Have We Come All that Far in Defeating Racism?

Three years ago, my wife and I joined an interracial book club. Each month, 10 or 12 of us get together to discuss a book selection from the large and growing list of great writings about race in America. The group includes Black and White participants. Our conversations are warm and we’ve become friends.

There’s a phrase that people like those of us in our book club say repeatedly:

“We’ve come so far.”

As we read about income disparities between different ethnicities, mass incarceration, and voter suppression, we can almost predict that someone is going to say, “Yes, it’s still bad. But we’ve come so far.”

Now that I think about it, it’s mostly the group’s White people who say that. And now as I really think about it, we don’t say that as much as we did a couple of years ago.

Of course we’ve come a long way towards racial justice…haven’t we?

At first blush, it seems obvious that racial justice in America has made solid progress. Chattel slavery ended with a stroke of Abe Lincoln’s pen in 1863. All of us in the reading group grew up in the 1960s with the Civil Rights movement and affirmative action. Oh yes, there were setbacks. A White supremacist shot MLK. On the other hand, the nation progressed to the point that we elected our first Black president.

Maybe the we’ve-come-so-far journey is a two steps forward one step backward kind of progress. But with a century and a half of two-forward-and-one-back, it still feels as if we’ve got a long way to go.

One of the first books we read was Ibram X. Kendi’s, Stamped from the Beginning. It is a history of Western Thought and it chronicles the European and American thought-habit of seeing African descent people as inferior. Right in the beginning, Kendi makes this statement:

When I first read those words back in 2018, I didn’t have enough familiarity with Black experience in America to nod in agreement as I read. But I remembered that paragraph.

Now, I’ve just finished Carol Anderson’s, White Rage. Like Kendi, Anderson is writing history. Her book surveys the long stretch from Reconstruction to Trump’s election. Curiously, White Rage has enabled me to see the truth of Kendi’s statement, namely that there are two kinds of development going on at the same time. There is progress in racial justice to be sure. What I’ve learned is that there is a counter-force that has has progressed as well.

We might sit around in our interracial book club and console ourselves, saying, “We’ve come a long way.” But the gun-toting Proud Boys, might be sitting around in smug satisfaction that their cause has leaped up from the ashes and is going strong. And even more worrisome than the neo-confederate good ol boys are the state officials behind computer scenes jiggering the voter registration rules and polling places so to stifle People of Color’s enthusiasm for voting.

We may breathe a sigh of gratitude thinking, “At last a Black President, we’ve indeed come a long way.” But then that corrosive force comes creeping out of the ground and within weeks of his inauguration vile racist tropes are spreading exponentially on FaceBook. And they’re being “liked” by some of your friends. Others are showing up at enthusiastic Tea Party rallies. And business tycoon, Donald Trump has managed to garner a shocking number of believers in his “birther” movement.

The statement that “we’ve come a long way” is a metaphor. It reminds me of a long hike. I imagine a line of pack-hunched kids—scouts–trudging up a mountain trail. They yearn to shed their packs, slip off their shoes, and just stop. Their leader encourages them: “You’re several hundred yards from the camp where you’ll have dinner and sleep. And…you’ve come a long way!”

But are race relations in America anything like a hike? Can we even see the destination?

As we’ve read I’ve learned about a group of theorists, Afro-pessimists, who have dared to think the worst about racial justice in America. Their insight is that racial injustice is an unavoidable feature of American society. In other words, we’re never going to arrive at the camp! We’re hiking in a never-ending circle. Black progress may always breed an opposing force that wants to push Blacks back.

What if we throw out the hike and “we’ve come a long way” metaphor out entirely?

I’m thinking that we should dispense with the language of progress because every time Black people have stepped ahead, every time their true dignity comes out, there is an equally creative counter force that pulls them back.

