I. Conversion in Retrospect: Talking About Conversion

Introduction

Six miles from my church stands a large church building which houses an equally large Presbyterian congregation. Its membership is three times ours. As I was organizing the adult class project, described later in this report, I phoned one of the pastors of this large Presbyterian congregation. I wanted from him the name of one of his congregants who could attend our first class session and share an account of his or her experience of religious conversion. Hearing this request, the pastor was silent for several seconds. “No one comes to mind,” he finally replied. “I could try to rearrange my schedule and come myself…”

The phone conversation continued for twenty minutes. In that time the pastor could not recall a single parishioner from his church who might have been able to share a conversion experience.

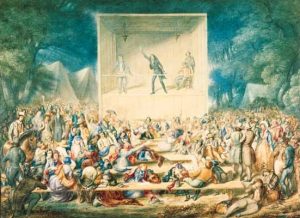

This little exchange became more significant in my mind when in the fourth class session I asked the twenty-two member group how many of them had, at some time, walked forward in response to an “altar call” or similar evangelistic invitation. Ten hands went up. Admittedly, most of these “conversions” the group told me were under social pressure from parents or zealous ministers. Nevertheless, many in my class had personal experience with the revivalistic tradition.

More significantly, as the course progressed, it became clear that most participants had enjoyed a rich personal tapestry of encounters with God. We heard stories of experiences that I would certainly describe as “conversions.” Class members described prayers answered and not answered. They spoke of pilgrimages from one congregation to another, seasons of spiritual dryness, sojourns in the far country, and even “dark nights of the soul.”

The apparent difference in the two congregations’ spiritual depth becomes increasingly curious when I consider that they are–except for size–much alike in theology, sociology, and leadership. Why then could I locate several conversions in a twenty-two member group while my peer could not remember one among a thousand Presbyterians?

Because I asked.

In other words, the seeming scarcity of personal encounters with God in the larger congregation is a function of the conversation among its members. It is not a result of spiritual shallowness or pastoral ineptness. The minister and members may not have created many occasions to share with one another their experiences with God. As Coalter, Mulder, and Weeks have written recently:

Protestants still have profound experiences of God’s grace and presence. However, congregations frequently inhibit discussion of such depth encounters because they are considered too private or too personal to be held in common.[i]

TALKING ABOUT SPIRITUAL ENCOUNTER

Reluctance to talk about conversion in many Presbyterian Churches is rooted in our more general reluctance to speak of any sort of spiritual encounter. Decision-making groups like Presbyterian sessions typically rely far more on business insights than prayer for guidance in directing a church’s affairs. Congregations choose elders with an eye for their business acumen. This results in leadership dedicated to efficiency and institutional success with little reference to God’s guidance. Business-like leadership, of course, is not inherently nonspiritual. My concern rather is with churches’ uncritical and extensive reliance on secular techniques and values.

This reliance sets a tone which ripples throughout the church’s program. When a congregation’s core leadership, including pastors, is not relating the Scriptures and theological tradition (not to mention its sense of the Spirit’s urges) to its routine decisions, then the congregation’s spiritual vitality will suffer. “Recruiting volunteers” replaces hearing God’s summons to service. Survival goals replace a vision for participating in Christ’s contemporary ministry. “Fund raising” replaces stewardship of gifts. Shorn of its spiritual vocabulary, church leadership negotiates the up-building of the congregation in terms belonging to a realm essentially unlike itself. God’s encounter with God’s people in turn becomes a church’s silent reality rather than its central joy.

