The Man Who Brought Nonviolence to the Civil Rights Movement

The Last Speech

Dr. King collapsed onto the second story concrete walkway of Memphis’ Lorraine Motel.

A single shot from a lone assassin felled America’s greatest champion of social justice, not only for Blacks but for all disinherited peoples.

Martin Luther King, together with several associates were overnighting at the Lorraine Motel in the midst of their work with the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike.

The night before Martin had spoken at Mason Temple before hundreds of people. His speech that night may have been his greatest. Outside the auditorium, a thunderstorm howled. It blew open and shut ventilation shutters. Each time the shutters clapped gunshot-like shut, Dr. King winced.

King wasn’t feeling well. He was feverish and nursed a sore throat. He hadn’t prepared a talk, but as a seasoned orator, some of his best speeches were extemporaneous.

A single shot from a lone assassin felled America’s greatest champion of social justice, not only for Blacks but for all disinherited peoples.

His words that night carried the audience far from Memphis and the garbage worker’s strike. Dr. King surveyed his entire life. He dared to speak of his own impending death. Ten years before, he nearly died in Harlem. Since then, death-threats were a part of his life. He knew what it meant to be afraid.

Nevertheless, Martin spoke clearly of his intention to press on. He spoke of his commitment to non-violence. The question now, he insisted, was not between non-violence and violence. The choice was between nonviolence and non-existence.

As the speech spooled up, Martin laced it with biblical phrases.

I don’t know what will happen now; we’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop…Like anybody, I would like to live a long life—longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will…And I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. And so I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

The crowd leaped to its feet as Martin, out of energy, turned from the rostrum and collapsed into Ralph Abernathy‘s arms.

The next day he collapsed for the last time.

How Does Society Change?

As news of Dr. King’s assassination spread, violence erupted in American cities. Black leaders, like Bobby Rush, then a member of the militant Black Panthers, hoped that peaceful resistance was gone forever. He was convinced that Black liberation would move forward only when his people would meet violence with violence.

Elijah Muhammad, founder of the Nation of Islam and his more militant successor, Malcolm X, had given up on a racially mixed America. Their vision called for Blacks to withdraw into a self-reliant, Islamic society. The riots, which broke out in Los Angeles’ Watts neighborhood, were a good indicator of the simmering rage in American cities. African-Americans were angry and ready to act.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s saw something different for his people. An American Baptist minister, Martin understood the Christian life as essentially revolutionary. Under King’s direction, the marches, sit-ins, and demonstrations had the flavor of Jesus’ most radical prescriptions for personal conduct, notably praying for enemies, turning the other cheek, and letting all action arise out of love. Some Church historians have called King’s efforts the last great Christian ecumenical movement because Clergy from all denominations recognized their highest values in King and the linked arms with him.

One of Martin’s books was titled Strength to Love. Indeed it took remarkable perseverance to continue nonviolently, through the 1960’s, pressing for equality. Every demonstration was answered with dogs, fire hoses, and police batons. From Rosa Park’s 1955 refusal to give up her bus seat to a White man, to the Greensboro lunch counter sit-in, and now the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ strike, Martin Luther King’s philosophy had proven peaceful resistance’s power to rise above injustice.

The question is how did Martin become the champion of peace over violence, courage over fear; truthfulness over deception; and preeminently, love above all?

The Boy on the Train Platform

That story begins on a train platform in Daytona, Florida. The year was 1916, and a lonely boy is sitting on the ground, head between his knees, crying. Next to him is a beat up trunk and in his hand is a train ticket.

The boy’s name was Howard Thurman.

That ticket was the most valuable thing he had ever held. To purchase it the boy’s mother borrowed from her life insurance policy. That ticket would buy a train ride to Jacksonville, Florida where Howard would live with a cousin and attend high school.

Tears began to stream down the boy’s face and he buried his head in his arms

Daytona Beach provided no education for Black children beyond the seventh grade, not even exceptionally bright students like Howard Thurman who was the lead student as he finished seventh grade. A Baptist high school in Jacksonville had accepted him on the condition that he could get there and find a place to live.

