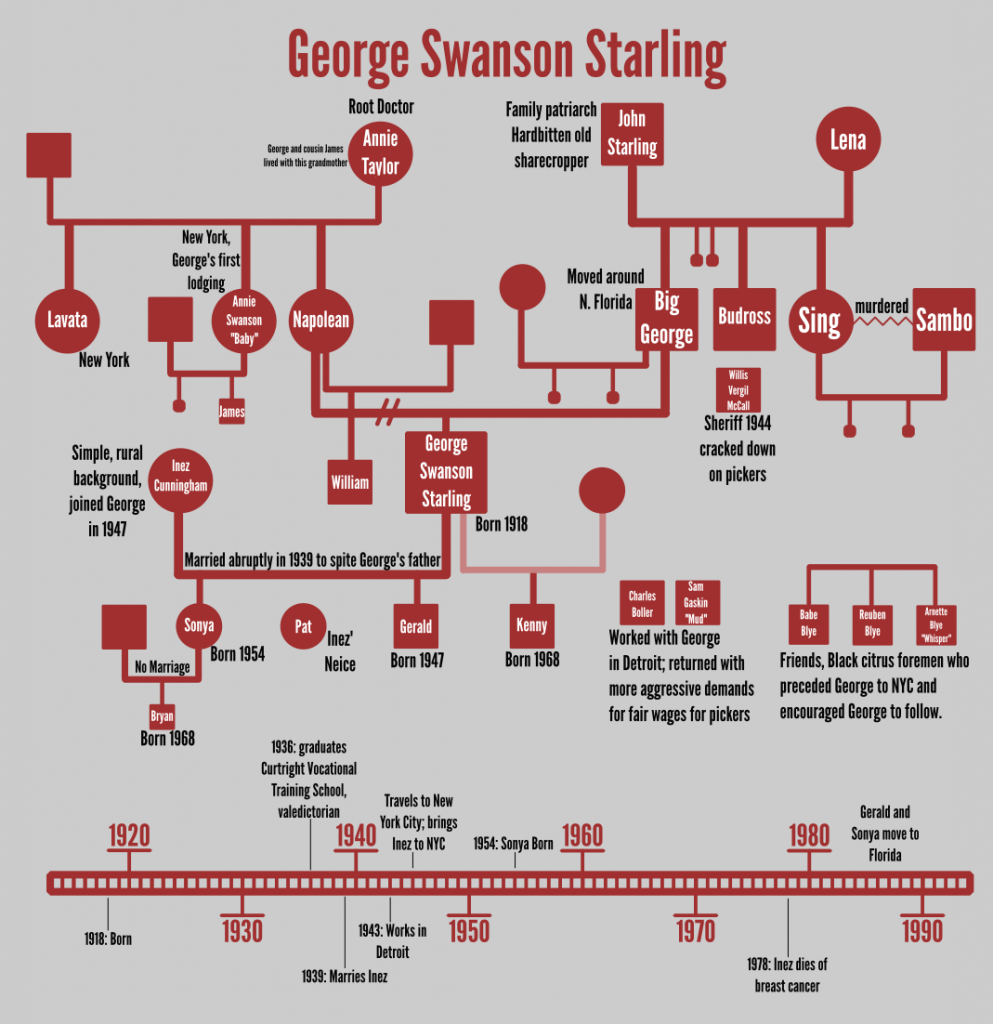

George Swanson Starling, left Wildwood, Florida April 14, 1945

Leaving

Schoolboy as the local pickers called George was boarding the Silver Meteor careful to board the train on the colored side of the stairs into the train, as if white stairs were sacred. He was packed into the Jim Crow car where the railroad stuffed luggage. George had no idea where he was going when he got to New York.

The planter’s word and his word alone that determined the proper credit due the sharecropper with what he was due. By the time the planter subtracted the “furnish,” that is, the feed, the fertilizer, the clothes and food – from what the sharecropper had earned from his share of the harvest, there was nothing coming to the sharecropper at settlement.

Many migrants who moved North found low wages and were force to live in tenements, in no small way, to accumulate and send money back home, for their family depended on the that money.

Florida went to greater extremes than other slave states in repressing of slaves: Slaves could not gather to pray, they couldn’t leave their plantations, even for a walk, without written permission from their owner. The penalty could be the back of their hands were burned or ears nailed to a post or their backs stripped raw with seventy-five lashes.

Florida, Mississippi and Texas took steps to begin imposing a formal caste system. Florida’s 1865 law set forth “ any negro, mulatto, or other person of color shall intrude himself into the railroad car, or other public vehicle set apart for the exclusive accommodation of white people, “ he would be sentenced to “stand in pillory for one hour, or be whipped, not exceeding thirty-nine stripes, or both at the discretion of the jury.”

These and other stories about the white mob that burned downed the colored section of Ocoee, Florida, when a colored man tried to vote, were passed down over the years. After burning of Ocoee, many blacks packed up and left, never to return.

School came easy to George. He began thinking about how he could escape Florida, maybe go to college. By graduation day, there were only six seniors in the graduating class of 1936, George was the valedictorian. George did not get much support from his father to attend college. He was accepted at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical State College in Tallahassee. His father did not provide financial support for him to return after his sophomore year.

Later, George met Inez Cunningham. In part, to get back at his father for not supporting him to return to school, he married Inez, from the other side of the tracks.

Beginning

George had plans to go to Detroit and promised Inez that he would send her to cosmetology school.

In Detroit, George found a job, working nights at a B-29 cargo factory. His job was to drill holes around hatch door frames. Beginning in 1943, a race riot started and lasted for a week with 34 dead and more than a thousand injured.

After the riots, George left to go back home to Florida to pick fruit. Having experienced fair wages in Detroit, George started organizing some of the fruit pickers. He negotiated for the pickers an increase from fifteen cents for a box of fruit to twenty-two cents a box. At some point, George convinced the pickers that they should walk off the job for higher wages. This infuriated the grove owners. George’s union activities caused a problem among owners of the fruit groves. Some of the coloreds who did not want to “buck the system” of the grove owners, told of George’s activities. George later learned that a plan was afoot to kill him by hanging. Fearing for his life, George told his father that the best thing for him to do “is to get out from around here.”

Exodus

George, Sam and Mud (pickers who supported George’s union activities) were leaving Florida. They decided to leave separately to avoid being observed.

George was finished with the South. Never again would he go back.

George found a seat in the Jim Crow car on the train, the first car behind the coal-fired locomotive. It was where the luggage and coloreds were placed.

Traveling outside of the South on trains, the “White Only” signs were removed and the reverse was true when colored passengers returned to the South.

The Kinder Mistress

George did not see himself as part of a great tidal wave. “I just knew that I was getting way from Florida. He said, “I was just hoping I would be able to live as a man and express myself in a manly way without the fear of getting lynched at night.”

George found a job on the railroad, as a coach attendant, making $100.00 every two weeks, more than he ever made as a fruit picker, but much less than whites made holding the same job. The job required that he worked twenty-four and forty-eight hour runs. He was still referred to as “boy” as the custom was in the white cars.

