Reflections on David Bentley Hart’s THAT ALL SHALL BE SAVED

Here’s my personal big lesson in reading David Bentley Hart’s, That All Shall be Saved: If you take Hell out of your personal idea of Christian faith, everything else arranges itself around one grand drama of God bringing all things to their full beauty, truth, and goodness. And this is the single exquisite goal of this book: getting rid of Hell.

What Exactly is Hell?

By Hell, Hart means everlasting torture or everlasting death. The important word is everlasting. There are other hellish words and situations in the Bible. For example, Jesus appears to say hell in English translation in a couple of places in the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke). But he doesn’t use the word hell. Instead, Jesus uses a place name, Gehenna. Translators of the Bible have tended to render the word Gehenna into hell.

So, Jesus, speaking to disciples in Matthew and Mark about the importance of renunciation in the spiritual life, says, “Better to cut off your sinful hand than to enter Gehenna with two hands.” Obviously, Jesus is speaking in a hyperbolic way here. He’s exaggerating the necessity of cutting off one’s hand or plucking out one’s eye in order to press upon his disciples the importance of refraining from certain practices. Christians through the ages have understood this. I know of no Christian tradition that has literally practiced hand amputations.

The last part of Jesus’ sentence is equally an exaggeration. Accordingly, it seems sensible to understand Gehenna, another word in that sentence, in a metaphoric way. We exaggerate for effect all the time, which is an exaggeration. We die of embarrassment. Or, when lunch is late we’re starving.

Come to think about it, hell has always been a favorite metaphor, even today. Jesus speaks of the “gates of hell” (Hades in the Greek) not prevailing against the Church. Or we “march into hell for a heavenly cause.” Hell lends itself to verbal flourishes. And Jesus employs this in his teaching.

If I’m not the right track, if David Bently Hart is on the right track, then the infrequent references to hell or everlasting damnation in the Bible become even less frequent. Readers can judge for themselves by consulting the charts below.

Different Kinds of Hell

There are differing words and ideas that can fall under the English word hell. We’ve mentioned Hades (Sheol in Hebrew.) In one place the New Testament mentions a place similar to Hades, Tartarus. All three of these place names are underworld abode for the dead. Sheol has little to do with rewards and punishments for behavior in this life. Hades is best known as a Greek god and holding place for dead people. The word has crept into the Bible and is sometimes translated into English as hell.

The Hell to which Hart is devoting his considerable logical energies is mostly the product of church history. This monstrously evil place has swirled around in Christian theology, mostly in the west, and has served to distract believers from the absolute and final goodness of God and God’s plan for Creation.

There is an exquisite Greek word that appears only one time in the whole of the Bible and only once in Hart’s book. The word is apokatastasis, (Acts 3.21). It means the “restoration of all things.” Hart argues for such a restoration, which would include the saving of animals, the created world, and even Satan. He says as much:

Christians dare not doubt the salvation of all, and that any understanding of what God accomplished in Christ that does not include the assurance of a final apokatastasis in which all things created are redeemed and joined to God is ultimately entirely incoherent and unworthy of rational faith.[i]

Such restoration is the logical consequence of eliminating Hell as a factor in one’s Christian faith. No one is going to be banished to screaming suffering that never ends. God didn’t create such a condition for a segment of humanity. Neither is there a possibility that recalcitrant sinners, with all their faculties intact, can opt into such a fate.

The Simplicity of Hart’s Approach

Hart uses two tactics to make his case.

- First, he argues logically showing that eternal suffering is inconsistent with what we know about God or human beings.

- Second, Hart shows how quiet the Bible is about Hell.

He might have made the point that not all Christians through history have believed in Hell or Hell’s finality. But this point would not be too convincing since most Christians, influenced by Augustine, and later Aquinas and Calvin, have retained some degree of belief in a hellish destiny for at least some portion of humanity. This is not the case for Eastern Churches, the tradition to which Hart belongs.

Snarky Theology

Reading this book was quite fun. Hart has a nimble writing style and an extensive vocabulary. which equip him to make his points with devastating and entertaining precision.

He freely admits, in his entertaining opening pages, that most Christians do not believe what he is arguing, nor will they be convinced by the book. Hart insists that this inevitable opposition gives him license to dispense with intellectual niceties. He won’t in this book be paying the usual courtesies to opponents’ arguments.