Secular values have similarly shaped our practice of pastoral care. Most of my pastoral conversations, especially in formal counselling sessions, do not ponder God’s activity in a parishioner’s life. Only infrequently through much of my ministry have I talked in pastoral conversations about providence, guidance, vocation, or Christian ethics, which are all crucial for anyone concerned to live as Christ’s disciple. My language in pastoral care has been that of the therapist. It has seemed to me useful to draw on the insights and vocabulary of Transactional Analysis, Gestalt techniques, or Family Systems therapy in helping struggling parishioners. This easy borrowing of popular psychological language displaces opportunity to relate God’s presence to a real, complex situation. Instead of supporting laypeople in articulating and interpreting their relationship with God–the prime occasion to develop faith maturity–I have offered help in the language of the therapeutic world. Eugene Peterson speaks of the contemporary pastor’s abandonment of the faith’s resources in his or her work of nurture:

…When I get up on Monday to face a week of parish routine I am handed books by Sigmund Freud and Abraham Maslow, Marshall McLuhan and Talcott Parsons, John Kenneth Galbraith and Lewis Mumford. It is a literature of humanism and technology. The pulpit is grounded in the prophetic and kerygmatic traditions but the church office is organized around IBM machines. The act of teaching is honed on biblical insights derived from historical, grammatical, form, and redaction criticism while the hospital visit is shaped under the supervision of psychiatrists and physicians.[iii]

The Breakdown of Natural Community

I have suggested thus far that Presbyterians and Mainline Protestants are not only reticent in discussing their experience with conversion, but also in expressing to one another details of their relationship with God. Both kinds of witness–the former a sub-category of the latter–have profound impact on the congregation’s nurture of faith in individual believers. This impact we will discuss throughout this report.

Before we turn to this in earnest, it is important to understand one more influence which decreases congregational conversation in liberal Protestant churches; namely, the general loneliness in Western societies. The society-wide breakdown in natural community has had an erosive effect on congregational closeness. It has been lamented by thinkers from M. Scott Peck[iv] to Roberta Hestenes of Eastern Baptist College[v] to Wade Clark Roof and William McKinney.[vi] If Presbyterians are not present with one another; don’t know one another’s names, families, and work; if our programs discourage talking, then we will certainly not be sharing the tender details of our prayer lives. In mentioning community fragmentation and the loneliness that results, I’ve opened up a vast and well-studied field. Included in this trend are the changes in family structure, nuclear and extended; work place upheaval and alienation; and anonymous neighborhoods. Much of this is unrelated to the climate of sharing in churches. Some factors, however, do touch us within the church.

The main culprits in my experience include the following. First, high mobility and affluence which have many Presbyterians traveling on weekends. Second, is the more profound mobility of residence relocation. Great numbers of Americans changing their homes for business opportunity or recreation proclaims that relationships are of less importance than success and prosperity. Finally, divorce is a factor in congregational intimacy. While divorce and the spiritual journey that accompanies it sometimes brings new members into our congregations, more often one or both partners in a dissolved marriage leave our fellowship.

I mention these cultural factors not to suggest, because community is declining in American culture, that therefore we don’t talk about religious experience in church. Rather, I mention them to recognize that when natural community breaks down we simply are left with fewer opportunities to be close in church fellowship.

To illustrate: as I planned the adult class on conversion which I’ll later describe, I asked potential members to commit to being present for each of eight sessions. Many were unable to promise such attendance due to Sunday work, vacations, or out-of-town family visits. So, even for Presbyterians committed to talking about conversion, the factors which erode community in general also cut down opportunities to share spiritual things.

WHY MAINLINE PROTESTANTS DON’T DISCUSS SPIRITUAL EXPERIENCE

We turn now to examining factors within the church which erode our ability and willingness to discuss our spiritual experiences.

Protestant Scholasticism

For Presbyterians, the Scholastic tradition is retained in several of the historical confessions which compose the Presbyterian Book of Confessions. Less formally, this tradition’s spirit is alive wherever the so-called Princeton Theology retains influence in America. The Princeton Theology is commonly associated with the 19th century leadership of Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge, A. A. Hodge, and Benjamin B. Warfield–all Princeton Theological Seminary professors. These influential systemitizers sent into Presbyterian pulpits and schools thousands of adherents. Even today such seminaries as Westminster of Philadelphia, Covenant of St. Louis, Reformed of Jackson, Mississippi, together with individual professors like Roger Nicole of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary or John Gerstner of Pittsburgh Seminary maintain the spirit of Protestant Scholasticism.[vii]