Harlem was a mature and well-established capital of black cultural life. Seventh Avenue was known for the “Stroll” where blacks would dress up as they saw themselves to be. Virtually every black luminary was living within blocks of the others in the elevator buildings up on “Sugar Hill” with the likes of Langston Hughes, Thurgood Marshall, Paul Robeson, Duke Ellison, Richard Wright, and W.E. Du Bois.

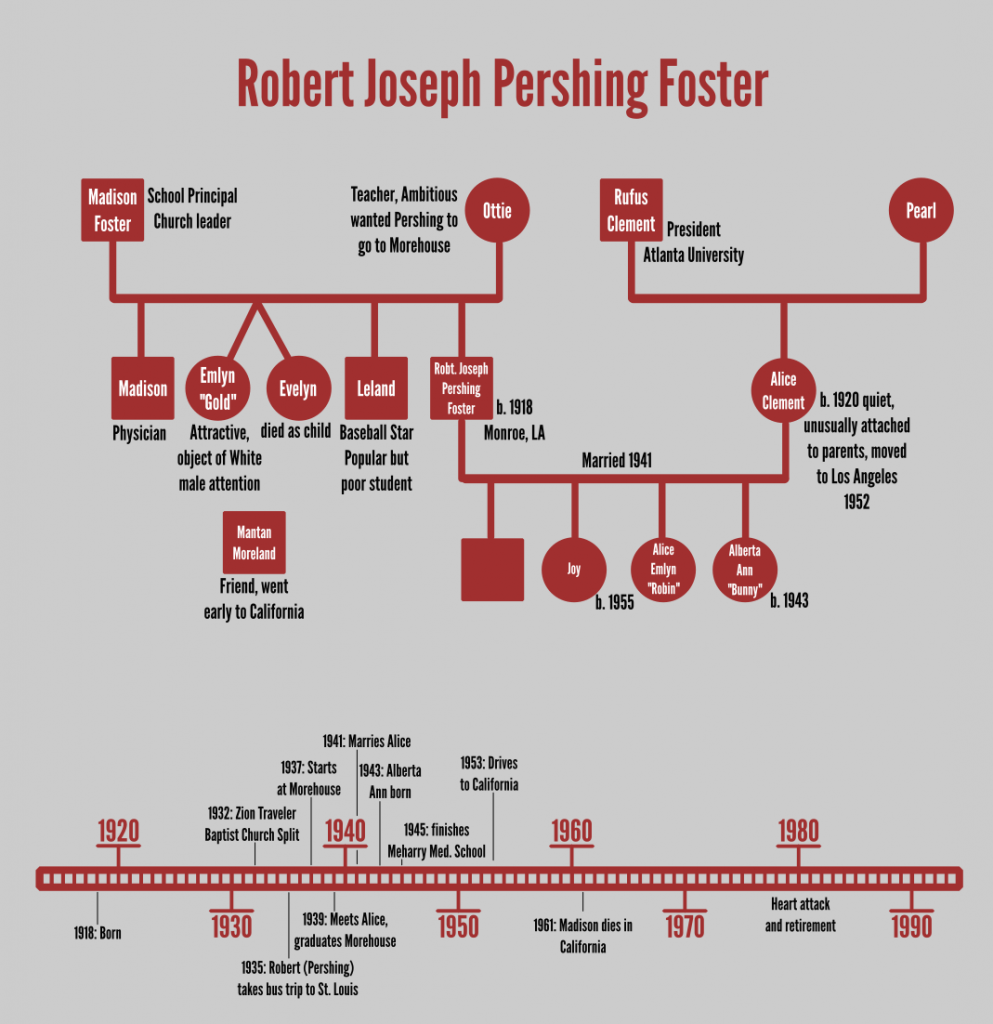

Robert Joseph Pershing Foster left Monroe, Louisiana April 6, 1945

Leaving

Pershing would pack his clothes, surgical books, medical books and chicken from the Saturday before. Perhaps Pershing would have stayed in Monroe had they let him practice surgery as he was trained to do. He knew he was as smart or as he thought, smarter than anyone else. Pershing didn’t know where he would end up in California, or how he would make a go of it.

Pershing felt as though he was playing catch up when he left in 1953 with a tide of people who had already rolled out. He drove west with a sense of urgency.

Beginning

Pershing was the last among four children of Madison and Ottie Foster. Mr. Foster was the principal of Monroe Colored High School. His wife, Ottie, taught seventh grade. They purchased a bungalow. Some Sundays Mr. Foster preached at Zion Traveler Baptist Church.

Pershing recalls that blacks were allowed into the movie house only through a side entrance. He also recalled his books from school were hand-me-down books. A new school was built in Monroe, but for whites only. There was no pay equity between white and black educators. White principals in the 1930s made $1,165 a year, colored principals received $499 each year, forty-three percent of whites. These pay schedules amplify the wealth gap between whites and coloreds. Whites wealth was ten times that of coloreds.

A fire broke out in the colored high school, causing substantial damage to the building. The city refused to provide funds to rebuild the school. Parents and teachers had to raise money themselves to repair the damage.

Pershing’s brother’s, Madison, gave him a trip to St Louis. Pershing was sixteen, just having completed the eleventh grade, which was a far you could go in school.

This would be the first time Pershing had left Monroe on his own. He traveled by bus. He noticed shingles designating “Whites” and “Coloreds.” Whites could pick up the shingles and move them further toward the back. He expected to see this and took his seat.

Virginia prohibited the two races from setting together on the same bench unless other seats were filled. In Georgia, the penalty for willfully sitting enjoyed in the wrong seat was a penalty of one thousand dollars or six months in prison.

Pershing was accepted at Morehouse, the most prestigious college for coloreds in the country. Going to Morehouse changed his personal trajectory. He enjoyed being among the upper class. Morehouse is where he would meet his wife, Alice Clement. Alice’s father, Dr. Rufus E. Clement, was President of Atlanta University.

Pershing finished Meharry Medical School in 1945 and moved to St. Louis to serve out his residency. Pershing had received a deferment during World War II. After the war, he reported to Fort Sam Houston, Texas for his training as a medical army officer. Pershing achieved the rank of Captain. Nonetheless, he felt the vail of Jim Crow still hovering over him.

He was effectively denied opportunities to care for white women patients who had gynecological and obstetrical problems. He had the credentials to handle these cases. After that ordeal, Pershing made up his mind that he was leaving permanently for California.

Exodus

The drive across Texas was the longest with no hope of lodging because there was no lodging for coloreds. The drive, restrictions, colored only signs, were particularly agitating to him as Pershing thought much better of himself.

About the same time, that Pershing was traveling to California another family was taking the same route. He, his wife and all but one child, were fair skin and could pass for white. At the first motel when the darker child was observed the family was not allowed to stay at the hotel. At the next hotel, the darker child was hidden from view and the family was allowed overnight accommodations.