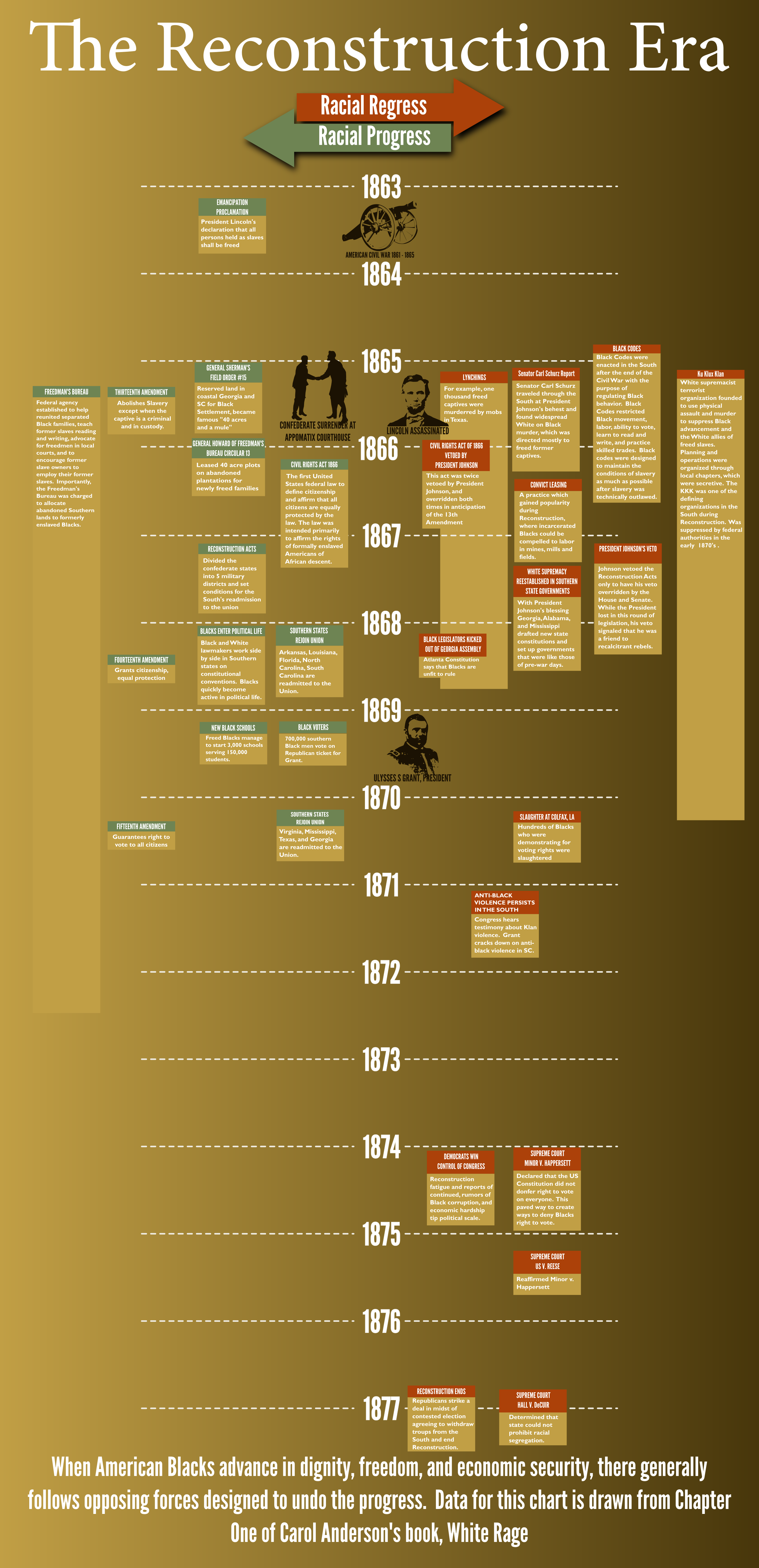

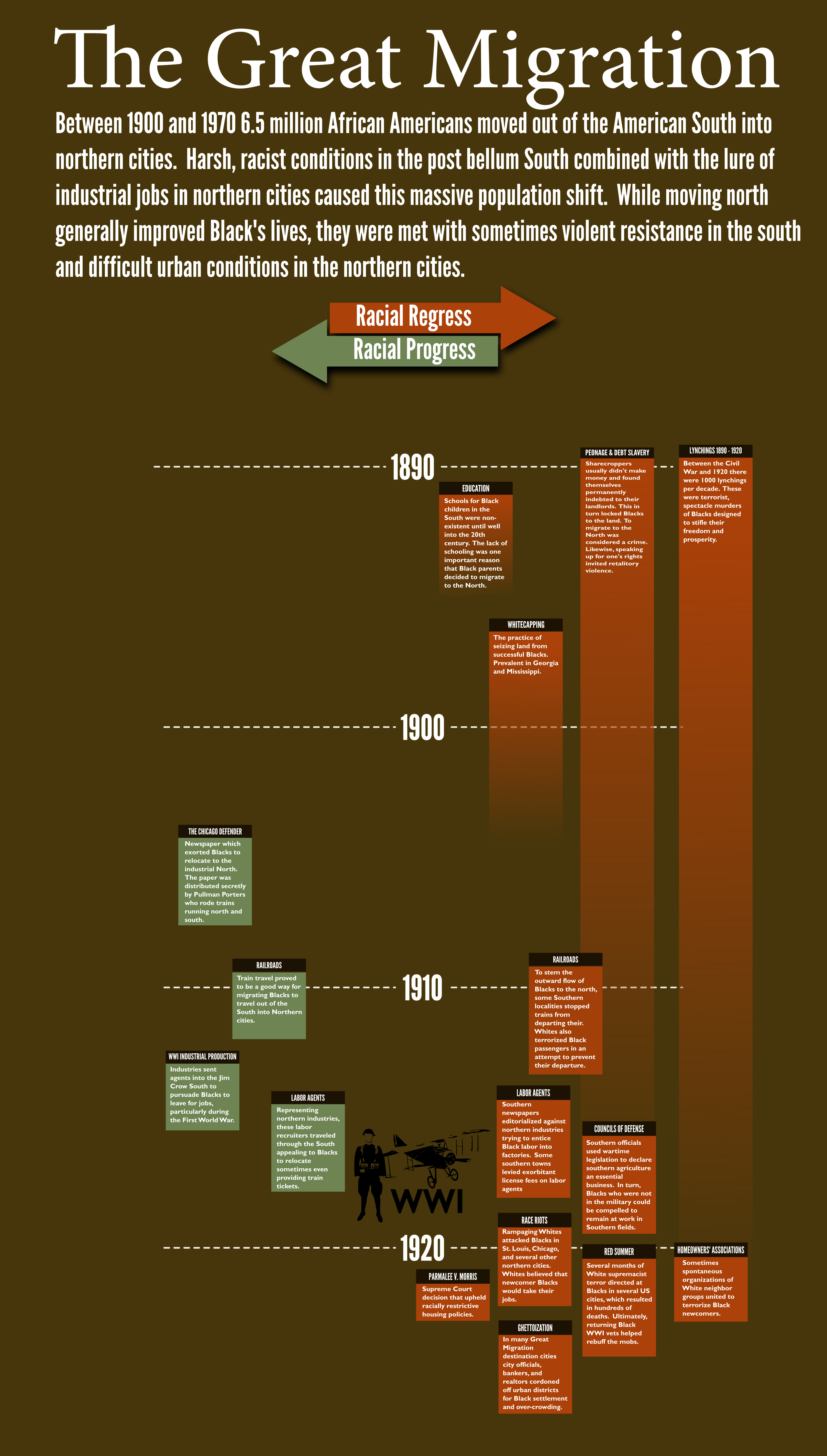

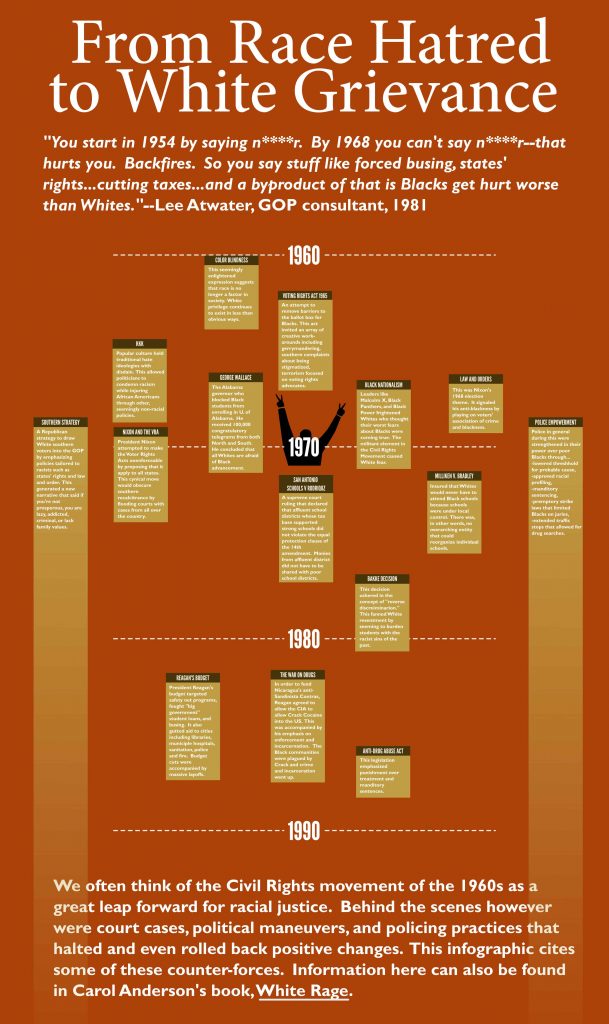

It’s that continual opposition that mocks our cheery ideas of progress and needs to be unmasked. Carol Anderson’s White Rage supplies a lot of data that exposes that destructive force. She has divided her book into 6 historic periods: Reconstruction, the Great Migration, the Brown v. Board of Education Era, the Civil Rights Era, Obama’s presidency, and the election of Donald Trump. For each period, she gives examples of White supremacist strategies that rolled back the intended progress for Black Americans.

