Debby Irving’s Heroic Journey

That first reading left me with three impressions.

- Debby Irving was diabolically skilled in describing the values of the household she grew up in—values that were similar to those in my parents’ home

- The author struggled for years trying to reach an elusive goal of racial reconciliation or justice.

- The book contained a number of astute insights into how an affluent White suburban lifestyle by its very nature works to freeze in place the oppression of people of color in America.

Debby Irving

The book is also filled with eye-opening stories. One example of the way hidden decisions benefit Whites at the expense of their Black neighbors is when city officials quietly restrict Black kid’s access to shopping malls. A group of Buffalo, New York businessmen decided to jigger the city bus schedule in order to keep inner city kids out of a new mall. This led to the death of a Black teenager, Cynthia Wiggins, as she attempted to cross a busy street in order to reach her job in mall’s food court.[1]

Waking Up White gives dozens of ways that the ethos of the White middle class, people who may feel no animus towards their Black neighbors, still sets up a society that subtly locks Blacks out of prestige and prosperity.

Debby Irving grew up the youngest in a prosperous, intact New England family. She was raised on the Yankee ideals one would expect in the land of abolitionists and Harvard University. Some readers find Debby’s iconic childhood off-putting. They may rightly observe that Debby had advantages that even her readers did not enjoy. But that fact makes Debby’s point all the more powerful. Debby grew up never hearing the N-word. Her parents would never march to resist forced busing for public school de-segregation. Her grandfather wasn’t a Georgia farmer who employed share croppers or rode with the Klan. She didn’t come from steel workers who used without apology racist lingo to typecast people of different backgrounds.

Debby’s childhood floated serenely above all racial tension. It bristled with work, crafts, skiing, holidays, and family vacations. Underlying this wholesomeness was a philosophy of aspiration and work. Her parents instructed Debby with a stern ethic of honesty. In one uncomfortable story, Debby describes her father driving his daughter back to a dime store so she could return a small item that she had stolen. The trip included an apology and a walk around the store to help Debby understand why stealing hurt the employees.

Debbie describes her childhood ideals to set the stage for her life-long quest to separate herself from them. Waking Up White’s essential brilliance is that it exposes even the best of these values as the “elephant in the room,” which prevents well-meaning Whites from connecting with Black neighbors to overcome America’s persistent race trouble.

…what grabbed me was Debby’s yearning to step out her family culture…

I read the first half of Waking Up White knowing that it was a book primarily about race. But what grabbed me was Debby’s yearning to step out her family culture. Despite the fullness and self-satisfaction of Debby’s home, she could never adequately come to terms with the fact that other people, people of color, lived in smaller houses and struggled to keep their households together. No explanation for the disparity satisfied her, even as a child.

Debby Irving was never able to shrug off the fact that many, many people, Blacks and other ethnic groups, lived hard lives, while her own clan was comfortable, apparently because they had lived upright, hardworking lives.

Debby spent the first half century of her life trying to improve the situation. As I read I kept thinking that the best word to describe Debby’s quest was differentiation. She didn’t cut off her mother and father or become estranged from her family. But step by step she was realizing that the very habits and values that seemed so wholesome were contributing to the racial divide. It was this quest that grabbed me. I read and wondered what her parents thought of their daughter. I wondered what Debby was really thinking about her hometown. What would drive a person to continue to love and visit her family, but to take off the pedestal such values as hard work or family loyalty?

A Familiar Path

The book club spent a little over an hour discussing Waking Up White. As the meeting came to an end, the members elected to move on to its next book. I left that meeting feeling that there was more to Irving’s book than I had absorbed on my first read-through. As I began thumbing through the book again, I noticed that Debby repeatedly uses the word journey to describe her life’s course, or at least that part of her life that was looking for understanding between races. She uses journey 30 times through the book, in every instance to describe her efforts to evolve in her understanding of race.