After having been refused accommodations at three motels in Texas, Pershing knew that he would find it difficult when he reached San Diego. He asked where can I find a colored hotel? The man he had been conversing with said, “ I can tell you where a hotel is. There is a hotel right here.” Pershing said, I don’t want that. Just tell me where most colored folks stay. After arguing back and forth with the man, the man finally, gave him a name of a hotel, a place for colored people.

The Kinder Mistress

In Los Angeles, Robert found refuge with his mentor and Meharry Medical School Professor, Dr. William Beck.

Dr. Beck had a story to tell of his own. His father was ill in Louisiana with tuberculosis. There were no colored doctors around, and no white doctors would come out to the farm. His father died, and he decided then that he would become the doctor that didn’t exist when they needed one. When Dr. Beck moved his family to California, he found himself up against a different type of restriction from what he faced in Louisiana – restrictive covenants. The house that the Becks purchased had in its deed a covenant forbidding the owner in this all – white community, from selling their home to coloreds. Dr. Beck and wife went to court and won that battle over restrictive covenants.

Pershing, with a dollar and a half, in his pocket, accepted an invitation from Dr. Beck to stay with him. Pershing found a job with the Golden State Mutual Life insurance Company, the largest colored company in the west. Pershing did not enjoy the idea of just doing physical exams and taking patients’ urine and blood tests. One colored woman refused to be examined by him. This quickly taught Pershing the new realities of the West – coloreds had choices and they did not always want colored doctors.

Dr. Clement, Pershing’s father-in-law, was appointed to Atlanta’s School Board. The appointment placed a lot of pressure on Pershing, because he felt that he had never measured up to his father-in-law’s standards. Thereafter, he assumed a more aggressive and charming approach to lure more patients to his practice.

Notes on Isabel Wilkerson’s book, Warmth of Other Suns, focusing on the destinations of the three protagonists.

Unlike most migrations, the blacks who left the South were seeking full citizenship within their own country, rather than traveling to an entirely new land. The racial terror that reigned in the Jim Crow South—the daily humiliations, constant fear of violence, and the yearning to live a full and free life—drove them to make a perilous journey, risking their lives and livelihoods in the process.

There were two sets of similar people arriving in Chicago and other industrial cities of the North at around the same time in the early decades of the twentieth century—blacks pouring in from the South and immigrants arriving from eastern and southern Europe in a slowing but continuous stream from across the Atlantic, a pilgrimage that had begun in the latter part of the nineteenth century. On the face of it, they were sociologically alike, mostly landless rural people, put upon by the landed upper classes or harsh autocratic regimes, seeking freedom and autonomy in the northern factory cities of the United States.

But as they made their way into the economies of Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and other receiving cities, their fortunes diverged. Both groups found themselves ridiculed for their folk ways and accents and suffered backward assumptions about their abilities and intelligence. But with the stroke of a pen, many eastern and southern Europeans and their children could wipe away their ethnicities—and those limiting assumptions—by adopting Anglo-Saxon surnames and melting into the world of the more privileged native-born whites. In this way, generations of immigrant children could take their places without the burdens of an outsider ethnicity in a less enlightened era. Doris von Kappelhoff could become Doris Day, and Issur Danielovitch, the son of immigrants from Belarus, could become Kirk Douglas, meaning that his son could live life and pursue stardom as Michael Douglas instead of as Michael Danielovitch.

Ida Mae came to Chicago (Milwaukee first) in 1937.

Ida was about 22 when she and George left Chickasaw, Mississippi. They arrived in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Milwaukee was the other side of the world compared to the wide-open land of cotton fields. Most colored migrants were funneled into the lowest-paying, least desired jobs in the harshest industries – iron and steel foundries and slaughtering and meatpacking. Some companies “never did intend to employ Negroes.”

When George found it difficult finding a job in Milwaukee, he left for Chicago where his older brother lived.

Chicago

Timidly, we get off the train.

We hug our suitcases,

fearful of pickpockets…

We are very reserved,

for we have been warned not to act green…

We board our first Yankee streetcar

to go to a cousin’s home…

We have been told

we can sit where we please,

but we are still scared.

We cannot shake off three hundred years of fear

in three hours.

- Richard Wright, 12 million Black Voices

In Chicago, blacks were confined to the least desirable blocks. The conditions they lived in were sometimes horrible. “With several thousand black southerners arriving each month in receiving cities of the North and no extra rooms being made available for them, attics and cellars, store-rooms and basements, churches, sheds and warehouses,” wrote Abraham Epstein in his study of the early migrations, “were converted to contain all the new arrivals.

Then there were the Chicago riots beginning in 1919. A 17-year-old black swam across an imaginary line along Lake Michigan, that separated blacks and whites. Following the infraction, whites dragged black passengers from streetcars and beat them. Blacks stabbed a white peddler and laundryman to death. Over thirteen days, 38 people were killed, and 537 were injured.

Speaking about some many wonderous, sad, and unspeakable things in her life, and there being not enough time to tell all she witnessed, Ida Mae remarked, “[t]he half ain’t been told.”

Mississippi was deep inside her, but she gave no thought of ever living there again. Her home was where she planted herself, and that happened to be Chicago.

In the fall of 1977, Ida Mae’s family was chosen out of all of the families on the South Side to represent the typical Chicago family at Thanksgiving. Someone at the Jewel Food Stores knew of Ida Mae’s Mae family, and knew that they were good solid people, and Ida was beloved by everyone who came in contact with her. A camera crew showed up at Ida Mae’s three-flat home and produced a picture that ran as a full-page ad in the Chicago Metro News on Saturday November 26, 1977.

___________

“[Y]ou watch yourself now, grandma,” came a young drug dealer’s voice who knew Ida Mae’s comings and goings. She was familiar with the code names and street names of the pushers and hustlers. They respected Ida Mae. And, Ida Mae’s response to all of the activity beneath the windowsill of her one room-flat, was that she would pray for them.

To Bend in strange Winds

I was a southerner, and had the

map of Dixie on my tongue.

– Zora Neale Hurston, Dust tracks on the Road.

Newcomers like Ida Mae had to worry about acceptance or rejection not only from whites they encountered but from the colored people who arrived ahead of them, who could at times be the most sneeringly judgmental of all.

Migrants brought new life to the old receiving stations, but by their sheer numbers, they pressed down upon the colored people already there. It left the well-suited lawyers and teachers living next to sharecroppers in head scarfs just off Illinois Central. The middle-class coloreds searched for a way out. They tried to insulate themselves by moving to the gradually expanding South Side.

Like the German Jews who in the nineteenth century feared that the influx of other eastern European Jews would endanger their marginal foothold in gentile Chicago, and so were the same sentiments of the more established coloreds as acknowledged in the Chicago Defender. “Those who have been established in the North have a problem. “That problem is caring for the stranger within their gates.”

The Other Side of Jordan

We cannot escape our origins,

however hard we might try,

those origins contain the key

– could we but find it –

to all that we later become.

- James Baldwin, Notes of a Native Sun

Chicago was considered crucial to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s election in 1940. Precinct captains had passed out palm cards and flyers and tutored potential voters like Ida Mae. Ida Mae didn’t’ know what was at stake, but suddenly everyone around her was talking about something that she’d never heard of back in Mississippi – voting.

