From Chaos to Satan: The Story of Evil in the Bible, Part 1

The inspiration for this two-part post comes from Bernhard Anderson’s brilliant study Creation Versus Chaos, written in 1965. The decade of the 60s was a time when scholars were beginning to realize that Christianity needed to re-consider the Old Testament’s creation texts and the role of creation in Christian faith.

Creation is much more than a passive stage on which the drama of salvation is played out. The created world is an actor in that drama. When we understand more about creation’s character and destiny, we find that it sheds a much-needed light on some fundamental doctrines in biblical religion, including how God interacts with the world, people’s role as God’s partners in creating, and where the world is ultimately heading.

Evil is another important religious idea that, when viewed from the standpoint of creation, can come into much clearer focus. This is the aim of these essays.

The first three chapters of Genesis don’t record any creation of evil. There’s no devil. Neither is there any adversary to counter what God is doing.

Despite these apparent omissions, lots of bad things happen and suffering is rife. By the time we get to Jesus’ public ministry as recorded in the four gospels, we find him interacting daily with Satan, the Devil, and demons.

These two essays will trace the process that led to the development of personified evil which runs through the Bible.

Chaos as God’s Adversary

The Bible’s foundational tension is between God and chaos.

That’s a stark statement. Most church attenders, most ministers, would find such a statement puzzling. I would have found it puzzling myself 5 years ago.

We can sympathize with Christians for missing chaos as God’s prime opponent in the Bible. Consider what happens when someone goes to church? At the beginning of a worship service the congregation recites a prayer of confession. “We’ve done something wrong either as individuals or as a group or nation.”

The remainder of the worship service gives reassurance that whatever evil we’ve done, there is a savior and grace that forgives and helps us do better next week.

The Bible reinforces this good vs. evil tug of war. If we’re Bible readers, we find in the Gospels a feud between Jesus and Satan’s order of evil. Additionally, the Old Testament contains the Ten Commandments and other behavior standards. The sweep of the Bible story opposes sin and evil in favor of righteousness and goodness.

Without denying the New Testament’s obvious good vs. evil tension, I’m pointing to a deeper drama, namely the vacillating struggle between God’s creative work and chaos. This struggle begins in the Bible’s first verses. Here in the opening of Genesis, the Creator makes cosmos out of chaos. Then God continues this creating work. As the biblical saga develops with Abraham’s call and the story of his offspring, creation moves beneath the narrative’s surface, poking up occasionally in places like the prophets and wisdom writings.

In the New Testament, the blazing Christ event overshadows the ancient tug of war between creation and chaos. Then at the end of the New Testament, Creation emerges grandly in the book of Revelation when God takes up residence with his people in a glorious New Creation.

Creation by Stages

God fashions the world in Genesis’ first 3 chapters, by stages. Instead of making everything appear in an instantaneous “poof,” the Bible’s creator returns daily to the work like a construction worker showing up for a succession of eight-hour shifts.

Unexpectedly, God enlists humans (Genesis 1.28), the earth (Genesis 1.11), water (Genesis 1.20) and an unexplained spiritual council (Genesis 1.26), in the effort.

As the first week of creation progresses, God assesses the project and declares what the community of creation had accomplished was “good,” (Genesis 1.12, 18, 25, 31). The creation project hasn’t reached perfection, but it was headed in the right direction.

In the Garden

There’s a second creation story in Genesis 2 and 3 that brings to light more of the interrelationship between God, people, and the created world. This story narrates how God makes a human, animals, and a second human, the woman, out of pre-existing materials, namely the ground (Genesis 2.19) and the man’s body (Genesis 2.21).

Genesis 2 gives the reader a picture of Eden as a workshop where God and humans work to bring forth key parts in what is becoming a splendid world. The humans are an important part of this effort, for people will have replicate themselves, till the earth, name and look after animals, oversee the land, and enjoy themselves.

Bible scholars have used the words “partners” and “co-creators” to describe humanity’s vocation in the garden. This level of responsibility also implies how destructive humanity can be when it strays from God’s intentions.

The Entry of Evil

While evil as an entity is not resident in Genesis’ texts about creation, the second and third chapters explore in some depth how big problems arise, effect God, cause suffering, project destruction into areas of the world that we would consider unrelated, and threaten the continuation of the entire creation project.