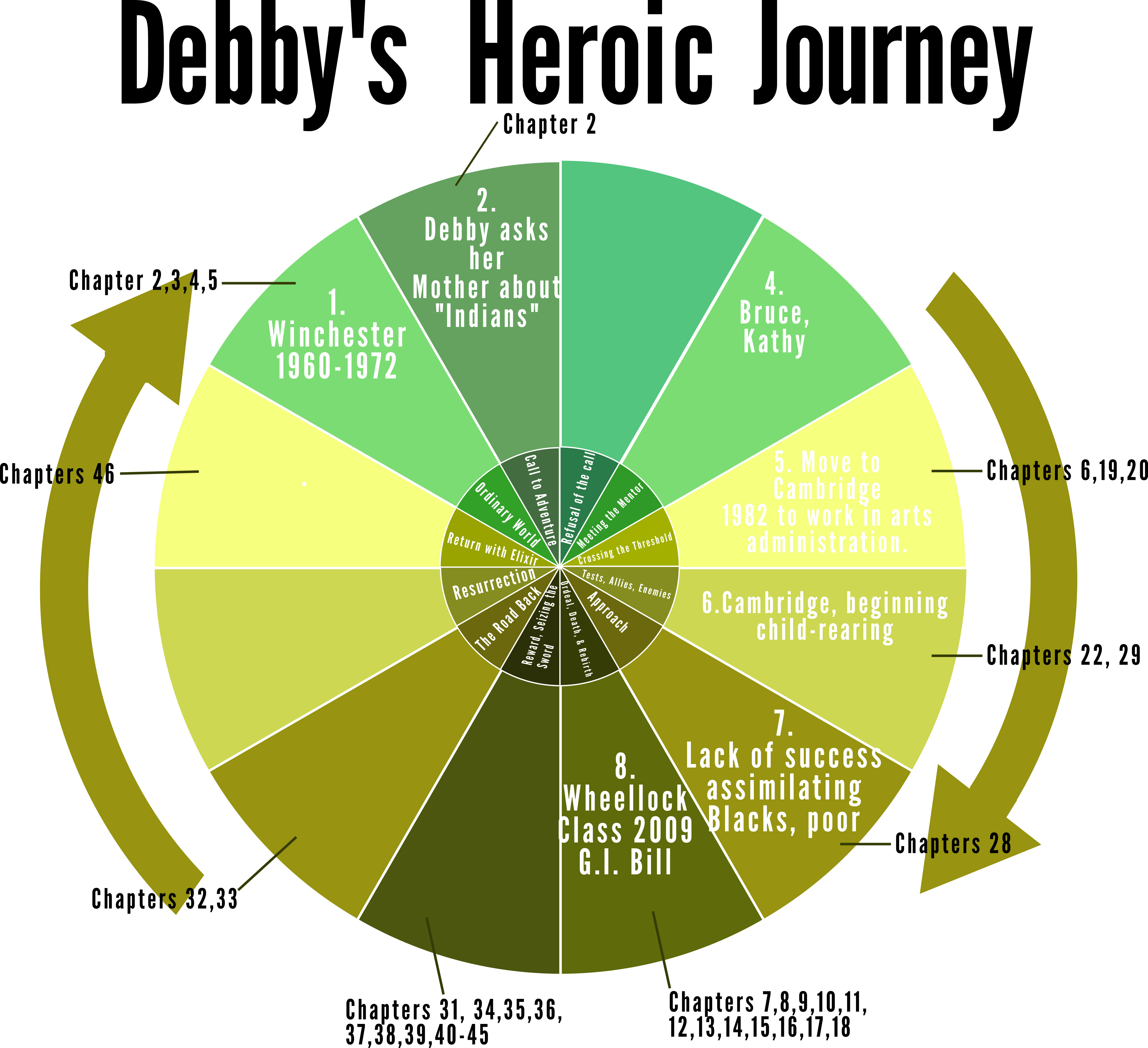

Debby’s persistence in calling her quest a journey triggered a wild idea. I thought, “This story looks a lot like Joseph Campbell’s monomyth or framework for the hero’s adventure.” The late Joseph Campbell was a professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College. He realized, after surveying the vast body of story-telling from ancient cultures around the world, that the myths of various traditional cultures have similar plots. The most famous of these plots is the quest of the hero. The hero leaves the comfortable home or village, undergoes a series of challenges, descends into danger, and then returns to the village bearing some kind of prize which benefits the whole society.