This systematizing impulse, with its long tradition in Reformed Churches, has served to articulate the faith’s precise nature. Unfortunately, at times it has replaced faith’s relational character with an arid orthodoxy. Rationalism in theology fosters both intellectual formalism and religious complacency. In response, some Presbyterians have looked for a warmer, more experiential piety such as that of the revivalistic traditions.[viii] The interplay between these poles crops up throughout Presbyterian history. Says Edith Blumhofer:

Throughout American Presbyterian history debates about evangelism helped focus deeply divisive issues that occasionally led to schism as Presbyterians faced the tension between intellect and emotion, Calvinism and revivalism.[ix]

The strong presence of the intellectual or propositional facet of the Gospel has become something of a family characteristic in the Presbyterian household. We honor intellection because of the centrality of God’s Word in our theology. But sometimes our honoring of God with our minds eclipses the relational dimension of faith. Thus, ordaining presbyteries test ministerial candidates for orthodoxy, not prayer. Presbyterians comfortably produce exegetes, theologians, and social prophets. Other groups lead the way in evangelism and spirituality. This is not to say that conversation about one’s encounter with God is explicitly forbidden. It is not. However, in Presbyterian circles such sharing feels less significant than talk which articulates precise theological positions logically and biblically.

One recent event in the life of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) will illustrate this. During the first months of 1994, the denomination was embroiled in controversy concerning the ecumenical Re-Imagining Conference which met in Minneapolis in November, 1993 and which, put simply, explored ways that the Christian understanding of God could be expressed in less masculine and culture-bound images. For Presbyterians, it was second nature to approach such questions theologically, defining the borders of orthodoxy through biblical exegesis, church history, the history of doctrine, social analysis, and so on.

As the denomination’s June General Assembly meeting neared, the time when Presbyterians could officially respond to the conference, congregations and pastors were showered with articles and position papers on the controversy. The field of battle seemed to be in the realm of ideas. This pre-General Assembly debating eclipsed any thought that spiritual discernment or reconciliation might be resources for finding our way through the crisis. It is difficult for us to imagine that our General Assembly would resolve this difficulty in the way that the Society of Friends, gathered in 1758, yielded to John Woolman’s inspiration concerning slavery.

As it turned out, the crisis was resolved at the annual meeting by a sensible compromise which felt more like a moment of grace than a discovery of the right idea. Following the near-unanimous vote in favor of the reconciling compromise, observers reported that ideological foes spontaneously sang and hugged one another. The crisis was solved through love and reconciliation, not theological precision. The point of this story has to do with the unexpectedness of the grace-filled resolution. It was this non-intellectual solution that the Presbyterians did not seem to foresee.

The attempt here is not to suggest that emotional ardor or even charismatic excitement are absent in Presbyterian churches. Classic controversies such as the Old Side-New Side struggle in Colonial America demonstrate that emotional fervor and spiritual awakening also exist within Presbyterian experience. Certainly emotion and volition join intellection in Presbyterian congregational life today. My desire here, however, is to point out a Presbyterian habit of leading with the mind. We have defined and defended beliefs for our entire history. Presbyterians dwell comfortably in the world of ideas. Intellection comes naturally and spiritual experience feels less significant or even suspect by comparison.

Secularization

The term, “secularization,” refers to the profound shift in Western attitudes, values, and beliefs which has been underway at least since the Enlightenment. At that time–the 17th century–thinkers greatly expanded empirical inquiry and reason as the means for uncovering truth about the physical universe. In the following century, the scientific outlook came to be applied to sociology, politics, and even ethics.[x] One driving force behind advancing secularization is the impressive improvements in life quality which scientific method has brought about. The Twentieth Century has witnessed a steady march of technical achievements which have left the claims and promise of Christianity standing idly aside. The pace of innovation wrought by human ingenuity has, of late, only been exceeded by the general and uncritical optimism that technology will ultimately solve every problem.