Back home, no one dared talk about such things. She couldn’t vote in Mississippi. She never knew where the polls were in Chickasaw County. If ever she had the nerve to attempt to vote, she would have been turned away for failing to pay a poll tax or answering questions such as how many grains of sand were there on the beach or interpret an obscure article in the Mississippi constitution.

On the day of voting, Ida Mae stepped inside of the voting booth for the first time in her life and drew the curtain behind her.

What was unthinkable in Mississippi would eventually become so much a part of life in Chicago that Ms. Tibbs, the precinct captain, would ask

Ida Mae casts her first Ida Mae to volunteer at the polls the next time.

vote, ever…

Ida Mae did not see herself as taking any kind of political stand. But in that simple gesture, she was defying the very heart of the southern caste system, and doing something she could not have dreamed of doing – in fact, had not allowed herself to contemplate – all those years in Mississippi.

Complications

What on earth was it, I mused,

bending my head to the wind,

that made us leave

the warm, mild weather of home

for all this cold,

and never to return,

if not for something worth hoping for?

- Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

George landed a job at the Campbell, one that he would hold for many years. Ida Mae, on the other hand, was having a time getting a job. Some employers started requiring voice test to weed out those from the South, tests that Mississippians just up from the plantation would have been all but assured of failing. There was one company, unapologetically, called for five hundred women, specifying that they be white. The husband of one couple let it be known that, in addition to house cleaning, he expected Ida Mae to sleep with him. Ida Mae completely rejected him and the work out of hand. She attempted assembly line work but found it too dangerous and quit soon after another colored woman got some of her fingers cut off. In time she would get a job at the Walther Memorial Hospital on the West Side of Chicago. With Ida Mae working, the family could move out of the one-room apartment into a flat for everyone.

The Prodigals

‘Sides, they can’t run us all out.

That land’s got more of our blood in it than theirs.

Not all us s’ posed to leave. Some of us got to stay,

so y’all have a place to come back to.

- A sharecropper who stayed in

North Carolina, From Marta

Golden, Long Distance Life

Migrants had gone off to a new world but were stilled tied to the other. The homesick migrants loaded up their sleepy children in the dark hours of the morning for the long drive to the mother country when there was death in the family or a love one needing tending or just to show off how well they were making out up north. When they saw the cold airs of the New World seeping onto their northern-bred children, they sent them south for the summer so the children would know where they came from.

Ida Mae did not go back often, not because she was afraid but because she had family to tend to in Chicago. She went back for illnesses and funerals -when her mother, Ms. Theenie, took ill and died and years later, when her baby sister, Talma, got sick and died. Her husband, George, went back only once – for the funeral of his brother, Willie, who had raised him.

Disillusionment

Let’s not fool ourselves.

we are far from the Promised Land,

both north and south.

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

In 1951, a colored bus driver and former army captain named Harvey Clark, and his wife, Johnetta, faced an impossible situation. It was the same dilemma that Ida Mae and her family and just about every household up from the South faced.

Harvey Clark was from Mississippi like Ida Mae and brought his family to Chicago in 1949 after serving in World War II. The Clarks lived in a one-room tenement. The husband and wife were college educated. The cramped quarters forced them to seek more space for their family. They finally found an apartment with five bedrooms and the cost only sixty dollars a month. The apartment was located in Cicero, an all-white town on the southwest border of Chicago, where Al Capone went to elude authorities during Prohibition.

On the move-in day, white protestors met them as they were unloading their truck. As the Clarks attempted to enter the building, the police stopped them at the door. The police took sides with the protestors and would not let them in. The Clarks were not to be deterred, they attempted again on July 11, 1951, to move in. More than one hundred Cicero protestors were at the property. The Clarks fled, and a mob stormed the apartment and threw furniture out of the third-floor window as the crowd cheered. In an hour the mob had destroyed what took nine years for the Clarks to accumulate. The next day a full-blown riot was underway. Then Governor Adlai Stevenson called out the National Guard. The riots attracted world-wide attention.

It was U.S. Attorney Otto Kerner whose job it was to prosecute the federal case against Cicero officials, who later under President Lyndon Baines Johnson, was appointed to investigate the disturbances of the 1960s. The report became known as the Kerner Commission. Its stark pronouncements concerning the country’s progress towards equality were invoked many times over: “our nation is moving toward two societies, one black and one white -separate and unequal.”

Revolutions

I can conceive of no Negro native of this country

who has not, by the age of puberty, been irreparably scarred

by the conditions of his life…

The wonder is not that so many are ruined

but that so many survived.

- James Baldwin, Notes of a Native Son

Dr. Martin Luther King came to Chicago in 1966 in his first attempt to bring the civil rights movement to the North. Ida Mae, could hear him from the loud speakers, and was taken in by the sheer presence of the man, who by then had already won the Nobel Peace Prize, led the March on Washington, witnessed the signing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and overseen his epic battles against Jim Crow in places like Selma and Montgomery.

King spoke: “Negroes have continued to flee from behind the Cotton Curtain,” he told a crowd at Buckingham Fountain near the Loop in Chicago, testing out a new theme in virgin territory, “But now they find that after years of indifference and exploitation, Chicago has not turned out to be the New Jerusalem.”

Blacks in the North could already vote and sit at a lunch counter or anywhere they wanted on an elevated train. Yet, they were hemmed in and isolated into overcrowded sections of the city – the South Side and the West Side -restricted to the jobs that they could hold and mortgages they could get, their children attending segregated and inferior schools, not by edict as in the South but by circumstances with the results pretty much the same.

Then Mayor Richard Daley promised Dr. King that he and supporters would be protected. Some four thousand residents gathered in advance to protest King’s presence. Members of the crowd cursed him with epithets from a knoll overlooking the march. Hecklers called King’s supporters cannibals, savages, and worse. Many in the crowd waived Confederate flags. Some wore Nazi-like helmets.

King later remarked about the protestors: “I have seen many demonstrations in the South.” But I have never seen anything so hostile and so hateful as I’ve seen here today.”

In the Spring 1967, Ida Mae, George and her children purchased a three-flat in what they believed to be a newly opened-up neighborhood in South Shore. Ida Mae liked the neighborhood. Weeks after Ida Mae and family moved in, she noticed that whites were moving out of the neighborhood in record numbers. By the end of the year, the 7500 block of Colfax and the rest of South Shore went from all white to nearly totally black. Stores closed and schools’ racial composition changed. Famed singer, Mahalia Jackson, was given warnings to move or her home would be bombed. The neighbor shot rifle bullets through her windows.

By the time the Great Migration had reached its conclusions, sociologists would have a name for that kind of hard-core racial division. They would call it hypersegregation, a kind of separation of the races that was so total and complete that blacks and whites rarely intersected outside of work.

In February 1968, orderlies and nurse’s aides of Walther Memorial Hospital went on strike for higher wages. Ida Mae had finally come into a job she liked and that suited her temperament. She had come a long way from the cotton fields of Mississippi for the chance to work indoors with people rather than outdoors with crops and to get paid for the job and feel some dignity doing it. The concept of not working a job one had agreed to do was alien to Ida Mae.

