Act and Consequence as a Creational Principle that Pervades the Old Testament

I got my used copy of Anderson’s book through Amazon. When the out of print paperback arrived it bore the stamp of the Westhill College library inside the front cover. Evidently, the librarians at Westhill College had pulled it off the shelves and contributed it to the used book market.

Despite this unceremonious treatment, the book’s essay’s sparkle with insight. And Schmid’s essay was worth my time to read and ponder.

What I’ve written here is my attempt to preserve and restate Schmid’s central ideas.

Act and Consequence

The core of Schmid’s essay is the connection between act and consequence. The Old Testament’s human writers saw the world as a place governed by predictable causes and effects. A modern reader might jump to the conclusion that we’re talking about the principles of physics or natural law—billiard balls bumping each other. I would say that this comparison is a good start. What the ancients saw were predictable causes and effects, much like physics laws, which went beyond the material world. Act and Consequence is like billiard ball physics in the moral and spiritual realms. What a society values and how it treats its weak members could be relied upon to stimulate an answering response.

Jeremiah 4 gives an example of this interrelationship between the moral and physical world. The fourth chapter begins with the prophet’s lament over his people’s worship of strange deities. He then announces a coming political consequence, which will take the form of Babylonian armies overrunning Judah. The people’s moral and religious malfeasance results in geo-political catastrophe.

The consequence of Israel’s false worship doesn’t stop with military defeat. The people’s waywardness affects the land itself:

it was formless and empty;

and at the heavens,

and their light was gone.

I looked at the mountains,

and they were quaking;

All the hills were swaying.

I looked, and there were no people;

every bird in the sky had flown away.

I looked, and the fruitful land was a desert;

all its towns lay in ruins

before the Lord, before his fierce anger.

The prophet directs his people’s gaze to environmental catastrophe. So, the people’s worship of false gods sets into motion bad consequences that flow into what we would see as an unrelated area, namely the realm of nature.