It was against this intellectual background that the ideological underpinnings of constitutional government in the United States were established. This is not to say that the United States is entirely a product of the Enlightenment. Prior to the constitutional period, settlers in America, deeply influenced by the Protestant Reformation, attempted to realize a vision of this land as having a divine commission in the world.[xi] In many respects, that vision of America as a Christian nation still lives. Robert Wuthnow in his The Restructuring of American Religion, speaks of competing religious dreams of America. So, America’s rich religious heritage is still part of our understanding of our own essence.

Despite the persistence of the religious character in this culture, the long process of secularization has broken down what once was a comprehensive social consensus that a Christian world view and ethic would dominate American thought. At one time, Christianity sustained American culture, ethics, education, and even economic life. Today, significant sectors of our culture rest on different ideological foundations. Ahlstrom has called the late 20th century, “Post-Puritan America.”[xii] By this expression he means that the ideological consensus which at one time undergirded American culture has significantly eroded.

Consequently, secularization functions to provide an array of alternative choices and explanations in all areas of American life. The rise of science in this century, for instance, “explains” a whole range of phenomena from the Universe’s birth to the origin of human beings. Christianity no longer dominates the conversation about such origins. Secularization has suggested that ethical decision-making need not appeal to Christian values to find correct or appropriate courses of behavior. As a result, Christian faith in America does not enjoy the support of public schools in leading children in prayer or developing their Christian character. Churches can no longer count on businesses or other organizations to accommodate their schedules so not to interfere with worship attendance.

In accordance with its unique history, the United States has experienced secularization in a distinctly American way. Martin Marty has shown that secularization has proceeded differently in America than on the European continent or in England.[xiii] In Europe, academicians and social thinkers have attacked Christian faith overtly. In England, intellectuals simply have ignored religion. In America, secularization and religious values co-exist. On one hand, significant numbers of people continue to adhere to inherited beliefs. On the other, secular thinking predominates in many spheres, leaving Christianity to appear less adequate to guide and inform. Thus, government, education, psycho-therapeutic thinking, business, sociology, not to mention the natural sciences are all conducted with little or no reference to Christian faith.

This ironic juxtaposition of advanced secularization and unparalleled church attendance has impact on church life. Untold millions of Americans work all week in businesses, education, or government where secular thinking predominates. This mode of thought does not change when believers go to church on Sunday. Small wonder–as we have observed–that the church governing board is dominated by business techniques and pastoral care is informed by psychological theory. Secularization, in other words, influences the kinds of thinking which laypeople, as well as clergy, understand and revere, even in church.

Secularization has particular impact on Presbyterians. Christians in sectarian traditions have often greeted modern thinking with suspicion. We have been much less defensive. In fact, Presbyterians have tended to feel the full impact of secularization because of our historic openness to new modes of thought. This openness is rooted in the Reformation. It is of no small significance that Calvin and Zwingli were educated in the humanist traditions of their time. In turn, Calvinists tend to see rigorous thinking as a mode of serving God. Such a tradition prevents Presbyterians from blunting by authoritative fiat secularization’s intellectual challenges. Confidence that no genuine intellectual development threatens to dislodge the Gospel’s truth, disposes Presbyterians to an openness to all new ideas. While this keeps Presbyterianism current and flexible in changing times, it also imposes the intellectual burden of continually re-thinking our theology in light of new understandings. Not surprisingly, some new ideas may not be comfortably incorporated into the thinking and teaching of our churches.

The impact of secularization on Presbyterians goes beyond our practice of accommodating to shifts and advances in thinking. Presbyterians, along with other liberal Christian groups, have even appropriated the techniques and insights of the empirical sciences in the service of the church. The historical-critical movement in biblical exegesis or the innovations in pastoral care and counseling are examples of how we have benefited from the free borrowing of scientific thought modes for Christian purposes.