Neither will he be falsely modest about setting forth his conclusions. There reader will not have to endure, “This is how I see it, but I may be wrong and always need to humbly be consulting the evidence and listening to my critics.” Hart states baldly that he is certain that he is correct and will waste no time with niceties.

He is, or at least he says he is, equally certain that most Christian traditions have held that Hell is part of the Christian picture. These opponents will hold on to this belief despite its absurdity, which will be laid out in the book. Hart goes on in effect: “I’m going to lose this argument so I’m really going to let it rip.”

Hart’s bravado both entertains and serves as a sly strategy to soften up his readers who feel the current growing interest in Universalism.

My first good laugh came early in the book with this complaint about dim-witted readers who would ask off-point questions at social gatherings:

The only good thing I can report about this is that I seem to have nearly perfected a tone of voice that veils vexation behind lustrous clouds of disingenuous patience; and the acquisition of a new social skill is always a blessing. But otherwise, to tell the truth, this is just the sort of conversation that makes the pleasure of even the most charming soiree begin to pall; I mean, really, how many times can one say, “I’m sorry, you’ve mistaken me for someone else” before the siren song of the cocktail-shaker across the room becomes irresistible…[ii]

To be able to laugh through a book that undertakes the a topic of utmost gravity, namely banishing Hell from one’s personal creed was an unexpected grace. Hart does all of this in a slightly snarky way. And in the end he lifts up the best imaginable outcome for the whole of Creation, which of course is the hope that, indeed God will save all. What’s more is that Hart does this from the stance of one of evident orthodox faith. The snark isn’t from the stance of one who doubts the glory of Christian faith, but from one who embraces it passionately.

Animals

I read That All Shall Be Saved as part of my preparation to teach a class on God’s design for animals. I’m learning that it is easier to make a biblical case that all animals, and the whole living world, (universality) will be saved than it is to say the same thing about people (universalism).

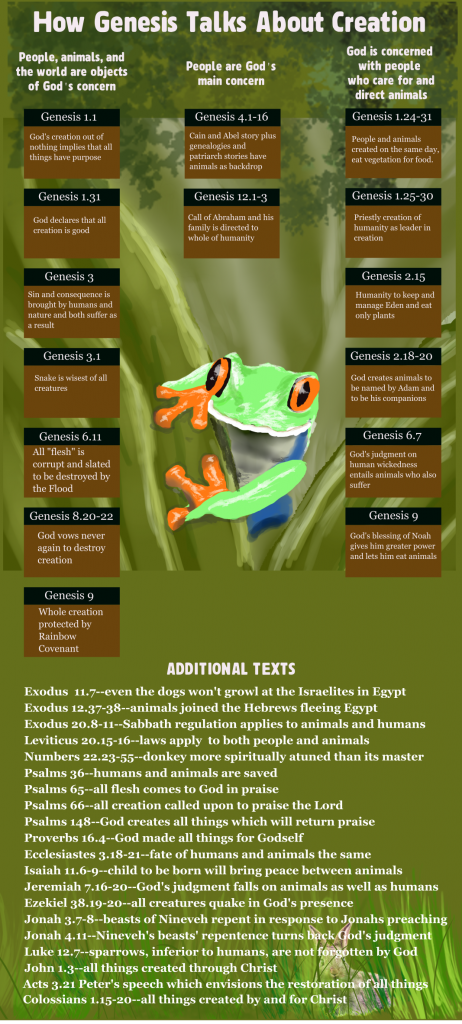

This is why I read this book. I’ve learned, mostly from David Clough’s two volume systematic theology on animals, that the non-human animals have an important role in God’s ultimate plan. We can easily see in the Biblical text this vocation and destiny for animals. This comes as a happy surprise to me. And what convinces me is that the Bible, mostly in Genesis, is surprisingly clear about this. (see the chart below)

The reader may wonder why church teaching hasn’t simply proclaimed that the divine plan of redemption will in the end save all things? The reason is that both the Old and the New Testaments present the scope of salvation in two or three not easily harmonized threads. For example, there are at least 23 New Testament passages where the text says plainly that God will save all that God has made. God will gather up in his love and bring to perfection all things—including the pets and wild animals. “For God so loved the cosmos that he gave his only son…” John 3.16

But the Bible doesn’t make this easy. In other places, one gets the impression that the plan of salvation will leave out some parts of creation or some people. In the Parable of the Bridesmaids (Matthew 25), the door to salvation? slams in the faces of some people. I’m working these days to review the entire Bible for statements on who and what gets saved and who or what doesn’t.