It looked like getting there was out of the question. The man in the ticket booth had just told the boy that his battered trunk needed to be shipped “railroad express,” which cost extra. Howard Thurman had no money.

Tears began to stream down the boy’s face and he buried his head in his arms.

Moments later, Howard was startled to see inches from him a pair of work boots belonging to an old Black man in overalls and a denim cap. The man went to the ticket window, paid the baggage fee, and handed Howard the receipt. He disappeared.

From that moment, Howard Thurman’s journey began to roll forward, not only towards academic success but also a world-changing ministry.

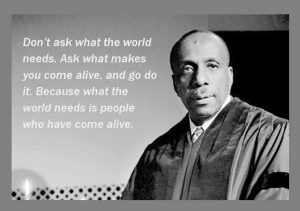

The Reverend Doctor Howard Thurman

After his high school years in Jacksonville, Atlanta’s Morehouse College admitted Thurman. While in Atlanta, Howard Thurman wrote award-winning poetry, preached in various pulpits, joined the debating team, became the dean’s assistant, and went to Cleveland, Ohio to sit in the public library and study philosophy. He still managed to be his class’s top student and in at the 1923 Commencement Exercises gave the valedictory address.

Thurman could feel in nature’s grandeur a window on own his immersion in life’s mysteries.

Howard Thurman’s tireless work and multiple projects while in college was just the start of a dazzlingly productive life. Each day brought a new project, a new city, a new publication.

In May of 1926, Howard Thurman graduated from Rochester Theological Seminary. Days later he traveled to LaGrange, Georgia to marry Katie Kelley in her home church. Days after their wedding, Howard and Katie launched their first pastorate in Oberlin, Ohio. The Mount Zion Baptist Church in Oberlin was only able to hold its brilliant young pastor for two years. Thurman has already started his life of incessant travel, speaking, and publishing. By 1932 he was a full professor of Christian Theology and Howard University’s Dean of Rankin Chapel.

Howard Thurman’s questing character also had a reflective side. Throughout his life, he was fascinated by huge natural marvels like giant trees or storms over the ocean. Thurman could feel in nature’s grandeur a window on own his immersion in life’s mysteries.

Thurman’s writings and sermons fearlessly spoke of the irreducible worth of a human being and the overall course of a person’s life. Thurman prayed and acted on guidance that came from his prayers. He read Quaker mystic Rufus Jones’ writings and insisted on meeting with him. Some of Thurman’s books were clearly mystical: Disciplines of the Spirit, The Inward Journey, and The Centering Moment.

India

As Howard Thurman rose in stature as a Black Intellectual he also was swept into the Black Internationalist movement. The African American civil rights struggle shared common elements with anti-colonial movements around the world and in the early 20th century these movements began talking with one another.

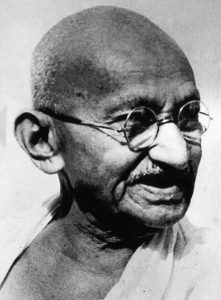

Mahatma Gandhi, who through nonviolent resistance, led India to independence from the British Empire had read Thoreau’s, Civil Disobedience, the four Gospels, the history of the American abolitionist movement, and the works of Booker T. Washington. American missionaries carried the spirit of India’s independence struggle back to the United States.

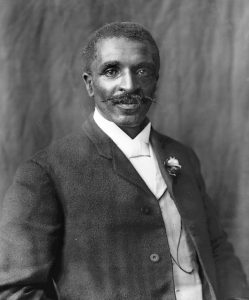

In 1929, George Washington Carver opened a fresh path to India, one which Howard Thurman was to take six years later. A brilliant botanist, George Washington Carver went to India to share new varieties of cotton seeds, peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes. Carver had developed these to boost harvests on land tilled by Blacks in the American South. Carver’s seeds and commitment to struggling people were transferable to the situation on the Indian sub-continent, which was in the midst of its own struggle with British White Supremacy.