The source of problems stems from the structure of the human, and possibly from the Creator. People may be powerful world-makers at God’s side, as was Noah. Or they may be shockingly destructive as was the Pharoah in Exodus.

Because God entrusted humans to function as partners in the creation project, their rebellion against God has power to damage the world’s structure. Human disobedience in the garden is like a dishonest construction worker’s betrayal. He works to build the house while the boss is looking, but then returns after dark to steal the windows and lumber.

The story of the Garden develops and illuminates how misguided human independence can bring creational disaster. Take, for example, the consequences (Genesis 3.8-19) that follow the man and woman’s mess-up in the Garden of Eden. Their lapse in trusting God and eating the fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, results in interruptions in their tasks as God’s creative partners. (Genesis 3.13-19)

Three examples illustrate: First, difficulties that come to women in childbearing (Genesis 3.16). These block them from fulfilling their vocation (Genesis 1.28) to fill the earth with offspring. Second, the garden loses its fruitfulness (Genesis 2.15, 16). Hardship in farming and getting food replace the world’s former abundance. Third, the snake that God entrusted, with all animals, to the loving care of humanity, (Genesis 2.18-20) finds itself in conflict with the woman.

The collateral damage that results from the human’s mistrust and disobedience slows the entire creation project, causing a partial lapse back into chaos. The Bible is not explicit in spelling out the cause and effect that I’m trying to sketch here. What the Creation and Garden of Eden stories do is to suggest the world’s spiritual structure and people’s potential for good and ill that will continue through the Bible and into the present.