I’m convinced that Debby Irving’s life story bristles with several of the characteristic features of the hero’s journey. Like the iconic hero, Debby leaves a comfortable home base, crosses into challenging territory, descends into a dangerous abyss, and returns with something useful.

I wrestled with the thought that Debby’s quest lacked the swashbuckling drama of Bilbo Baggins journey into Mordor or Odysseus’ travels on the high seas, both classic hero adventures. Additionally, I didn’t want my fascination with solving some fanciful puzzle to cause me to miss Waking Up White’s clear point. This book is about racism after all. But her insights about race were tied to her “ah ha moments,” which she gained through the conversations and mistakes and break throughs of her life. Other questions popped up. “Does Debby see life’s path as a hero’s journey? Does she want her reader to detect it?”

I kept thinking, “There is something tantalizing about this story. But are there enough features of the Hero’s Journey in Debby’s life path to qualify it as heroic?”

I printed out a simple chart of Joseph Campbell’s plot points in the hero’s quest. I re-read Debby’s book, noting on the chart where her personal turning points resembled what heroes go through. The more I scribbled notes on the chart the more obvious it was that Debby Irving has been on a quest. She doesn’t kill a dragon or bring home the Holy Grail. But she exposes the demon of racist ideas hiding in her family’s value system. And she records the entire adventure in her book so her readers can make the same discovery.

I can think of no bigger misstep in American history than the invention and perpetuation of the idea of white superiority.–Debbie Irving

One of the problems in comparing Debby’s life course with the waypoints of the hero’s adventure is that Waking Up White jumps around chronologically. Debby begins with her childhood. No surprise there. She lays out the idealism of the household where she grew up in. She ends her book at home at her dying father’s bedside. So there is a sense of a completed loop.

Through the middle of Waking Up White the reader may miss the distinction between the author’s mature post-Wheelock insights and her frustrations as a young teacher trying to be a positive force for racial justice. For example, chapters 7-18 report Debby’s mature insights that she gains mostly through the Wheelock class. Chapters 23-25; and 27 discuss Debbie’s frustration over why her efforts at outreach to Blacks during her parenting and teaching years were awkward and not entirely successful. This latter chunk of experiences occurred years before her Wheelock epiphany.

Since I read the book hurriedly the first time through, I got mixed up and missed the dramatic epiphany Debby got late in life, namely that her own Whiteness was the “elephant in the room,” which was a barrier to her being a force in dismantling the racist system in America. To oversimplify, all of her efforts in the years before Wheelock were shortsighted and hollow; all of her engagement after 2009 was transforming and healing.

If the reader reads not simply for the insight gems about race, but also for the author’s personal drama, Waking Up White reveals an adventure that has the shape of the great quests about which the ancients wrote.

The Ordinary World

According to Joseph Campbell’s framework the hero’s story begins in ordinary life. The ordinary world is a stable and all-too-comfortable place where the would-be hero is born. There is usually some kind of far-off threat to the ordinary world that can only be defeated by a courageous individual who is willing to take a challenging journey in order to do battle with some evil force.

Debby’s ordinary world was the upper-middle class Boston suburb of Winchester, a comfortable community of stately houses and manicured lawns. Debby grew up with an unspoken assumption that her clan and community represented an ideal of enlightened living, consisting of prosperity, family values, and wholesome fun. The problem with the Kitteridge household and Winchester during the 1960’s was that it left Debby with no plausible reason why Native Americans and Blacks had never come to enjoy the same kind of comfort and serenity that Debby enjoyed.