Ida Mae had not been schooled in the protocols of union organizing, but she knew that she could not afford to lose her job and couldn’t see how not working was going to help her keep it. She was under more pressure than ever. She and George had just bought their first house, the three-flat in South Shore, and had new and different bills coming at them than ever before – from the mortgage to the utilities, to property taxes and hazard insurance. Ida Mae’s pastors pleaded with her not to cross the picket line. Her children did not want her to go to work in defiance of the pickets. Ida Mae and her friend, Doris, decided that they would go to work. When management learned that she and Doris were coming to work, the hospital arranged for them to be picked up and escorted them into the building.

____________

Little would Ida Mae and George know that when they bought a home on Colfax Avenue in Chicago, their home was within a few blocks of where Michelle Obama (nee Robinson) was born, South Euclid Avenue. Nor would she have known that the State Senator she voted for in Chicago’s South Side and met at a ”beat” community meeting on August14, 1997, would become the first African American president of the United States.

Aftermath

Ida Mae put disappointments in a lockbox in the back of her mind and lived in the moment, which is all anybody has for sure. She had learned long ago when things were so much harder in the Old Country she left behind, that, after all she had been through, everyday

was a blessing and every breath she took a gift.

- Ida Mae’s legacy

Epilogue

Ida Mae had the humblest trappings but was perhaps he richest of them all. She had lived the hardest life, been giving the least education, seen the worst the South could hurl at her people, and did not let it break her. she lived longer in the North than in the South but never forsook her origins, never changed the person she was deep inside, never changed her accent, speaking as thick a Mississippi drawl in her nineties as the day she caught the train out of Okolona sixty-odd years before.

She was surrounded by the clipped speech of the North, the crime on the streets, the flight of white people from her neighborhood, but it was as if she was immune to it all. She took the best of what she saw in the North and in the South

Ida Mae’s faith and interwove them in a way she saw fit. Her success was spiritual, perhaps the sustained her. hardest of all to achieve. And because of that, she was the happiest and lived the longest of them all.

Afterword

Her husband, George, having predeceased her, Ida Mae Gladney died peacefully in September 2004. Her family was so distraught that her children and grandchildren kept her room precisely as it was for years. The door remained closed in memoriam to her, and no one had the heart or strength to touch it.

New York

A blue haze descended at night,

and, with it, strings of fairy lights

on the broad avenues…

What a city! What a world!…

The first danger I recognized…

was that Harlem would be

too wonderful for words.

Unless I was careful,

I would be thrilled into silence.

- Richard Wright, 12 Million Black Voices

George Swanson Starling came to New York April 15, 1945

He could see a blur of pedestrians brushing past him and yellow taxicabs swerving up Eighth Avenue, concrete mountains were obscuring the sky, steam rising from sewer grates, the Empire State Building piercing the clouds above granite-faced office buildings, and all around him, coffee shops and florists and shoe stores and street vendors and not a single colored-or-white only signs anywhere.

George would quicken his steps, learn to walk faster, hold his head up and his back stiff and straight, not waving to everyone whose eyes he met but instead acting like he, too, had already seen and heard it all, because in a way, in a life-and-death sort of way, he had.

Harlem had become majority black, its residents having built institutions like the Abyssinian Baptist Church, and regaling white audiences at the Cotton Club. The changeover from white to predominantly black was not a smooth one and went to the very heart of the basic difference between the North and South, between the authoritarian control over colored lives under Jim Crow and the laissez-faire passivity in the big, anonymous cities of the North and West.

Panicked white property owners drafted restrictive covenants in which they swore not to let colored people into their properties for fifteen years or “till when it was thought this situation… will have run its course.” Some covenants covered entire blocks and went so far as to limit the number of colored janitors, bellboys, butlers, maids, and cooks to be employed in a Harlem home or business. White leaders tried to segregate churches, restaurants, and theaters.

The flood of colored migrants soon broke down the last of racial levees in Harlem. The following is typical of the language of notices posted onsigns in a Harlem tenement in 1916:

“We have endeavored for some time to

avoid turning over this house to

colored tenants, but as a result of

rapid changes in conditions… this

issue has been forced upon us.”

George located a brownstone on 132nd street off Lenox in what people on Sugar Hill called the Valley, which accounted for most of which would be considered Harlem and was thought of as perfectly respectable, even admirable, for someone like George. Now that he had a place, he was in position to send for Inez.

The Draw of the South

No matter how settled the migrants got or how far away they ran, the South had a way of insinuating itself, reaching out across rivers and highways to pull them back when it chose. The South was a telegram away, the other end of a telephone call, a newspaper headline that others might skim over but that hurled them back to a world they could never fully leave.

In December 1951, George had been in New York for six years when the South came back to haunt him. He got word that something terrible had happened to Harry Moore, an old acquaintance of his.

Harry Moore was the chief organizer of the NAACP. There were two trials in Eustis, Florida which caused Harry to go on a quiet crusade to bring to the public’s attention to the inhumane treatment of blacks. One involved the torturing and drowning a young colored boy who sent a Christmas card to a white girl. The girl told her father. A posse of white men was responsible for killing the boy. The other matter involved allegations that four black men raped a white woman.

Harry began investigation both tragic events. Word had gotten back to the school board that Harry was stirring up trouble. The authorities later fired Harry Moore and banned him from ever teaching in Florida. Nonetheless, Harry continued investigating matters of coloreds being unfairly treated.

During Harry’s and his wife’s twenty-fifth wedding anniversary, a bomb exploded under the floorboards of their home. Harry died soon after the bombing and his wife succumbed eight days later. The investigation revealed that the Klan was responsible for the deaths, but no one was ever prosecuted.

George had met Harry Moore, school principal, in the 1940s. They had only met once, but both shared the outrage over the treatment of colored people when it came to schools. Again, it was Florida’s school boards, each its own fiefdom, had a habit of shutting down the colored schools, weeks or months before the school year was supposed to end, blaming the closures on budget shortfalls. White schools remained opened. Blacks’ salary was roughly one-half of whites’ salary.

J.S. Pinckney, principal of the colored school, expressed support for the cause; after all, he was being cheated by the pay gap too. Everyone in town knew how vocal George could be, and the principal nominated him to lead the registration drive. George said years later that he did not want to do it, but the principal assured him that he wouldn’t be going it alone.

George was sought because of his organizing skills. George was to convince teachers to join the NAACP which would give them strength in numbers. George could not sign up one teacher. George learned of the contradictions and the compromising positions. The principal had given the impression to colored people in town, that he was all for progress of the NAACP. But all the while he was undercutting the effort in private. The principal and his wife actually joined the NAACP. The principal told George he paid his membership fee, but not to put his name on the list. When approached by the white board, the principal told the board, that he told colored teachers if they joined the fight, he would fire them all.

__________

It seemed every night George saw violence come into his living room on his black-and-white grainy television. Images of colored teenagers standing up to southern sheriffs brought back memories when he was a young man again pressing against the barbed wall of the caste system in Florida. Several days later he was on the subway reading the newspaper and saw all these black people down on the ground and dogs jumping all over them and cops beating them in Alabama.