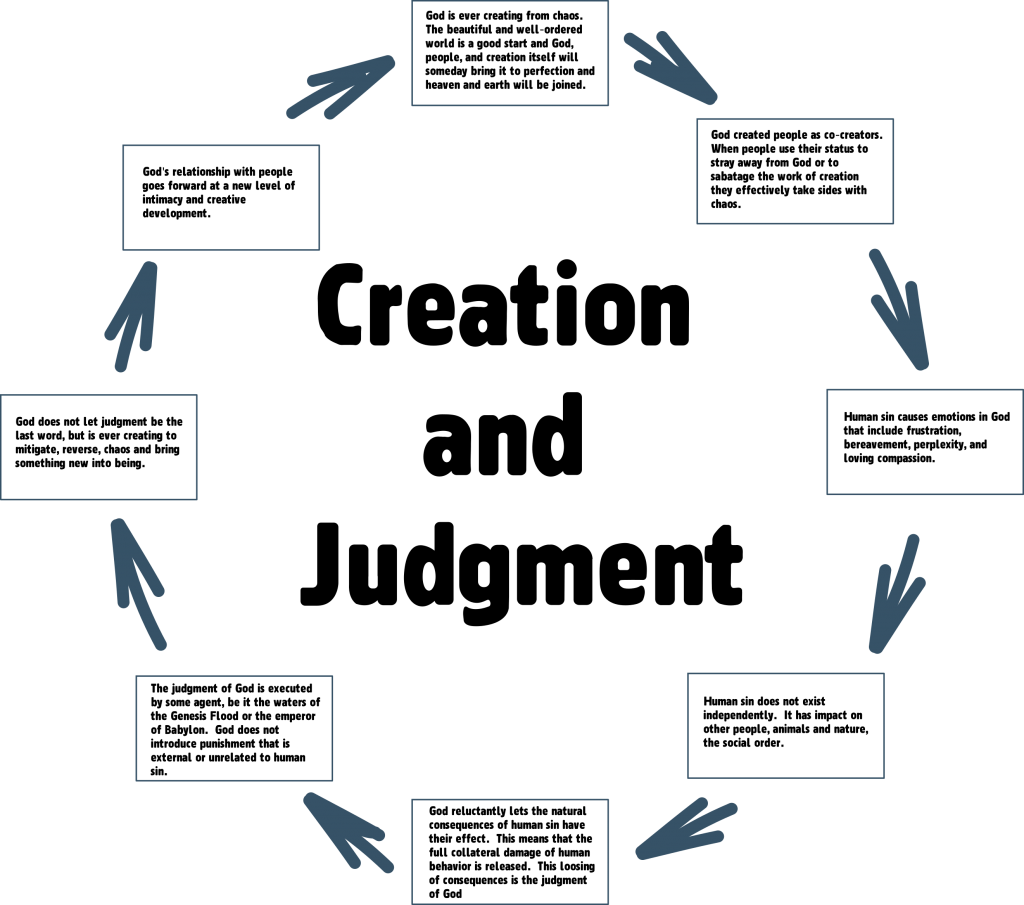

Genesis’ first three chapters begin to bring into focus an eightfold pattern that will repeat throughout the Old Testament:

It’s important that the reader not take this chart as a checklist of factors which will appear in every Old Testament story where there is sin and judgment. The Hebrew Bible is not a geometry textbook. It does not see faith as resting on doctrinal syllogisms. The point of the chart is to suggest a coherence shared by several Old Testament stories and their connection with chaos.

Three Examples of Sin Rolling Back the Creative Order

The Genesis Flood and Noah’s Ark

Of course, the story of the flood and the ark are well known. On the heels of the Garden of Eden story, Genesis leads the reader into a dark situation where humanity’s sin has reached huge proportions. God is clearly disappointed, angry, and bereaved. Popular piety is less aware of how the Flood story repeats the Garden of Eden story, and how the fivefold pattern helps interpret it in the language of creation.

The Bible says that God reacts to humanity’s sin by vowing to destroy people and animals (Genesis 6.7, 13). When, however, we read through the Flood story, God’s behavior is much less furious and domineering than tradition leads us to believe. The Bible tells us of God’s bereavement and God’s productive partnership with Noah to save a portion of the living world.

Additionally, the Flood itself is the undoing of the second day of creation (Genesis 1.6-7) Unruly waters gush in from above and below and leave the world uninhabitable.

The principle of environmental disruption following moral or societal disruption, first laid out on small scale in Eden, has now reached monumental proportions. No catastrophe in the Bible or throughout history, except for climate change, rivals the Genesis Flood in scope.

The eightfold sequence sheds light on this remarkable tale. We have the proximity of human wickedness and environmental disaster. The disaster is indifferent to the innocent victims and causes incalculable suffering. God does not act in domineering power to reverse the situation but strikes up a partnership with Noah.

This partnership builds a spectacular wooden boat, the largest sea-worthy vessel ever said to exist, and fills it with representatives of the animal and human world to provide the seeds for a restored creation. God pushes the waters back and up again, though Genesis’ text is silent about God’s role in this operation.

The story culminates with God’s promise never to send or allow such a disaster to happen again. This latter gesture is a development in God’s relationship with the world that needs its own essay to elaborate. At least, the rainbow covenant is a grace that follows the eightfold pattern we’re describing.

The Plagues of Egypt

The pattern of sin, de-creation, suffering, and divine compassion comes up again in Exodus, notably in Exodus 7-11, the plagues chapters. The oppression of enslaving the Hebrew people plus the Pharoah’s self-elevation as a god are social injustices which register as ecological disruptions. Modern readers recognize the sequence of foul water, fleas, flies, and frogs as an unbalanced ecological system. Or, to interpret the plagues in the thought pattern of creation, disorder in the social sphere reverberates as disorder in the natural world.

Then, as we would expect using the pattern in the eightfold cycle, God’s compensating grace follows. In this case, the people escape the Pharaoh’s empire, now in shambles due to the plagues. God pushes waters back to rescue the people from Egypt’s infantry and makes streams flow to quench the people’s thirst. Food is adequate for the large crowd of people in what should be an uninhabitable desert. Not only do the people escape, but they receive a law code on Mt. Sinai, which sets them up to be a free and enlightened nation.

The Prophets

The Old Testament prophets represent the zenith of Israel’s understanding of God and their place in God’s world. The famous writing prophets, like Jeremiah and Isaiah, recorded their oracles in the period leading up to the deportations at the hands of the Assyrian and Babylonian armies. The powerful armies of both aggressors from Mesopotamia to the north overrun Israel and Judah and march their leadership class into forced settlement in Assyria and Babylon respectively.