A further complexity in the secularization process is the popular impression that science and religion are essentially in conflict. Says Diogenes Allen:

For many people science stands for rationality, evidence, knowledge, enlightenment. Religion, in contrast, stands for backwardness, conservatism, superstition, authoritarianism, and is regarded as the enemy and rival of science. These are extreme characterizations, but however much the extremes are toned down, the general impression is that some hostility, some incompatibility, some rivalry between religion and science exists.[xiv]

Allen goes on to challenge this assumption, asserting that science and Christianity are in “deep harmony.”[xv] Nevertheless, it is a commonplace in secularized America that the approach and thought patterns of the scientific world view yield better, more practical knowledge and that talk of faith or religious experience inhabits a lower tier of truthfulness and usefulness.

I have long observed Presbyterians–ministers and laypeople–moving from one psychological, organizational, or intellectual fashion to the next. In my college days the Transactional Analysis movement influenced untold numbers of ministers and laypeople. Later, came the assertiveness and “burn-out” psychologies. Later still, came family systems thinking and the insights of those who deal with addictive disorders.

Our wandering from one emerging fad in the social sciences to the next betrays where Presbyterians look for personal healing and inspiration. It is a clue to the degree that secular schemes, bearing the authority of scientific validation, impress us.

Typical congregations, bouncing from one promising trend to the next, loose appreciation for religious thought in general and religious experience in particular. To speak in a Presbyterian church of one’s prayer life, sense of God’s presence, conversion, or other spiritual encounter is to risk the embarrassment of being thought naive or sentimental.

Privatization

When Jesus called disciples into communion with himself–the essence of Christian faith–he also called them into community with one another. This was no innovation. The biblical vision of relatedness with God, from the call of Israel to the establishment of the early church, envisioned faith thriving in the context of a society of believers.

This connection between faith and community has been fundamentally ruptured in America today. Some thinkers even talk of a “churchless Christianity” emerging in our culture. Roof and McKinny report that

the overwhelming majority of the population–inside and outside the churches–holds to strongly individualistic views on religion. In a Gallup poll in 1978, a staggering 81 percent of the respondents agreed with the statement, ‘An individual should arrive at his or her own religious beliefs independent of any churches or synagogues.’ Seventy-eight percent (and 70 percent of churchgoers) said that one can be a ‘good’ Christian or Jew without attending church or synagogue.[xvi]

The sweeping devaluation of Christian community–and community in general in our culture–affects the climate of intimacy in our congregations. When congregational life is widely seen as an expendable extra, Christians do not look to their churches not as a wellspring of personal support and unqualified acceptance. Instead, the church is perceived as a dispensary of programs, inspiration, and social contacts. In turn, the amount of investment churchgoers are willing to make in community building is minimized. Thus, for untold numbers of mainline Protestant congregations, the intimacy necessary to discuss members’ inner spiritual lives seems less appropriate in church than in, say, the context of a support group or a close friendship. In order to speak of God’s grace, a word is necessary about what in life needs grace, namely our brokenness and personal failings. Talk about spiritual journey entails admitting to the part of life which needs to be left behind. Witness to religious conversion entails admission that transformation is necessary and that community is necessary to transformation. Such self-disclosure seems unnecessary, even inappropriate, in church.

The sources of this heightened individualism and privatization of faith are complex. Certainly the traditional disestablishment of religion in America is a starting point. The constitutional guarantee that a person’s religious practice is both voluntary and separated from government interference has lodged the locus of religious authority in the individual. More recently, even America’s informal assumption that Christianity has suffered erosion. We are, according to some observers in the midst of a shift away from the “Christendom Paradigm.”[xvii] No longer does Christian faith literally, go with the territory. No longer does the Church enjoy–even in subtle forms–the endorsement, protection, or coercion of the state.

This shift, in turn, both liberates and tempts the individual believer. It liberates the individual from all establishment coercion in the choice whether and where to go to church. It tempts people, however, to see themselves as the critics and consumers of religious services rather than vital members of transforming fellowship. This trend of making the individual responsible for his or her religious faith has accelerated since the 1960’s when social control exerted by families, towns, and traditions has diminished.