Even as a child, Debby is beginning to notice the cracks in her parent’s world. In one notable instance, Debby’s mother is unable to explain why Native Americans are neither as visible nor as prosperous as the children of the European settlers. Debby’s mother explained the demise of Native Americans as a result of alcohol addiction, a personal weakness. The inference that a child might make upon hearing such a story is that her own family is much more prosperous than most Native Americans, therefore one’s own family must not have a weakness for alcohol.

The author recalls this brief conversation with her mother as an example of what Debby would years later unmask as the myth system about non-White peoples that worked seamlessly with other values—honesty, hard work, generosity, tact, and the like—that were her family’s guiding principles.

Debby’s ordinary world was her childhood home in Winchester with its serenity and self-satisfaction that was partly based on misinformation about non-White people.

The Special World

Joseph Campbell’s framework always entails a hazardous journey into a strange world. Debby doesn’t sail away or don armor and ride into battle. But she does leave the safety of family and suburb. She goes to Cambridge, with its mix of peoples and ideas. At 22 with her college degree from Ohio’s Kenyon College in hand, Debby moves to Cambridge, a Boston neighborhood. This move allows Debby to hold three jobs as an administrator for arts and theater organizations.

Working museums and concert halls, Debbie is especially energized by organizing special projects, which bring inner city kids to experience plays or the museums.

It would appear that these efforts to bus underprivileged kids to concerts and museum exhibits would be precisely the kind of generosity needed in order for children to be lifted out of their culturally depleted homes. She reasons, “If only these kids could experience a good play or exhibition,” she reasoned, “surely they would grow up seeking out such refinement—just like White folks.” Curiously, none of these projects are ever as successful as the planners thought they would be. Debby’s efforts are laudable, but, as she later admits, her mindset is still in Winchester with her prosperous White values.

When I got honest with myself, I had to own up to the fact that I’d bought into the myth of white superiority, silently and privately, explaining to myself the pattern of white dominance I observed as a natural outgrowth of biologically wired superior–Debby Irving

As Debby nears her “retirement” after 10 years in arts administration she helps lead a feedback session to evaluate her First Night Neighborhood Network New Year’s Eve Arts Festival. A small group of artists, administrators, and participants gather to share impressions. In the discussion, one Black teenage boy blurts out, “Man it was freaky. I’ve never seen so many white people in my life! I was scared!”[2]

This is simply a kid’s comment. But for Debbie it crystalizes her uneasy feeling that her passion for busing poor kids to art museums might be doing more harm than good.

Debby, now married and expecting her first child, makes an all-important decision. Though it would be sensible and feasible to move into a suburban existence like Winchester, she would miss the mix of peoples from all over the world, the intellectual energy that radiated from Harvard University and Boston, and the buzz of city life. Additionally, Debby will inhabit her new world more deeply, working as a teacher and rearing her children in a Cambridge neighborhood. With this decision, Debbie has stepped out of her ordinary world into the world of her quest.

Struggles

In the archetypal hero’s journey, the protagonist undergoes a series of tests which culminate when the hero descends into an abyss or a hell-like pit. In the underworld there is sometimes a marriage of the hero and the Queen of the Underworld. Sometimes the hero steals a key or elixir that will eventually prove life-giving once it is brought back to the hero’s ordinary world. The overall impact of the ordeals in the Special World are to bring a death and resurrection to the hero. In other words, this venture is life-changing for the hero, a transformation that will prove beneficial to the folks at home in the ordinary world.

Nothing so exotic, nor complex, happens with Debby. She lives an ordinary life as mom and teacher. But there is a struggle in her efforts to help non-white people. In her “struggle phase” Debby is a regular attender diversity workshops. Then she organizes her own workshops aimed at combating the race divide.