Something welled up in him. Everything raced before him: the cheating foreman in the groves, his running for his life, the hangings and burnings. The city seemed to be pressing down on him. His own children were being swallow up by the streets. once a bartender in the city smashed the glass after he finished his drink, rather than place it with everyone else’s glasses. George said he got so mad with the newspaper in front of his face, and when he looked up, he was face-to-face with a white man. He hadn’t seen the man before and certainly did not know him, but he was white. George said the hatred surged up in him. He was angry and wanted to hurt somebody.

The bombing deaths of four little girls just before Sunday church service in Birmingham Alabama, assassination of civil rights workers, black and white, Medgar Evers, the confrontation on the iconic Edmund Pettus bridge in Selma Alabama, weighed heavy on George. If those horrific incidences were not enough, in 1962, he learned that white supremist set fire to three churches in Georgia in an effort to deny blacks the right to vote. George collected money from whomever he could and sent money to the New York Amsterdam News, the black newspaper in New York, that was collecting funds to rebuild the churches. George said I wanted to help in the only way I know.

________

In 1964, President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act, barring segregation in public accommodations.

Most blacks did not know the full ramifications of the law and on the railroad were accustomed to ushering blacks to the Jim Crow car. Tradition was that when the train left the New York train station, blacks could sit in any car of their choice. When the train came to Union station in Washington, D.C.,

George’s life’s work for 35 years… no promotion blacks would have to remove themselves and their belongings to the Jim Crow car for the southern leg of the trip.

After the Civil Rights Act passed, George took it upon himself to let blacks know, that they no longer had to move once the train headed south. They had paid and reserved a seat of their choosing on the train. This was not easy because some blacks did not feel comfortable sitting in in integrated car. Some blacks move but others would not. To further complicate matters, the conductors on the train would never tell black passengers they could sit anywhere on the train. If effect, after the train from the north reached the Washington D.C., the conductor would routinely tell blacks they had to move to the Jim Crow car as they were required to prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

George had been the one to set the course of the lives of his children before they were born. The parts of the city black migrants could afford – Harlem, Bedford Stuyvesant, the Bronx – had been hard and forbidding places to raise children, especially for the trusting and untutored people from the small-town South. The migrants had been so relieved to have escaped Jim Crow that many had underestimated or dared not to think about the dangers in the big cities they were running to – the gangs, the guns, the drugs, the prostitution. They could not have fully anticipated the effects of all these things on children left unsupervised, parents off at work, no village of extended family to watch over them as might have been the case in the South.

George and Inez sent their daughter, Sonya, to Florida for the summer. She was thirteen at the time. The last thing they expected happened: she got pregnant. Around the same time Sonya became pregnant, so did another woman. It was a woman George had been seeing behind Inez’s back.

George’s daughter with a child and his son took to the streets in the world of drugs. It is ironic that George would be critical of blacks who expressed their blackness through the Afro hair styles. He referred to young blacks in an unflattering way: they were shacking up, they called it, in a flouting kind of way, even as tortured as his marriage had become, he couldn’t bring himself to do.

George had started going to church and found solace in that. He became a deacon of the church. The fact that George never completed college, gnawed at him for as long as he lived. George was never happy with Inez. He only married her to spite his father because his father would not finance the two remaining years of his college education. He often thought that had he never married Inez from the other side of the tracks, perhaps he could have obtained the education to fulfill his potential.

Aftermath

Lake County, Florida began to join the rest of the free world in the late 1960s and early 1970s, six decades into the Great Migration, when black children and white children, for the first time in county’s history, began sitting in the same buildings to learn their cursive and multiplication tables.

But trouble abounded in the county. Fights broke out between black and white students. Sheriff Willis McCall had acquired a reputation as a segregationist and white supremist in Lake County. One of the fights, Sheriff rode up with his dog and went after the black student without knowing who was at fault. McCall was accused in case after case of alleged abuse and misconduct against black people in the county. He would be investigated forty-nine times and survive every one of them.

When President Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, the only public building in the United States that refused to lower its flag to half-staff was McCall’s jail in Tavares, the Lake County seat.

Colored only and white only signs were coming down all over the South during the 1960s. But Sheriff McCall did not take down the colored waiting room sign in his office until September 1971, and then only after threat of a federal order. Later in 1972, McCall was indicted for second-degree murder for allegedly kicking a black prisoner to death. The prisoner was in jail for a twenty-six-dollar traffic fine. McCall was acquitted. McCall was defeated in the November election when blacks were able to vote and turned out in force to defeat him. Then too, a new generation of whites had entered the Florida electorate, the younger people who may have identified with the young freedom riders in Mississippi and Alabama even if they would not have participated themselves.

The defeated sheriff retreated to his ranch where he tended his citrus grove. He could take comfort in the fact that, for better or worse, Lake County would not soon forget him, and took pride in his role of protecting southern tradition.

The times may have changed but Sheriff McCall never would or sought to. Displayed in his home was this colored waiting room sign that once hung in his office and that he was forced to take down under threat of federal court order. Nobody in the world was going to tell him what he could do or what he could hang in his own home.

_________

There were scientific and medical explanations for what befell George’s wife, Inez. But those who knew her could see the storm whirling inside her – a thousand little heartaches since coming into this world and being hooked now into marriage born of adolescent love but mostly of spite. The one thing that she categorically loved was her first born, Gerard who broke her heart with his drug addiction.

Ida and George had lived with the fact that they were not happy and the marriage ended more sorrowfully than either of them could have ever imagined. Inez, after suffering under the weight of disappointments, the heartaches caught up with her and she succumbed and died of cancer in 1978.

Inez was gone, but George would not have good relations with his children. The thirty-five years he worked the railroad kept him away from his family – he was away too many days and nights. When George began working, it was an honor to be a porter at the time. But in reality, it was nothing but hard work. In the thirty-five years of employment with the railroad, he was never moved up or promoted.

__________

George had not totally left the South. He always had a soft spot in his heart for Eustis, Florida. He would come back for funerals and illnesses and the Cutwright Colored High School reunions. He was looked upon with a distant kind of respect. He was once one of them, but he chose a different path. When people would hear he is in town, they head over to Viola’s (the widow of his deceased stepbrother) bungalow and remove their hats before they walk in to see a prodigal son of Eustis.

Whenever George attended the local church, Gethsemane Baptist Church in Eustis, the choir would motion for him to come forward and sing a solo. George would remark, “needless to say, I am grateful to be in your midst. I look over and see my father, mother and my daughter (all of whom were now deceased) and it always make me a little full. So, if you see me become emotional, I hope you will understand.” He then sings a hymn, Without God I could do nothing…without him, I would fail. After the congregation claps, he takes his seat, takes his glasses off and wipes the tears from his eyes.