The Little Community of Creation

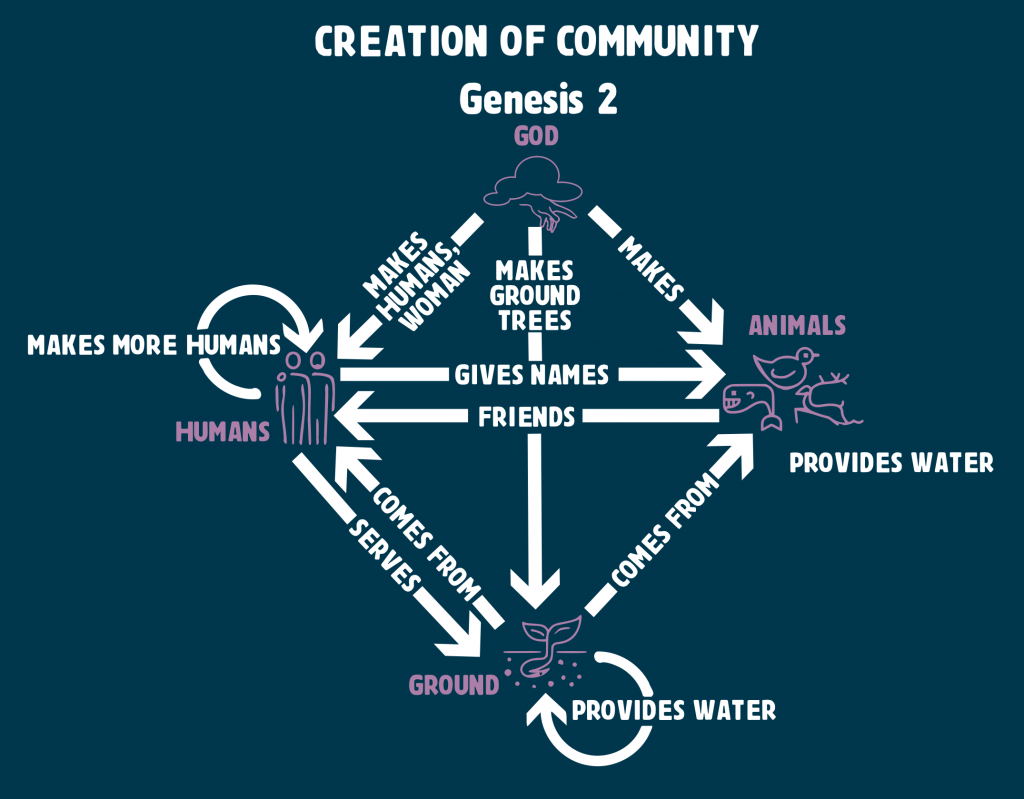

In the second creation story in Genesis 2, the Creator organizes a little community. This community’s members are the people, the animals, the Creator, and the ground. Each of the characters handles and benefits from each of the other members.

For example, humans serve or till the ground and name the animals. Before God sets up these responsibilities, he draws humans and animals out of the ground. God gives the animals as humanity’s companions.

An important trait of this community is relationships. God’s setting up of relationships in Genesis 2 is more the story’s point than giving information on how the Universe got its start. Genesis 2 is focused on the setup of relationships.

God Built Act and Consequence into the Created Order

When God made the world, or better, when God organized the world, he built interrelationships between himself, people, animals, and the earth. These characters are bound in mutual purposefulness and regular patterns of influence. They are like a mobile where the movement of one element stimulates movement in the other elements.

As Genesis moves into the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, it tells of a disturbance in the community and its consequences. In turn, this disobedience, eating the forbidden fruit, influences each of the other community members. The eating of the fruit at the serpent’s behest results in cracks in the relationship between the man and woman, the humans and God, and the humans and the serpent.

The consequence of the disobedience continues in the judgment section where the serpent is destined to crawl on the ground, the woman suffers difficulty in childbirth, and the man struggles in farming the land.

The reader will notice that each of these consequences is a rollback of the creational order that God just organized. For example, the Garden of Eden gave Adam and Eve a comfortable life where food was easy to obtain. We might say that God designed human life to be comfortable and prosperous. Now the disobedience has ushered in a deterioration of living conditions and the soil is no longer cooperative. At first, God commissions the woman as co-creator with Godself to bring more people into the world. But now, childbearing is difficult.

Does God Send or Allow Judgment to Fall on the World?

The text at this point confronts the reader with a problem. Has God sent these consequences for disobedience as punishments or are they natural consequences? Admittedly, the text plainly attributes to God responsibility for the new difficulty: “I will put enmity… I will greatly increase your pangs…” and so on. This reading has the advantage of conforming superficially to the explicit wording of the text.

I nevertheless favor the “natural consequences” idea because it avoids the problem of seeing God letting human malfeasance force him into undo the very order of creation what he has just established.

On the other hand, if readers see Adam and Eve’s distrust, distancing, and disobedience as a force rippling predictably through an interrelated creation, which God set up and sustains, they might say that God is judging the situation by letting this happen.

I’d like to substantiate these thoughts with a few of Terence Fretheim’s observations in his book, God and World: A Relational Theology of Creation:

The most common agent of divine judgment is the created moral order. That is, God has created the world in such a way that deeds (whether good or evil) will have consequences. Generally speaking, the relationship between deed and consequence is conceived in intrinsic rather than extrinsic terms. That is to say, the consequences grow out of the deed itself; they are not a penalty (or reward) introduced by God into the situation. That good deeds have consequences may be called blessing; that sins have consequences may be called judgment…How is God involved in the move from sin to consequence?… But, generally speaking, judgment is not something that God introduces into the sinful situation, such as imposing a penalty specified in the law; rather, God mediates the consequences that are intrinsic to the wickedness itself.1

Schmid’s Essay

None of my explanation of the Act-Consequence Principle is part of Schmid’s essay. He writes for fellow scholars and appears to assume that they know what the Act-Consequence Principle is.