Gandhi and Carver were natural allies. Gandhi’s liberationist philosophy worked to strengthen peasants struggling to cast off political oppression. They needed to be well-fed, self-reliant, and energetic. The Carver-Gandhi collaboration launched a fresh start for meetings between American Black intellectuals and Indian resistance leaders.

The Pilgrimage of Friendship

The merger of mysticism and cosmopolitanism in Howard Thurman’s personality propelled him to follow Carver in 1935 to India where he was both shaken up spiritually and inspired to develop the love-based philosophy that was to become the soul of the American Civil Rights Movement. Thurman led a delegation of four to India in 1935. This effort was called the “Pilgrimage of Friendship”

Thurman wanted to meet directly with Gandhi but had to bide his time for over four months awaiting an invitation to Gandhi’s rustic retreat. Howard Thurman realized, during this first phase of the trip as he traveled and spoke in Indian cities, that the Indian people were sympathetic to American Blacks’ dilemma.

For Thurman, the Pilgrimage of Friendship was an uncomfortable experience. Even though he was welcomed warmly everywhere he visited, freedom activists throughout India were suspicious of Thurman’s Christian faith.

His hosts criticized him in spirited debates for embracing the faith of the slave owners and lynching parties. One man accused Thurman, in the course of a five-hour debate, of being “a traitor to all the darker peoples on earth.” The distinguished American clergyman felt weak in answering his critics. Indeed, why would he embrace the very faith that had been a tool of his people’s subjugation?

Howard Thurman eventually met with Gandhi, but not before he was confused in an unforeseen spiritual crisis. Was his faith in Christ part of his peoples’ oppression or their liberation? The conversations with Gandhi in his mountain retreat spanned the final two weeks of the four-month pilgrimage.

In his autobiography, Thurman said Gandhi put him through the most demanding theological examination of his life. Both men held in highest esteem Jesus’ teachings. But as Thurman traveled home he carried with him a question that would haunt him for years. How could those teachings be the foundation of lasting liberation in the United States?

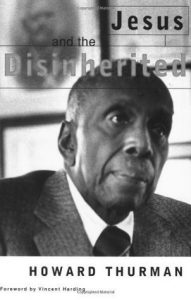

The “Pilgrimage of Friendship” shook up Howard Thurman and set him on a fourteen-year path of questioning that was finally resolved with the writing of his greatest book, Jesus and the Disinherited. More significantly, those months in India had deep consequences for America’s growing civil rights struggle.

The Book

The problem Howard Thurman sets out to solve in Jesus and the Disinherited is to restore Christianity as liberating way of life for all people—especially those whose “backs are against the wall.” As with wealth, status, social clout, and so on, Whites monopolize religion and bend it to serve their interests. In India, Thurman awakened to the White domination of his own faith. For years after, Howard Thurman wrestled with this problem, writing sermons and papers which served as preliminary studies in the answer he reaches in Jesus and the Disinherited.

His book’s primary insight is that Jesus himself assumes the social condition of the poor. Thurman isolates Jesus from his place in the New Testament and the Church. Like popping the largest jewel out of a crown and holding it up to light, Thurman sets aside abstractions like Christianity or the Bible and ponders Jesus alone. Poverty not only pervades Jesus’ life but also the life of his people, Israel. The Roman Empire’s subjugation of Jesus’ nation, leaving it with its back against the wall, means that Jesus earthly existence was doubly poor.

His book’s primary insight is that Jesus himself assumes the social condition of the poor. Thurman isolates Jesus from his place in the New Testament and the Church. Like popping the largest jewel out of a crown and holding it up to light, Thurman sets aside abstractions like Christianity or the Bible and ponders Jesus alone. Poverty not only pervades Jesus’ life but also the life of his people, Israel. The Roman Empire’s subjugation of Jesus’ nation, leaving it with its back against the wall, means that Jesus earthly existence was doubly poor.