What is the rage?

Every time I’d pick up my copy of Anderson’s book I’d see again its vivid title: White Rage. At one point I wondered if the publisher read the book, a third of which is footnotes, and found it somewhat tedious history that needed to be amped up with a lurid title.

After I finished, I re-read the Prologue, Kindling. I discovered that Anderson had stated what she had in mind with the words, white rage. Here’s how I’d put it.

The energy that lurks beneath the surface of American life and springs into action whenever Black people begin to bloom can only be described as rage. The rage looked like rage in the murderous months following the Civil War when defeated White southerners turned loose their shame and grief on the former slaves, now unchained and moving up and down the dusty southern roads trying to put their lives and families back together. Many of these newly freed people were simply murdered. That kind of violence continued with alarming vitriol for decades. It took the form of KKK night riders, lynchers, and mobs of racist “neighbors” in Northern cities.

Anderson isn’t as interested in the lurid violence as the ways the rage took respectable forms. She writes,

For me, White Rage does not end reassuringly. One might expect that a book on racial justice nowadays would freshen its reader’s image of the Promised Land and then give a pep talk designed to get the hike moving again.

Anderson gives instead a sustained look at a society possessed by a permanent impulse to oppose African-descent people. That impulse has been around since at least the 19th century. In the main, it has shed its hoods, swastikas, and hate language. Respectable now, it can inhabit both political parties, most blatantly the GOP. That’s not progress. It’s evidence of rage adapting to the world around. Racism has a college education now. It has put on a necktie. It doesn’t use the n word anymore. And it doesn’t appear to be tumbling into the dust bin of history.

For me, White Rage’s value was the way it organized a confusing pile of historical data, much of it a tad boring like stories of legislation, court cases, and policy decisions. It illustrates Kindi’s point that anti-racist progress tends to be matched with racist progress. I found Anderson’s chapters to be troves of information about how racism has countered efforts to advance the cause of African Americans. But even more valuable the chapter arrangement makes it clear that all of the sneaky devices respectable White people have used to frustrate Black flourishing are reactions to Black progress, usually going on at the same time.

Reconstruction

It was during Reconstruction, the period covered by the first long chapter in Anderson’s book, that the push-forward-get-pushed-back dynamic began. The Emancipation Proclamation and 13th Amendment, signal achievements of Reconstruction, would appear to end slavery once and for all. Unfortunately, many White Americans struggled after the end of the Civil War to reinstate a kind of new slavery for Black Americans. This was first done by passing Black Codes which strictly regulated the behavior and movement of the newly freed slaves. The Black Codes morphed into the long-lasting Jim Crow practices, which enforced a two caste system in American society.

The infographic below illustrates and dates several additional examples of the back and forth between racist and anti-racist energies during Reconstruction.

Much the same could be said of the other historic eras that Anderson covers. I’ve created two additional infographics, one on the Great Migration Era and the second on the Civil Rights Era, which give a vivid sense of the tactics politicians and White citizens used to stifle Black development:

Insurrection, January 6, 2021

I was mid-way through White Rage when the January 6, 2021 Capitol Riot took place. In some ways, the Capitol insurrection was a wholly unprecedented event, with its motley crowd of invaders many of whom were in the thrall of a bizarre conspiracy theory. The targets of the rioters were white lawmakers and even the Vice President.

Anderson’s book gave me bold insight into what was going on. In the weeks before the riot there had been significant advancement of the rights and strength of the African-American community. Police abuse had been dragged into the bright light of public attention following the George Floyd murder by police in Minneapolis. President Trump lost his bid for a second term to a Democratic ticket which included a non-White woman, Kamala Harris. Perhaps most importantly, Georgia appeared to flip from being a solid red state to solid blue. This development was the fruit of a massive voter registration effort led by Staci Abrams. Blacks had advanced.

If history is to guide us, we would expect an outbreak of White push-back. And there it was in the form of a motley mob egged on by not only Trump but by dozens of legislators, right-wing journalists, and a considerable minority of the American citizenry. As the riot developed and then in the days that followed I had the sense that pundits were struggling to orient themselves to what had happened. I too could not have predicted the events of that day, nor the vastness of the approving public watching from home.

One thing I did know. The Capitol Invasion was reminiscent of a long tradition of violence directed at Blacks and their supporters. This was the old white rage. The Capitol riot was unique but also strangely familiar. We’ve seen this before.