The prophets’ job is to warn of the coming armies and to disclose the spiritual reason for the approaching misfortune. Israel and Judah are, according to the prophets, wicked. They have strayed away from their divinely given reason for existing. And they have walked away from their commitment to the covenant they made with God at Mt. Sinai.

Significantly, some of the points on our circle appear in the thinking of the prophets. Israel and Judah’s leaders lead the people into geopolitical maneuvers that completely forget about God. Foreign religious practices creep into Judah’s life. The prophets report God’s sadness and frustration over the people’s waywardness. At length, God permits foreign armies to overrun the land and carry off the people.

This conquest is how God expresses God’s judgment. God’s hand never hurts or destroys. In some unexplained way marauding armies in biblical thought somehow equate to a resurgence of chaos. Additionally, the destruction brings collateral damage even to animals and what we would call the “natural” world. This happens because of the interrelationship between God, Israel and her people, other nations, animals, and the non-living created order.

As we might predict using our eight-stage cycle, destruction or the intensification of chaos is not the last word. God’s creative work presses forward and new creation follows Exile. In the case of Israel’s experience of exile, we see an array of creational green shoots cropping up from the ashes of destruction and scattering. The Jews gain a new outlook towards faith in God. Rabbis develop the scriptures and Talmud. A new opportunity to return to the homeland happens. Ultimately, a Messiah comes in the birth of Jesus Christ.

This cycle appears to lie beneath the surface of the writing prophet’s thought and is especially prominent in Jeremiah and Second Isaiah, the portion of Isaiah written after the Babylonian Exile. Jeremiah 4.22-28 gives a vivid example of how Judah’s sinfulness and the prospect of its destruction spills over into the natural world.

“For my people are foolish, they do not know me; they are stupid children, they have no understanding. They are skilled in doing evil, but do not know how to do good.” 23I looked on the earth, and lo, it was waste and void; and to the heavens, and they had no light. 24I looked on the mountains, and lo, they were quaking, and all the hills moved to and fro. 25I looked, and lo, there was no one at all, and all the birds of the air had fled. 26I looked, and lo, the fruitful land was a desert, and all its cities were laid in ruins before the Lord, before his fierce anger. 27For thus says the Lord: The whole land shall be a desolation; yet I will not make a full end. 28Because of this the earth shall mourn, and the heavens above grow black; for I have spoken, I have purposed; I have not relented nor will I turn back.

Summary

This essay is a study of evil in the Old and New Testaments from the perspective of a biblical theology of creation. We’ve investigated evil’s nature and origin. Here is what we have put forth:

- The first verses of the Bible picture the Creator God bringing order to chaos. God does not finish his effort in world-making in a snap but stretches it over the first 6 days and beyond. In the process, the Creator recruits the earth itself and seas to bring forth animals. Later God involves humans in the naming of animals and shared responsibility for overseeing the well-being of all things.

- Very quickly, humans betray at least in part their vocation to be co-creators with God. This betrayal, this “sin,” proves to have extraordinary power to disrupt the progress of creation. Creation includes more than rocks, trees, and living creatures. It also includes rightly ordered relationships, such as marriages or financial fairness in society. So disturbances in one area might register in another, seemingly unrelated area. The pharaoh, for example, puts onerous work burdens on the captive Hebrews and the Nile turns red.

- At some point, God reaches a level of frustration and disappointment that we might describe with the colloquial, “Enough is enough.” When this point is reached, God permits the consequences of sin to take their natural course. God does not introduce punishment into the world, which brings destruction to creation, but God will permit some agent or nature itself to execute judgment. The waters of Genesis’ flood or the Babylonian emperor, Nebuchadnezzar, are two examples of such agents.

- Happily, judgment and disruption is not the final word. And judgment gives way to some new form of creative energy.

- As to the idea of evil: the creation story envisions no entity like a Satan that exists independently from God. Through the Old Testament and preeminently in the Prophets, evil has its origin from within the created world. There is no outside cause, like a devil, who’s existence is independent of God and who acts as a prime adversary.

- Accordingly, our first statement, that the Bible’s primary tension is that between God and Chaos, still appears to be true.