Hart does some of this work, especially in the New Testament and I developed two charts from his scripture lists in his Second Meditation which is a reflection on biblical eschatology. What about the Old Testament? People unfamiliar with the Old Testament might think that Hell would haunt every page of the Old Testament. In fact, Hell is almost entirely absent from the thought life of the Old Testament. Hell does appear once in Daniel 12.2. Daniel is a very late document in the Old Testament, a fact that might explain why this concept of eternal punishment crept into his thinking–if in fact it did.

Universalism in the New Testament

| Chapter and Verse | English Translation of the Text |

| Romans 5.18-19 | So, then, just as through one transgression came condemnation for all human beings, so also through one act of righteousness came a rectification of life for all human beings; for, just as by the heedlessness of the one man the many were rendered sinners, so also by the obedience of the one the many will be rendered righteous. |

| I Corinthians 15.22 | For just as in Adam all die, so also in the Anointed [Christ] all will be given life. |

| II Corinthians 5.14 | For the love of the Anointed constrains us, having reached this judgment: that one died on behalf of all; all then have died … |

| Romans 11:32 | For God shut up everyone in obstinacy so that he might show mercy to everyone. |

| 1 Timothy 2:3–6 | … our savior God, who intends all human beings to be saved and to come to a full knowledge of truth. For there is one God, and also one mediator of God and human beings: a human being, the Anointed One Jesus, who gave himself as a liberation fee for all … |

| Titus 2:11 | For the grace of God has appeared, giving salvation to all human beings … |

| 2 Corinthians 5:19 | Thus God was in the Anointed reconciling the cosmos to himself, not accounting their trespasses to them, and placing in us the word of reconciliation. |

| Ephesians 1:9–10 | Making known to us the mystery of his will, which was his purpose in him, for a husbandry of the seasons’ fullness, to recapitulate all things in the Anointed, the things in the heavens and the things on earth … |

| Colossians 1:27–28 | By whom God wished to make known what the wealth of this mystery’s glory is among the gentiles, which is the Anointed within you, the hope of glory, whom we proclaim, warning every human being and teaching every human being in all wisdom, so that we may present every human being as perfected in the Anointed … |

| John 12:32 | And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will drag everyone to me. |

| Hebrews 2:9 | But we see Jesus, who was made just a little less than angels, having been crowned with glory and honor on account of suffering death, so that by God’s grace he might taste of death on behalf of everyone. |

| John 17.2 | Just as you gave him power over all flesh, so that you have given everything to him, that he might give them life in the Age. |

| John 4.42 | And they said to the woman: “We no longer have faith on account of your talk; for we ourselves have listened and we know that this man is truly the savior of the cosmos.” |

| John 12:47 | … for I came not that I might judge the cosmos, but that I might save the cosmos. |

| 1 John 4:14 | And we have seen and attest that the Father has sent the Son as savior of the cosmos. |

| 2 Peter 3:9 | The Lord is not delaying what is promised, as some reckon delay, but is magnanimous toward you, intending for no one to perish, but rather for all to advance to a change of heart. |

| Matthew 18:14 | So it is not a desire that occurs to your Father in the heavens that one of these little ones should perish. |

| Philippians 2:9–11 | For which reason God also exalted him on high and graced him with the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend—of beings heavenly and earthly and subterranean—and every tongue gladly confess that Jesus the Anointed is Lord, for the glory of God the Father. |

| Colossians 1:19–20 | For in him all the Fullness was pleased to take up a dwelling, and through him to reconcile all things to him, making peace by the blood of his cross [through him], whether the things on the earth or the things in the heavens. |

| 1 John 2:2 | And he is atonement for our sins, and not only for ours, but for the whole cosmos. |

| John 3:17 | For God sent the Son into the cosmos not that he might condemn the cosmos, but that the cosmos might be saved through him. |

| Luke 16:16 | Until John, there were the Law and the prophets; since then the good tidings of God’s Kingdom are being proclaimed, and everyone is being forced into it |

| 1 Timothy 4:10 | … we have hoped in a living God who is the savior of all human beings, especially those who have faith. |