Shorn of most community or public endorsement, religion in America can easily be construed as without public importance.[xviii] As such it has come to occupy the private realm rather than the more revered public realm–the so-called “real world.” In this mind set, faith pertains to one’s inner life rather than one’s entire life. Says Nelson:

The type of privacy into which American religion has drifted is more likely to be one of self-fulfillment: authority is not in God, who comes into a person’s life with a mission; it is rooted in a person’s psychological needs…The search is not for truth about God but for religious beliefs and practices that help people cope with inner difficulties…This idea of religion’s becoming sacred only to oneself is startling, but not too far fetched if we understand how religious authority has shifted, from a conception of God who reveals God’s will for the world, to individuals who are concerned primarily for themselves.[xix]

Even for Presbyterians–a group traditionally committed to the transformation of culture–matters of faith take their place in the constellation of private convictions. As such, belief resides in the bedroom of life together with the intimacies of relationships, health concerns, money, and political views.

Finally, the privatization and voluntary character of American Religion, Presbyterianism included, seduces laity and clergy alike to understand church belonging as a form of consumption. Marketing terms such as church “shoppers” or “market share” fix in our minds the idea that religious participation resembles a consumer event rather than a relational commitment. The transaction in this marketing mentality is an exchange of religious services for contributions, volunteering, and attendance. Should the services prove inadequate, the religious consumer can take his or her business to one of a variety of eager, competing churches. In this model, church staffs and lay leaders treat parishioners like customers to be wooed. The customer is always right. Accordingly, concepts such as church authority or discipline are wholly out of place.

The movement of faith out of the public sphere into the realm of a person’s private business has left religious experience as one of those things too personal to talk about. As such, it becomes part of peoples’ hidden selves which is covered by the roles and masks of their public selves. Daily, pastors in mainline churches encounter clues about the private reality of parishioners’ faith. One is the fearfulness laypeople have in offering extemporaneous prayers in meetings. Another is the embarrassment congregants experience over their ignorance of religious things. Still another is the reluctance churchgoers have in sharing honest doubts or moral struggles with one another.

The following situation illustrates how the private and voluntary nature of faith in Presbyterian circles has impact on congregational intimacy.

In my congregation a young, upscale family of five recently left our church, ostensibly because we didn’t have a strong youth program. I telephoned the mother of the household who gleefully declared that their thirteen year old had “found” their new church–a large Southern Baptist Congregation. Apparently, this daughter had been attending the Baptist’s youth fellowship meetings with friends and, on that basis, the family decided to begin attending worship in that congregation.

Absent from this decision was explicit consideration of theology, relationships with other congregants, other programing, or sense of call to ministry in that particular fellowship. It appears that the twin decisions to leave one community and unite with another were reached much as a dry cleaning company or car rental agency are chosen. As such, it was not beyond a thirteen year old’s ability to choose for the entire family.

Implicit in this consumer mode of making such decisions is a devaluing of congregational relationships. When congregants’ bedrock criterion for participation in church fellowship is perceived personal benefit, rather than a matrix of relationships including the relationship with Christ, then congregational intimacy suffers.

I’m fairly certain that, had this family stayed in our congregation, a very rich dialogue would have developed. I say this because I enjoyed a warm relationship with the father of the household. He was, and is, a skilled business person with exceptional “people skills.” In our congregation, he gravitated to leadership on the session and served for a year as chairperson of our Worship Committee.

Late one evening following a meeting, he and I found ourselves alone in my office–too tired to go home. He began talking about what he really thought of Christian faith. His self-disclosure jolted me because he announced that he totally disbelieved in any transcendent element in the faith.

Why did he come to church? I wondered aloud. He responded with a complicated answer which had to do with participating in our culture’s rituals and intellectual underpinnings. His theology was similar to that of the death of God theologians, minus the emphasis on theodicy.

This conversation was the only sharing of any depth which I experienced with any member of that household. In the quiet of my office I found myself trying to articulate for both of us why I believed in God. At the same time, I wondered silently if there were deeper reasons why this young corporate executive and family man gravitated to a church and gave himself generously to its affairs.