What Schmid does lay out explicitly is the idea that the Act-Consequence Principle underlies most of the major literary segments of the Old Testament.

Here’s the list of the literature he mentions explicitly:

- The Legal Code (Holiness Code)

- Preexilic prophets (the pre-Assyrian prophets Jonah, Amos, Hosea, Micah, and Isaiah, and the pre-Babylonian prophets Nahum, Zephaniah, Habakkuk, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel)

- Deuteronomistic History (Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuels and Kings)

- Primeval History (Genesis 1-12)

- Ancestral History (Genesis 12-50)

- Wisdom Literature

Schmid’s aim is to show how the creational Act Consequence Principle pervades the Old Testament. The foundation supporting these differing literatures is a confidence that behaviors set into motion regular patterns of results. Because this is true, it follows that creation is ever-present throughout the Bible and more important than Christians and their biblical theologians have assumed.

The Primeval History

Predictable consequences echoing around the humanity-animal-ground-God community continue to animate the stories that follow the sin and judgment in the Garden story in Genesis 3. Cain murders his brother Abel and tries to hide the evil deed. But God at once knows what Cain has done because the ground itself refuses to hide the act or remain silent. Again, the principle is that a stimulus in one area of the created order prompts reaction in another.

The Cain and Able Story

For Cain to kill Abel and send his blood into the ground, from which God brought humanity forth, is an act of rolling creation backwards. Recall in Genesis 2 that God could not bring plants into the world until there was a human to till the earth. Cain’s treachery sends another human down to the ground, which is now unproductive. What’s more, Cain finds himself alienated from God.

The Deuteronomistic History

Early in the essay he mentions the Deuteronomic instructions for dealing with a murdered person whose assailant has disappeared. This citation is gloriously successful in showing how orderly inter-relationships govern even the social world in the mind of the Deuteronomist.

Dealing with the Crime of Murder

5Then the priests, the sons of Levi, shall come forward, for the Lord your God has chosen them to minister to him and to pronounce blessings in the name of the Lord, and by their decision all cases of dispute and assault shall be settled. 6All the elders of that town nearest the body shall wash their hands over the heifer whose neck was broken in the wadi, 7and they shall declare: ‘Our hands did not shed this blood, nor were we witnesses to it. 8Absolve, O Lord, your people Israel, whom you redeemed; do not let the guilt of innocent blood remain in the midst of your people Israel.’ Then they will be absolved of blood-guilt. 9So you shall purge the guilt of innocent blood from your midst, because you must do what is right in the sight of the Lord.

These instructions seem primitive and misguided in our estimation. But they make clear that the ancients saw their world as controlled by principles of fairness which fixes wrongs by an almost mechanical remediation process. Again, God built orderliness into all things, including the towns and network of relationships where murders took place.

The Prophets

Schmid moves on to consider the “pre-exilic” prophets. The Act-Consequence principle certainly informed these thinkers’ pronouncements. Put differently, the prophets assumed that morality was built-in to the created world. This creational morality was the standard by which the prophets measured their society’s level of health and righteousness.

Schmid claims that the pre-exilic prophets don’t make appeal to Mosaic Law, which is connected to Israel’s deliverance from Egypt.

As Schmid’s idea here began to take root in my imagination, I spent some time skimming through the Book of Amos. Immediately in the first two chapters the prophet offers oracles of judgment on the peoples who were Israel and Judah’s neighbors. This is significant because God had not given the Mosaic Law, written or oral, to any peoples other than Israel. We can infer that the prophet is pronouncing judgment on all peoples by reference to a universal standard—the moral code built into the world.

Ancestral History

In the Ancestral History, Schmid recalls the story, recorded in Genesis 12, when a famine forced Abram and Sarai to go to Egypt. Because Sarai is beautiful, Abram plots with her to deceive the Pharoah. The plan is to lie and say that she and Abram are brother and sister. If they presented themselves as a married couple the Pharaoh would have killed Abram to take Sarai for himself. But thinking Abram was her brother, the Pharaoh showers Abram with gifts and takes Sarai into his house. This deception and violation of marriage integrity prompts a plague, as the ancients might expect because of the operation of the Act-Consequence principle. To remedy the problem the Pharaoh restores Sarai to Abraham her husband and orders the couple out of Egypt.