New Testament Passages Dealing with Judgment and Condemnation

| Chapter and Verse | Text | Comment |

| Matthew 25 (entire chapter) | Then the kingdom of heaven will be like this. .. ‘Lord, lord, open to us.’ 12But he replied, ‘Truly I tell you, I do not know you.’ 13Keep awake therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour. 30As for this worthless slave, throw him into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.’ ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me. 46And these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.” | Matthew only. The punishment is hyperbolic and probably metaphoric |

| Matthew 8.10-12; Luke 13.28-30 | When Jesus heard him, he was amazed and said to those who followed him, ‘Truly I tell you, in no one in Israel have I found such faith. 11I tell you, many will come from east and west and will eat with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven, 12while the heirs of the kingdom will be thrown into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.’ | Matthew and Luke. The punishment which envisions the Patriarchs and the Jewish people being punished seems hyperbolic. |

| Matthew 13.41-43 | 41The Son of Man will send his angels, and they will collect out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all evildoers, 42and they will throw them into the furnace of fire, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. 43Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father. Let anyone with ears listen! | Matthew only. Punishment is absolute. |

| Matthew 13.49-50 | 49So it will be at the end of the age. The angels will come out and separate the evil from the righteous 50and throw them into the furnace of fire, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. | Matthew only. Punishment here may be metaphoric but it appears to be absolute |

| Matthew 5.22 | But I say to you that if you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgement; and if you insult* a brother or sister,* you will be liable to the council; and if you say, “You fool”, you will be liable to the hell* of fire. | Matthew only. Difficult to say whether punishment implied here is metaphoric, likewise it is unclear whether it is absolute. |

| Matthew 5.27-30 | 27 ‘You have heard that it was said, “You shall not commit adultery.” 28But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart. 29If your right eye causes you to sin, tear it out and throw it away; it is better for you to lose one of your members than for your whole body to be thrown into hell. 30And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away; it is better for you to lose one of your members than for your whole body to go into hell. | Matthew only. Matthew appropriates this teaching on temptation here in this teaching on lust. Punishment is likely metaphoric but absolute |

| Matthew 5.30; Matthew 18.8-9; Mark 9.43-45 | 42 ‘If any of you put a stumbling-block before one of these little ones who believe in me, it would be better for you if a great millstone were hung around your neck and you were thrown into the sea. 43If your hand causes you to stumble, cut it off; it is better for you to enter life maimed than to have two hands and to go to hell, to the unquenchable fire. 45And if your foot causes you to stumble, cut it off; it is better for you to enter life lame than to have two feet and to be thrown into hell., 47And if your eye causes you to stumble, tear it out; it is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than to have two eyes and to be thrown into hell, 48where their worm never dies, and the fire is never quenched. 49 ‘For everyone will be salted with fire. 50Salt is good; but if salt has lost its saltiness, how can you season it? Have salt in yourselves, and be at peace with one another.’ | Mark and Matthew; this sequence of sayings probably originating in Mark and repeated twice in Matthew refers repeatedly to Gehenna (translated “hell”). The teaching is clearly metaphoric which mitigates the threat of hell. That said, the punishment here appears to be permanent annihilation. Curiously, Mark’s statement on salt modifies any absolute threat of eternal torture or destruction. This ending is not picked up by Matthew. |

| Matthew 10.28; Luke 12.5 | Do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul; rather fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell. | Matthew and Luke (Q); the punishment implied appears to be absolute |

| Matthew 23.33 | You snakes, you brood of vipers! How can you escape being sentenced to hell?* | Matthew only. |

| Matthew 5.25-26; Luke 12.59 | Come to terms quickly with your accuser while you are on the way to court with him, or your accuser may hand you over to the judge, and the judge to the guard, and you will be thrown into prison. 26Truly I tell you, you will never get out until you have paid the last penny. | Matthew and Luke (Q) Punishment is remedial not absolute |

| Matthew 18.34 | Should you not have had mercy on your fellow-slave, as I had mercy on you?” 34And in anger his lord handed him over to be tortured until he should pay his entire debt. 35So my heavenly Father will also do to every one of you, if you do not forgive your brother or sister from your heart.’ | Matthew only. Punishment is remedial not absolute |

| Luke 12.47-48 | That slave who knew what his master wanted, but did not prepare himself or do what was wanted, will receive a severe beating. 48But one who did not know and did what deserved a beating will receive a light beating. From everyone to whom much has been given, much will be required; and from one to whom much has been entrusted, even more will be demanded. | Luke only. Punishment is remedial not absolute |

Hell Doesn’t Add Up Logically

Hart spends most of his pages arguing for the logical problems that emerge with the idea of everlasting torment. I believe that Hart is at his best making obvious the incompatibility of eternal torment and biblical faith. He raises several devastating questions like this one. Would the bad behavior of a child in a culture which never heard of Christianity truly warrant eternal punishment?