Thurman’s consideration of Jesus alone, extracted from the New Testament’s pages, is exhilarating and probably controversial. He tells a story from his childhood that amplifies the boldness of his approach. As a boy, Howard would read from the Bible to his non-reading grandmother, who had been a slave and set free by the Emancipation Proclamation. She disallowed her grandson to read from Paul’s Epistles. Paul was socially elite. He was educated, enjoyed status as a Pharisee, and was a Roman Citizen. Thurman’s grandmother could feel Paul’s elitism through his words. And she rejected them. With Jesus, she could feel commonality.

The bulk of Jesus and the Disinherited considers three traps, which can ensnare the poor:

- fear

- deception

- hatred

Fear is the pervasive emotion for any person or group that is controlled by another group. What do you do when you’re constantly afraid as are African Americans who must deal with the slave master, the boss, the police, and daily reminders of their second-class status. A hidden consequence of living as the object of oppression is reduced self-worth. People with their backs against the wall feel poorly about themselves.

Thurman reminds his reader that Jesus faced oppression, the fear that went with it, the erosion of self-respect, and the perplexity over what to do about it. When Jesus speaks about the Father marking the sparrow’s fall and numbering the hairs on our heads, he is speaking as one with authority, to the low status of those who are subjugated. When Jesus is seen as sharing a condition common to all who are poor, suddenly his words are piercing.

When Jesus is seen as sharing a condition common to all who are poor, suddenly his words are piercing.

Deception similarly pulls on those who struggle. Lying and cheating round the sharp edges of a life beset by overweening authority. Life on the streets appears intolerably hard if you can’t take the shortcuts of lying to the caseworker, selling the food coupons for cash to fix the car, bending the chain link fence to get into the high school gym for basketball. Jesus too was tempted to sneak and lie but chose to live in radical truthfulness, whatever the result. “Let your ‘yes’ be ‘ yes’ and your ‘no’ be ‘no,'” suddenly is a daunting challenge. The follower of Jesus looking to be free is courageously plain-spoken.

Thurman’s argument reaches its zenith with his chapter on hatred. When overlords keep pressing people down, as African Americans have been oppressed, they, of course, burn with anger. Given an opportunity, they may strike back as did slaves in Virginia under Nate Turner. Hatred doesn’t seem like such an odious emotion when a person is being treated violently. In fact, hatred supplies energy to strike back and feels justified as a response to brutality by those in control.

Thurman cites Jesus’ best known and most distinct teachings about turning the other cheek and loving enemies as responses to the temptation to hate. The reason for loving enemies is because this response preserves the humanity both of the enemy and in the person with back against the wall. As Howard Thurman considered freshly Jesus’ teachings he noticed how much practicing them elevated the activist as well as the overlord.

Two Other Approaches to Social Change

It is useful to contrast Howard Thurman’s presentation of Jesus’ program with that of revolutionary economist, Karl Marx; or the American Community Organizer, Saul Alinsky.

The Marxist revolutionary’s worldview anticipates an unavoidable clash, usually violent, between the privileged and working class. The individual is minimized in an inevitable and righteous proletariat uprising. Personal character development is a nicety that might only get in the way of the will of angry masses.

Saul Alinsky, the union organizer who worked within the American system, called for a light version of socialist revolution. Instead of taking up arms, exploited people simply did disagreeable stunts to get the attention of elites who would capitulate in the face of inconvenience or acute annoyance.

When two people can stand together as peers, setting aside differences in their backgrounds, any class structure that had once permitted one of them to crush the other, fades away.

In Howard Thurman’s hands, Jesus’ revolution is at once a revolution in society and a revolution of the character.

In Jesus and the Disinherited’s final pages, Thurman speaks about the disciple who refuses to withdraw with fellow sufferers in their own protective enclave. Instead, the disciple ventures across separating boundaries to talk with the oppressor, not as one of the elite, but as a human being.

When two people can stand together as peers, setting aside differences in their backgrounds, any class structure that had once permitted one of them to crush the other, fades away.