Epilogue

George Starling succeeded merely by not being lynched. Just living was an achievement. He managed to reach a level of material solvency he may never have known in the South, assuming he had survived. He paid a price. He enjoyed the fruits of the North and South but grieved over how he had to leave and what might have been. He was as northern as he was southern, bi-regional, one might say, not fully one or the other. His ultimate success was psychological freedom from the bonds of his origins, leaving the South and working the railroads gave him a view of the world he might otherwise never have had. He became a master observer of events. And in the end, the thing he wanted most of all, the education denied him early in life, came to him without his realizing it. He got an education, not the formal one of his dreams, but one he could not have imagined, a fuller one, perhaps, for having left the limited world of his birth.

Afterword

George, a diabetic died September 3, 1998. The family held two funeral services for him – one in Harlem and the other in Eustis, Florida.

Robert Joseph Pershing Foster came to California on April 6, 1953

Pershing’s mother, with pride, named her son after General John J. Pershing (“Black Jack”). Pershing was given command of the 6th Cavalry Regiment in the West, where he participated in the Apache and Sioux campaigns. He was promoted to first lieutenant of the 10th Cavalry Regiment in Montana, one of several segregated regiments formed after passage of an 1866 law authorizing the U.S. Army to form calvary and infantry regiments of black soldiers. Pershing expressed his admiration for black soldiers (aka “Buffalo Soldiers”), earning for himself the honorary nickname of “Black Jack.” In 1898, he went up San Juan Hill, Santiago, Cuba (Spanish – American War), with his black troopers, to support Cuba’s fight for its independence from Spain.

Pershing was starting over now. Pershing’s mother was gone. What he would call himself was up to him. He changed his name to Robert or Bob. He thought it was modern and hip, and it suited the new version of himself as the leading man in his own motion picture.

__________

In 1954, Alice and the children joined Robert in their walk-up apartment Robert had scrambled to secure for his family after the apartment he wanted mysteriously fell through. Robert and Alice had not lived together most of the twelve years of their marriage. Now that they were all together in Los Angeles, it hit them that they didn’t really know each other.

Robert and Alice had cultural difference over food and money. Alice who was brought up in the upper class in the South, wanted to wait until they purchased a house before she sought her socialite yearnings. From Atlanta, Alice’s mother had signed her up with the Links, perhaps the most elite of the invitation-only, class-and color-conscious colored women’s societies of the era. she did not want to activate her membership until they were in their home. She exclaimed, “we are not ready, Robert.”

In his quest to improve his status, Robert wanted to purchase a new Cadillac. Alice quipped, “You don’t have a garage to put it in. Robert won that argument when he brought the Cadillac home.

Robert was already plotting new ways to prove himself to the naysayers, black and white, in Louisiana and L.A. “My lifestyle ‘l blow ‘em outta the water,” Robert would say. “Just blow ‘em outta the water, ’cause I’ll go on and do what I wanna do.”

__________

Robert was always excited of the idea of going to Vegas. Through a friend he and twelve others, showed up at the Rivera Hotel to be turned away, claiming no reservations had been made for their party. Enraged and embarrassed, Robert called his friend who quickly made arrangements at the Sands hotel. Sands did not have enough rooms to accommodate them. Later, they were accommodated at the Flamingo Capri. Vegas, and all of its ambience and trappings, would later become a habit-forming distraction.

After struggling to build his practice among blacks both from Louisiana and L.A., in the mid to late 1950s, Robert finally became quite popular among blacks. Ray Charles would become a his patient and friend. In fact, Ray Charles included Robert in the lyrics of a song he had written. Ray Charles and his wife, Della Beatrice Robinson, would name their son after Robert. Robert had made it big. His patients would stand in long lines, waiting his or her turn to enter his office.

_________

Two famous cases, Shelly v. Kramer and Barrows v. Jackson, struck down restrictive covenants in Deeds. In spite of the courts having ruled restrictive covenants illegal, Robert did not want to integrate a new neighborhood. Robert wasn’t going to put himself through that. He found a safe place that suited him. Not only were black people there already, but they were among the finest and most socially connected in all old Los Angeles. The house was a white Spanish Revival, right next door to the most prominent architect in Los Angeles and maybe the country, Paul Williams.

Robert’s father – in – law, Rufus Clement and Robert, were at opposite ends of the Great Migration. They represented the two roads that stood before the majority of black people at the start of the century. One man had stayed in the South. One had left it behind. Both had worked long and hard and had all the material comforts most any American could dream of. Yet both men wanted to prove to the other and to everyone else that his was the wiser choice, his life the more meaningful one.

President Clement was the tight-buttoned scion of the southern black bourgeoisie. Robert was a brilliant but tortured free spirit who had run from the very strictures Clement stood for. Clement was a distinguished accommodationist in the Jim Crow South. He avoided the messy confrontations of the civil rights era.

Robert began spending more time with his patients, his bookies, and the B-list of musicians he liked to hang around with. He was drinking more and coming in late. He had fallen hard for Vegas and now had discovered horse racing. At one point, Alice had had enough, she packed up the girls and moved back to Atlanta with her parents. Somehow, Alice and Robert made up and she came back to Los Angeles. But nothing really changed.

In 1967, Dr. Clements died. After his death, Alice’s mother, Pearl, came to live with them. On December 8, 1974, Alice would die of cancer. Pearl could not take any more of Robert after her daughter’s death and left for Kentucky where her husband and daughter were buried.

Aftermath

The migrants were gradually absorbed

into the economic, social and political life of the city.

They have influenced and modified it.

The city has in turn, changed them.

-St. Clair Drake and Horace H. Cayton,

Black Metropolis

The Fosters had always had a complicated relationship with their hometown of Monroe – or rather, with the few other ambitious and educated black people maneuvering among themselves for the few spoils allowed them in a segregated world. As prominent as the Fosters had been, there would be no direct descendants living there by the 1970s.

Robert, a high roller, continued gamble. Robert was driving while drinking, had an accident and subsequently lost his license to drive. Robert would later suffer a heart attack. Reporting on his health condition, in 1997, Robert said, “ [T]he chest pain is growing more frequent [b]ut I am not going to have another operation. If anything happened to me tomorrow, I wouldn’t have any regrets. I have lived. I’ve done it all. The world don’t owe me nothing.” He was still gambling. His children and grandchildren appeared to be doing quite well.

On reflection, Robert remade himself in California and still does not fully know what to make of the place.

“It seemed like a fairyland the way they painted the picture, and I bought it. It’s not the oasis that I thought it was, but I got over that, too.”

Afterword

Robert Joseph Pershing Foster took his last breath on August 6, 1997. He was eight-eight years old.

Persons speaking at his funeral, said about him:

Robert’s gambling buddy, Romie Banks said, “Robert you have fought so many battles, been a champion for so many people. Was a perfectionist at everything he did, except winning at the racetrack.”

His son-in-law. Lee, spoke. “He let you know which way the wind was blowing,” whether you liked it or not.”

Easter Butler who met Robert at the racetrack declared simply, “Dr. Foster was one of the greatest men I ever knew.”

While gambling was Robert’s mistress, medicine was his beloved. The story of Robert Joseph Pershing Foster of Monroe, Louisiana and Los Angeles, did not end with his death. One story in particular came from a patient, Malissa Briley, on whom he had performed a surgery.