What was lost in this family’s departure was the conversation which never happened between this parishioner and other thoughtful adults in our congregation. Such intimacy would not only hold promise in evangelizing him, but would challenge our laypeople to rethink and restate their own faith assumptions.

Conclusion

The conversation about our experience of God has been stifled by at least these four factors: 1) the general breakdown of community, 2) the intellectual emphasis in the Reformed tradition, 3) secularization, and 4) privatization in American religion. In Presbyterian congregations talk of knowing God has drifted into talk of knowing about many things. The experiential character of faith has lost its voice. Additionally, the particular experience of conversion, an uneasy subject for Mainline Protestants because it is essentially spiritual encounter, is made more problematic because of its association with evangelism and revivalism as they have been practiced in the American context. We turn now to this factor as yet another reason why conversion is difficult to discuss in Presbyterian churches.

-

EVANGELISM AND REVIVALISM

Two false assumptions drive this kind of thinking: First, that evangelism is somehow not a part or a minor part of the Presbyterian experience, and, second, that conversion takes place only where evangelistic efforts are expended.

The First False Assumption: Evangelism is Not Presbyterian

Presbyterians are and always have been committed to evangelism–sharing the Gospel’s glad tidings with neighbors near and far. Despite this commitment, Presbyterians have long found that evangelism collides–or seems to collide–with other values which we hold dearly. The whole story of this uneasy regard for the task of evangelism is complex, dates back to the Reformation, and is beyond this chapter’s scope. It is, however, worth listing several factors that have troubled the relationship between Presbyterians and evangelism recently in the United States.

Evangelism and Theology. A basic problem, one which predates the Civil War in America, is the Presbyterian sensitivity to the competing needs both to evangelize and maintain allegiance to pivotal theological tenets such as predestination and limited atonement. The general situation in America with its expanse of wilderness and variety of immigrant settlers, demanded a simple gospel proclamation which quickly warmed hearts and led to conversion and church membership. This adaptation of mission for the American experience also led to conflict with Presbyterian immigrants who were committed to the Westminster Confessions’ nuanced theology and church discipline. This basic conflict is the essence of many now-famous Presbyterian upheavals including the Adopting Act (1729), the New Side–Old Side tensions, the Cumberland Presbyterian Church’s formation, the Plan of Union’s failure in 1838, and Charles Finney’s withdrawal from the Presbyterian Church.

Evangelism and Polity. Presbyterians also have long struggled with polity questions revolving around appropriate administration of evangelistic work. Para-church organizations such as evangelistic associations, mission societies, or traveling evangelists have generally lacked church discipline and accountability. This, in turn, has regularly alarmed orderly Presbyterians. Further, Presbyterians have long debated whether evangelism is germane to a congregation’s life or whether it was best administered by denominational boards. Thus, beginning in the 19th century, Presbyterian evangelism and mission have been hampered by controversy–theological and administrative.

Evangelism and Changes in the 20th Century. In 20th century America, a plethora of factors quietly worked to erode the evangelical character of Presbyterianism. For example, developments in European biblical theology have pressured Presbyterians to define themselves in the modernist-fundamentalist debate. Once again Presbyterians found themselves in a familiar dilemma–confronting intellectual reasons to examine the very theology which energized evangelism.

Further, the expansionist era for the United States came to a close in the 20th century together with the mentality that Americans needed to impose their culture–including Christianity–on other peoples. This played out in the growing recognition of the legitimacy and faithfulness of indigenous churches in emerging nations.

Further still, growing social problems during the 20th century tended to overshadow the sense of urgency to evangelize. The development of the science of sociology coupled with the insights of theologians like Reinhold Niebuhr and Walter Lingle increased Presbyterians’ awareness of the stake which all people have in social problems. In particular, the Great Depression with its vast unemployment brought social problems into high visibility. More recently, racial tensions and consciousness of race-related problems have grown in America. Observers of the language which Presbyterians have used to describe their outreach have noted a shift away from “evangelism” in favor of the word, “mission.”