Thurman set down his pen having at last resolved the crisis that began in India. He agreed to have it, which he called at the time, “The Religion of Jesus and the Disinherited,” published in a volume of essays titled In Defense of Democracy, edited by Thomas Herbert Johnson.

Howard and Martin at Boston University

In 1953, Howard Thurman became the Dean of Marsh Chapel at Boston University, where Martin Luther King Jr. was a doctoral student. King was immediately drawn to the new minister on campus and listened carefully to his sermons.

More of an activist than Thurman, Martin Luther King’s prominence in the growing Civil Rights Movement increased through the 1950’s. But Martin was never to forget Howard Thurman. In 1955 Martin Luther King Jr. joined Ralph Abernathy and Rosa Parks in leading the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the first nationwide mass civil rights demonstration.

During that exciting time, Martin Luther King carried a dog-eared copy of Jesus and the Disinherited. He had read the book so many times that the pages would slip out.

The Meeting in a Hospital Room

In 1957, Martin wrote, Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story. The following year, as he sat in a Harlem bookstore signing copies of his book, a crazed woman thrust a letter-opener into Martin’s chest, barely missing his heart.

Martin was rushed to the hospital where he nearly died.

In Boston, Howard Thurman saw the newspaper story of Martin’s hospitalization. He let the newspaper crumple on his lap, closed his eyes, and drew a long breath. God had kept Martin on Howard’s mind and now the young leader was lying on a hospital bed.

Later that day, Howard Thurman told his wife, Sue, that he was going to take the entire following day to drive to New York City to spend a few minutes with Martin Luther King Jr.

The nurse had cranked up the upper half of the bed and neatened the sheets.

Martin thought a long time about what his old teacher had said. Finally he responded, “So many people expect so much from me. I really believe that our hour has come.”

Howard nodded in agreement. Then he said, “Make sure you’re on the path that the Lord has appointed for you, Martin. If this is your hour, he’ll light your way. And he’ll hold you tight.”

Martin looked down at the folded bed sheets and nodded almost imperceptivity.

Thurman went on. “The movement excites me too. But I want you to pay attention to you. Who are you, Martin? If God has made you for this moment then he knows what you will do next…where you go from here as you wrote in the last chapter of your book.”

Few men could talk to Martin this way. Thurman’s words were sinking deeply into the young leader. “Will you do this for yourself? I’d like to ask you to take a minimum of four weeks beyond what these doctors prescribe for your recovery, and observe a season of stillness before God with your heart open to what he wants for you?” Will you do that Martin?”

Both men were silent for a long time.

At length, the venerable older preacher stood and offered a perfunctory prayer and walked out of the room.

Martin Luther King Jr. did what Thurman had asked. Except for the homilies preached at the Dexter Baptist Church, he stayed at home. He recovered. He read. He reflected. And he turned down every request to give speeches or travel.

At the end of those weeks of uncharacteristic quiet, Martin Luther King took a trip to India.

The Civil Rights Movement

The ten tumultuous years that followed that conversation were exhilarating and depressing. The Greensboro Lunch Counter protest sparked similar sit-ins in multiple states. Martin Luther King Jr. brought the massive march on Washington to a ringing close with his “I Have a Dream” speech. The movement was met with fire hoses, police batons, and dogs. Malcolm X was shot. President Johnson signed two Civil Rights Acts.

Then came that speech on a rainy night in Memphis.

Howard Thurman’s spirit was in the room.

Tired, stressed by years of death threats, Martin’s voice was nevertheless confident. That quivering baritone carried the crowd up the mountain where the Promised Land could be seen spread out before them. (Deuteronomy 34.1-8) That voice also dared to talk of death. Martin spoke candidly about his own near-death crisis when he had been stabbed.

Death was in the room. Racism was in the room. The exhilaration of how far they had all come was in the room. Howard Thurman’s spirit was in the room.

Like Moses before him, Martin knew that the race he had run had not been in vain.

And now at the end, Martin gave to his people all he had left. With eyes blinking and filled with tears, he ended with these words: “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

On that stormy night in Memphis, everybody who heard Dr. King saw that glory.