Ironically, Pharaoh lectures Abraham on his lack of morality and then organizes the correction to the imbalance. The Pharaoh, though not in the bubble of Abrahamic blessing, understands, as we would say, how the world works. The world’s moral structure, which links act and consequence, is familiar throughout the entire world.

Wisdom

We’ll cite one final example, namely the wisdom tradition. The Wisdom Books include Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes.

by understanding he established the heavens;

20 by his knowledge the deeps broke open,

and the clouds drop down the dew.

21 My child, do not let these escape from your sight:

keep sound wisdom and prudence,

22 and they will be life for your soul

and adornment for your neck.

23 Then you will walk on your way securely

and your foot will not stumble.

24 If you sit down, you will not be afraid;

when you lie down, your sleep will be sweet.

25 Do not be afraid of sudden panic,

or of the storm that strikes the wicked;

26 for the Lord will be your confidence

and will keep your foot from being caught.

Notice the act-consequence sequence. If the ancient student will cultivate Wisdom, which is a rich concept in this and other contexts, then generalized good fortune will follow. It’s as if Wisdom is a secret sauce that the Creator pours into the world liberally. The result is not dead stuff that God has arranged.

Wisdom enlivens existence. It rewards those who pay attention to it and pattern their actions by its principles. To read Proverbs is to see the Act-Consequence principle over and over. Do this and happiness, health, good reputation, and long life will follow. Do the opposite and misfortune, sickness, and infertility will hamper your steps.

Summary

Towards the end of his essay, Schmid summarizes with this statement:

In other posts on this website, I’ve talked about continuing creation. In contrast to originating creation, continuing creation means that God has never stopped creating even after creation’s 7th day when God rested (Genesis 2.2). So, at important milestones in the Old Testament story, say at the rescue at the Red Sea, the reader gets textual hints that God is not only redeeming but also creating.

In Moses’ Song in Exodus 15, which celebrates God’s rescue by pushing the waters aside so that the Israelites can get away from Pharaoh’s chariots, we get a little allusion to the creation story:

From Moses’ Song

the floods stood up in a heap;

In other words, the forming of the world by bringing order to chaos is still happening.

I bring up continuing creation as a contrast to what Schmid has given us. Schmid’s essay says that the creation that encompasses our being today bears the character of the creation that came into being at the beginning of Genesis. There’s an inner structure to the world around us. It predictably feeds back in kind what people enact in it.

A Random Adage from Proverbs

whoever rebukes the wicked gets hurt.

8 A scoffer who is rebuked will only hate you;

the wise, when rebuked, will love you.

9 Give instruction to the wise, and they will become wiser still;

teach the righteous and they will gain in learning.

Schmid is saying that we can live better lives when we condition our behaviors and work to build in properties of the created world.

We never leave Creation behind. God created the world back then when God gave everything its start. And God continued to create. And each new day we see the traces of the original beauty and goodness and generosity continuing predictably.

The subtitle of Schmid’s essay grabbed my attention: “Creation Theology is the Broad Horizon of Biblical Theology.” Somehow “broad horizon” is what one sees when they climb the highest mountain on an island and behold a 365 degree continuous strip of blue ocean defining the limits of vision. Transferred to faith, creation is everywhere.

As climate catastrophe, artificial intelligence, and political upheaval threaten to roll back the created order and usher into the world a resurgence of chaos, biblical people can know that God’s creational presence is ever at work bringing, not only redemption, but also newness to all things.

- Fretheim, Terence E., God and World in the Old Testament: A Relational Theology of Creation. Abingdon Press. Kindle Edition. References found in the “Divine Judgment” subsection of the sixth chapter, “Creation, Judgment and Salvation in the Prophets.” ↩︎