The surgery went well, but later that night, her blood pressure went out of control. She was on the verge of having a stroke, which could have killed her or left he her paralyzed. At midnight the hospital called Robert to report the turn of events. He rushed over right away. He tried to lower her blood pressure, but he couldn’t get it down either. The next morning, Briley awoke Dr. Foster, to see Robert in a chair by her bed.

caring… and

She was stunned to see him there. He was in his street clothes and uncharacteristically wrinkled. He hadn’t saved, had bags under his eyes.

She asked him, what are you doing here so early. He told her that she had gone through a crisis the night before and that neither he nor the hospital could get her blood pressure down. What did you do, she asked. “Well, I got to the point I couldn’t do nothing but pray,” he said. He had stayed by her hospital bed all night. Any patient he lost he took it personally and especially hard. He took it as a sign of his failure. So, he fought back sleep watching over this patient and praying for her to live. By morning her blood pressure had turn to a safe level.

Epilogue

Robert Foster found financial success and walked taller in a land more suited to him. But, he turned his back on the South and culture he sprang from. He rarely went back. He plunged himself fully into an alien world that only partly accepted him and went so far as to change his name and assume a different persona to fit in. It left him a rootless soul, cut off from the good things about the place he had left. He put distance between himself and his own children, hiding his southern, perhaps truest, self. He attempted to overcome his emigrant insecurities by trying to prove himself at casinos, proving instead how much one could lose in so short a time. In later life, he hungered for any news or reminder of home, like many an exile. He came obsessed with outward appearances as the city he fled to and nursed ancient wounds until the day he died. But it had been his choice, and he had lived the way he wanted.

________

The End – The Great Migration

In the end, it could be said that the common denominator for leaving the South was the desire to be free, like the Declaration of Independence, free to try out for most any job they pleased, play checkers with whomever they chose, sit where they wished on the street car, watch their children walk across a stage for the degree most of them didn’t have the chance to get.

The first black mayors in each of the major receiving cities of the North and West were not longtime northern native blacks, but participants or sons of the Great Migration. Carl Stokes, whose parents migrated from Georgia to Ohio would be elected in 1967 mayor of Cleveland, the first black to hold that position in any American city. Tom Bradley the son of sharecroppers, whose family fled central Texas to California when he was six years old, would become in 1973, the first black mayor of Los Angeles. Coleman Young, whose parents brought him north from Tuscaloosa Alabama, became mayor of Detroit in 1974. Harold Washington’s father migrated from Kentucky to Illinois, was elected mayor of Chicago in 1984. Wilson Goode, the son of sharecroppers from North Carolina, would become, in 1984, mayor of Philadelphia. David Dinkins, the son of a barber in Newport News, Virginia, would become mayor of New York in 1990. And Willie Brown, a one-time farm hand who left the cotton fields of east Texas for northern California, became mayor of San Francisco in 1996, after having served as the Speaker of the California Assembly, the first black to do so.

Over time the Migration would transform American music as we know it. The three most influential figures in jazz were all children of the Great Migration. Miles Davis’s family migrated from Arkansas. Thelonious Monk migrated with his family from North Carolina when he was five. John Coltrane left High Point North Carolina for Philadelphia in 1943.

Questions and Topics for Discussion (Penguin Random House Reading Guide)

1. The Warmth of Other Suns combines a sweeping historical perspective with vivid intimate portraits of three individuals: Ida Mae Gladney, George Swanson Starling, and Robert Pershing Foster. What is the value of this dual focus, of shifting between the panoramic and the close-up? In what ways are Ida Mae Gladney, George Starling, and Robert Foster representative of the millions of other migrants who journeyed from South to North?

2. In many ways The Warmth of Other Suns seeks to tell a new story—about the Great Migration of southern blacks to the north—and to set the record straight about the true significance of that migration. What are the most surprising revelations in the book? What misconceptions does Wilkerson dispel?

3. What were the major economic, social, and historical forces that sparked the Great Migration? Why did blacks leave in such great numbers from 1915 to 1970?

4. What motivated Ida Mae Gladney, George Starling, and Robert Foster to leave the South? What circumstances and inner drives prompted them to undertake such a difficult and dangerous journey? What would likely have been their fates if they had remained in the South? In what ways did living in the North free them?

5. How did the Great Migration change not only the North but also the South? How did the South respond to the mass exodus of cheap black labor?

6. At a neighborhood watch meeting in Chicago’s South Shore, Ida Mae listens to a young state senator named Barack Obama. In what ways is Obama’s presidency an indirect result of the Great Migration?

7. Wilkerson writes of her three subjects that “Ida Mae Gladney had the humblest trappings but was perhaps the richest of them all. She had lived the hardest life, been given the least education, seen the worst the South could hurl at her people, and did not let it break her . . . . Her success was spiritual, perhaps the hardest of all to achieve. And because of that, she was the happiest and lived the longest of them all” (p. 532). What attributes allowed Ida Mae Gladney to achieve this happiness and longevity? In what sense might her life, and the lives of George Starling and Robert Foster as well, serve as models for how to persevere and overcome tremendous difficulties?

8. What were the most horrifying conditions of Jim Crow South? What instances of racial terrorism stand out most strongly in the book? What daily injustices and humiliations did blacks have to face there?

9. In what ways was the Great Migration of southern blacks similar to other historical migrations? In what important ways was it unique?

11. Wilkerson quotes Black Boy in which Richard Wright wrote, on arriving in the North: “I had fled one insecurity and embraced another” (p. 242). What unique challenges did black migrants face in the North? How did these challenges affect the lives of Ida Mae Gladney, George Starling, and Robert Foster?

12. What motivated Ida Mae Gladney, George Starling, and Robert Foster to leave the South? What circumstances and inner drives prompted them to undertake such a difficult and dangerous journey? What would likely have been their fates if they had remained in the South? In what ways did living in the North free them?

13. Near the end of the book, Wilkerson asks: “With all that grew out of the mass movement of people, did the Great Migration achieve the aim of those who willed it? Were the people who left the South—and their families—better off for having done so? Was the loss of what they left behind worth what confronted them in the anonymous cities they fled to?” (p. 12. 528). How does Wilkerson answer these questions?

14. In what ways are current attitudes toward Mexican Americans similar to attitudes toward African Americans expressed by Northerners in The Warmth of Other Suns? For example, the ways working-class Northerners felt that Southern blacks were stealing their jobs.

15. In what ways are current attitudes toward Mexican Americans similar to attitudes toward African Americans expressed by Northerners in The Warmth of Other Suns? For example, the ways working-class Northerners felt that Southern blacks were stealing their jobs.

16. What is the value of Wilkerson basing her research primarily on firsthand, eyewitness accounts, gathered through extensive interviews, of this historical period?

17. After being viciously attacked by a mob in Cicero, a suburb of Chicago, Martin Luther King, Jr. said: “I have seen many demonstrations in the South, but I have never seen anything so hostile and so hateful as I’ve seen here today.” Why were northern working-class whites so hostile to black migrants?