It’s the eternal part that reveals the problem. Surely, a supremely good, true, and beautiful God would not create a human being, give him or her no exposure to faith, and then after a few years of earthly existence cast that person into hopeless suffering for eternity? So, after a billion years of unabated torment we could consider the suffering just beginning.

This lack of proportionality is a glaring problem in the infernalist argument. Would a sinner condemned to such a fate remain the same person after a couple of thousand years of Hell’s fires?

One way that Christian thinkers like C. S. Lewis have skirted this ugly image of Hell is to suggest that wicked people choose their way into isolation from God and thus everlasting death. Hart regards this conception of Hell to be the infernalist’s strongest one and spends many pages arguing against it. The crux of his response is that no fully sane, enlightened person is even logically capable of choosing anything other than the ultimate good, which is God.

Apokatastasis

I said above that Hart uses the term apokatastasis only one time in his text. This is a bit misleading. The four meditations that compose the bulk of his argument Hart titles apokatastasis. Take Hell out of the theological mix. So, if you remove the possibility that God might discard some people or portions of the created world to death or torment, and suddenly you’re left with the prospect that all things will be gathered up into God’s plan.

This eventual and glorious restoration, of course, does not mean that suffering will not have a role or that biblical faith. It means that suffering in all forms is temporary and that in God’s providence all suffering serves to affect apokatastasis. One thinks of the series of exiles endured by ancient Israel and interpreted by the prophets. The prophets saw the Israel’s massive suffering. Nevertheless, they insisted that the experience contributed to the ultimate perfection of all things.

What Does All of This Mean Today?

The broad conclusion that I take from these passages is that the Universalist position much stronger in the New Testament than I expected. It is stronger still in the Old Testament.

For me, Hart met and exceeded any requirement I might have to have made his argument. Everlasting torment in Hell is out of the bounds of the traditional view of God’s goodness and the Bible is not at all focused on it. That said, I am still reluctant to state baldly that there is nothing to the widely held idea that through determination we can sin ourselves beyond even God’s willingness to save. Who does this I don’t know. But I am too intellectually timid to declare it out of bounds. There are a couple of ways that we can retain some kind of end-of-life punishment and harmonize Hart’s arguments with Church tradition.

He himself suggests unenthusiastically that some kind of after life punishment might await the worst among us to be followed by a general resurrection wherein the entire Cosmos is restored.

Second, we may take the Bible’s multiple streams of thought–infernalist and universalist–as a device to keep us from emphasizing either line. What awaits may be unlike anything we could imagine. The ambiguity of the Scriptures (which leans very heavily towards the Universalist outlook) may be a way of keeping us from settling on a rigid doctrine, which would doubtless infect the Church with unavoidable legalisms and absolutes.

Hart does not elaborate much on the implications of his work. But the reader should not miss these. To say that God created a destiny that the Church calls Hell is really to credit to God a level of moral degeneracy that many people would rise above. Imagine the mother of a notorious sinner. A parent of a mass shooter. Is there not someone who weeps over the fate of even the worst human being, the very person who we commonly think of as deserving of Hell? Is it possible that a mother weeps over her ruined and banished child, but God does not?

This logic is key to Hart’s thinking. If you believe that there is a condition and destiny of eternal torment

This thought surely alerts us to the fact that when we begin to see in God attributes that we disapprove of, that we’ve probably steered away from genuine biblical faith.

What’s more, a defective image of God tends to authorize abusive behavior in people. I wonder how many people bear scars or alienation from Christian faith because a parent or teacher shamelessly pulled out the expedient of Hell’s torments as an instrument of discipline.

Hart is reminding us that there is no such violence in the heart of God. Pointless agony that doesn’t end fits awkwardly with the otherwise glorious plan of salvation that we read about in the Scriptures. Rather the ongoing work of Creation, Redemption, and Consummation are themselves are working to dismantle any hellish circumstance that stubbornly lingers in this world. And Hart contributes with panache to this project.

Old Testament Passages that Point to the Inclusion of Animals in the Scope of Salvation

[i] Hart, David Bentley. That All Shall Be Saved (p. 66). Yale University Press. Kindle Edition.

[ii] Ibid. p. 6