Understanding whiteness, regardless of class, is key to understanding racism.–Debby Irving

During this long phase, Debby feels awkward or unfinished. At one point she writes of the divide between her life in Cambridge and her life growing up: “So I lived with a foot in each world, needing both, never mixing the two, and often playing down the world I’d come from, the whole while feeling like a hypocrite.”[3] After working doggedly to help one struggling student, Jared, Debby concludes sadly, “I felt utterly unable to help him cope with what I was learning were two cultures on a collision course. With my growing consciousness of the way Jared and I had each developed our sense of worth and place in the world, I felt discouraged by racism’s intractability.”[4]

The Mentor

Surprisingly, the hero’s journey is not an individualistic quest where one super-talented warrior saves his civilization by dint of his or her native abilities. The hero is often quite ordinary. What enables him or her to succeed at the all-important adventure is the guidance of a mentor.

In Campbell’s scheme the mentor typically comes into the story before the protagonist crosses the threshold into the Special World. The only figure who comes into Debby’s life at that point was her husband Bruce, a companion who was very helpful and supportive of Debby’s quest.

Just before Debby enrolls in “Racial and Cultural Identity” Class at Boston’s Wheelock College where she was doing Master’s degree work in Special Education, she has a awakening conversation with a friend named Kathy. Kathy gently pointed out to Debby that White people have race in the same way that brown and black skinned people belong to racial groups. As simple as this may sound, it helped Debby at 48 realize that she thought of her own race to be the state that all peoples aspired to imitate.

It turns out that Kathy had entered Debby’s life way back when the two of them were young mothers in Cambridge. The had long been girlfriends and enjoyed having coffee together. Kathy was Black, from Trinidad, and 15 years younger than Debby. The conversation gave Debby the long-awaited key that unlocked the next phase of her journey, based on the insight that her own middle class White value system was the barrier that was holding Debby back.

Debby writes: By 2009, the year the Wheelock course finally broke me open, I had spent twenty-four years trying to “help” and “fix” others so that they could “fit in” without once considering my role in perpetuating the dominant culture that was shutting them out…I knew there was an elephant in the room. I just didn’t know it was me.”[5]

The Elixir

An Elixir is some kind of medicine. The heroes in the ancient stories would always carry back to their ordinary worlds an Elixir, which was the ultimate prize gained through their adventures. In Debby’s story, the elixir is her hard-won discovery that the structure of her life, her ideals, assumptions, and the price of her privilege is the core problem that blocks racial progress.

I toyed with analogies that might illuminate what Debby discovered. At the risk of over-simplification, this well-known story from the history of medicine serves as a fair parallel. In the mid-19th century in Vienna there were hospitals devoted to childbirth. The idea was that childbirth under a doctor’s assistance was safer than childbirth at home or with a midwife. Except in Vienna in 1846 the death rate from “childbed fever” of birthing mothers was 5 times greater than that of non-hospital birthing mothers. Ignaz Semmelweis, the famous physician who eventually discovered why the infection rate was so high, tried all kinds of adjustments in the hospital routine, including asking the priest to stop ringing a bell when he visited patients. At length, Semmelweis realized that the infection was being carried on physicians’ hands. The use of chlorinated water for hand sanitizing revolutionized the safety of the maternity ward.

Privilege is a strange thing in that you notice it least when you have it most.–Debby Irving

A revelation for Debby, one comparable to the hand-washing epiphany, came when she learned the whole truth about the G.I. Bill benefits. Debby’s parents were propelled decisively into the middle class because her father was able to reap its benefits. Says Debby, “…The bill allowed my father to go to law school without paying a dime, assured that his white parents could retire comfortably with the aid of the Social Security program, an earlier government program tilted heavily in favor of white people.”[6]

Debby’s eyes were opening to something that had eluded her for decades, namely that American society provided advantages to her family, her forebears, her neighbors, and her entire race that it withheld from people with brown and black faces.

Debby’s eyes were opening to something that had eluded her for decades, namely that American society provided advantages to her family, her forebears, her neighbors, and her entire race that it withheld from people with brown and black faces.

The fact that Debby was in a position to organize bus trips to the art museum, convene diversity training, and become an advocate for racial reconciliation was based not on her achievement becoming prosperous, but on an unfair distribution of entitlements.

Once Debby heard of the GI Bill’s blatant injustice, she moved on to discover several additional ways that her family, together with all White families, are wholly structured on an “uneven playing field.”

I feel that Debby’s decades-long odyssey rises to the level of a heroic journey in part because of the revolutionary impact it made on her entire being. Her discovery at age 48 isn’t comparable to figuring out how to work the car radio pre-sets. Uncovering racial injustice buried in her fundamental being left Debby entirely disoriented. It was physical. “Just a year after that first Wheelock class, little in my life felt the same anymore. I woke up every day feeling lost and afraid. I experienced bouts of dizziness and waves of nausea that could be stopped only by sitting and hanging my head between my knees. I kept a bottle of ginger ale with me at all times to quell the nausea.”[7]

One of the first changes following Debby’s awakening to her whiteness was her eagerness to speak unguardedly about race. Through her arts and teaching years, sprinkled with diversity workshops, Debbie was hyper-vigilant about her speech. The careful communication, she would discover, was to maintain her image as a racially enlightened person who would never offend or slip unknowingly into racist phraseology. After Wheelock, Debbie found the courage to be transparent with her genuine feelings, even if she thought that they would anger or offend those listening to her. She reported that her Black friends were noticeably more relaxed in Debby’s presence, knowing that she was speaking with a frankness that acknowledged her own role in the racial divide.

Waking Up White

My hunch is that the ultimate fruit of Debby’s journey and her Wheelock rebirth is the book itself. Waking Up White beckons middle class readers who may be generations away from explicit racist attitudes, to reassess how their lives nevertheless benefit from social unfairness. The oft-repeated expression about being “born on third base and thinking you hit a triple,” can be taken to heart by every White reader.

Debbie tells the story of each of her parents’ deaths, her mother’s when she was 34 and her father’s much later. The episodes are poignant. Each died amid evidences that they carried deep regret. Debby’s father ended his life with a sad sense that, despite his success, he didn’t do enough for others.

As I read these tender stories, I felt that Debby’s journey was the very quest that her parents could not take. She needed to shake off her privilege or at least acknowledge it. She needed to move beyond Winchester, which seemed to be the ultimate destination. Debby needed to face and be embraced by the very people who suffer so that Winchester and Debby’s childhood life was possible.

What Am I Learning?

Waking Up White consists of two levels.

First it overflows with stories, which reveal the daily plight of Blacks in America.

Second, the book is the story of Debby’s personal quest, her journey.

What she learns about Blacks and relates in the first level is an outgrowth of what she learned about herself as she journeyed.

To take my own journey is the book’s invitation. Getting engaged with people of color, having hands in efforts for justice, daring to listen and talk frankly with people different from me, and then embracing the ways that these efforts make me different is the elixir that heals.

The last chapter, “Tell Me What to Do” is amazingly unsatisfying. Here it is in its entirety:

The good news is that everyone can do something to loosen racism’s hold on America. The bad news is that unless you set yourself up for success, trying to do something helpful can actually perpetuate racism. Take time to learn and engage with the problem in order to lower the chances of making the same mistakes I did.

I take this to mean that reading books, attending diversity programs, contributing to time worn charitable efforts will never end racism in America. We only become a different country when we are willing to take the journey to become different people.

_______________

[1] Irving, Debby. Waking Up White: and Finding Myself in the Story of Race (Kindle Location 994). Elephant Room Press. Kindle Edition.

[2] Ibid. Locations 1787-1788.

[3] Ibid. Locations 1820-1822.

[4] Ibid. Locations 2384-2386.

[5] Ibid. Locations 2397-2398.

[6] Ibid. Locations 593-595.

[7] Ibid. Locations 2830-2832.