Evangelism and Pluralism. Finally, the challenge of pluralism since the early 1960’s has presented perhaps the most daunting obstacle to evangelism. Ecumenism, which has led Presbyterians to acknowledge the priority of indigenous churches’ missions within their own cultures has been stretched to cover other faiths as well. Pluralism challenges Christian evangelism by raising the question whether truth is single or multiple. In view of increasing Christian respect for other world religions, the question follows whether we should evangelize pious non-Christian believers. This question is sharpened by recollection of abuses in our past evangelistic efforts.

Conclusion. Evangelism has long had a way of dwelling in the realm of controversy in Presbyterian circles. In turn, Presbyterians are rarely as zealous as other groups for evangelistic work. And while the long story of this uneasy relationship between Presbyterians and evangelism is usually unknown to laypeople, the sense that evangelism is problematic is not lost on them.

At the first session meeting which convened shortly after my installation as pastor of Central Church, each of the committee chairpersons introduced themselves. When we came to the Evangelism Committee, the chairperson said, “My name is Arlene. I’m the chairperson of the Evangelism Committee. And I don’t knock on doors.” That introduction probably represents more Presbyterian history than that elder may have realized.

The Second False Assumption: Conversion Only Occurs as a Result of Evangelism

This brings us to the second false assumption, namely that conversion is wholly tied to evangelistic efforts. The neglect of conversion is one unfortunate result of the Presbyterian tradition’s critique of evangelism in America. Beverly Gaventa asserts:

…Liberal Christians have avoided the task of understanding and reflecting upon conversion. Even the use of the term has been abdicated in some quarters. Surely this posture discards the baby along with bath water. If the category of conversion has been misused and misunderstood, then liberal Christians are obliged to develop a view of conversion rather than flee the task out of embarrassment.[xx]

In fact, such a “view of conversion” is a possibility in the Reformed Tradition. David Steinmetz has undertaken precisely this task by demonstrating that the American evangelical tradition has, by no means, embraced the entire scope of conversion. Steinmetz sums these up as follows:

These four themes from early Protestant thought–the denial of the possibility of preparation for the reception of grace, the insistence on the church as the context in which genuine repentance takes place, the description of conversion as a continuous and lifelong process, and the warning that there is no conversion which does not exact a price from the penitent–are certainly not the only themes which need to be considered by the church in the present as it ponders its own evangelistic mission. Indeed, they may even need to be corrected by insights derived from the Bible or other voices in the Christian tradition. But they are insights which cannot be lightly set aside.[xxi]

Unfortunately, neither these facets of conversion nor those emphasized in evangelical circles receive much attention in Presbyterian Churches. Our hesitations over the excesses of revivalism and our generally troubled relationship with evangelism, especially in this century, has effectively screened our appreciation of and conversation about conversion as well.

-

WHEN WE DON’T TALK ABOUT OUR ENCOUNTER WITH GOD

I’ve attempted here to demonstrate that a certain kind of conversation–witness to one’s personal encounter with God–is subtly devalued and therefore scarce in Presbyterian and liberal Protestant circles. For Mainline Christians in secular, individualist America, other forms of discourse–those undergirded by scientific validation or a part of a logical theological system–seem more promising in providing a useful world-view.

The eclipse of witness is important because it marks a quiet shift in the topic of our conversation away from the essence of Biblical faith, namely encounter with God. This is not to discount the value of theological reflection, ethical rigor, liturgy, and community. However, when these are abstracted from the ground of encounter; when they are second-hand and routine, then they become increasingly unlike what inspired them in the first place.

- Ellis Nelson has argued in How Faith Matures that religious faith faces multiple dilemmas when the founders’ experiences of God are not replicated in subsequent generations. For the Church, this means that faith will calcify and loose vitality if we don’t experience in our own lives encounters which resemble, say, Moses’ theophany, or the fishermen’s call or the upper room filling with the Holy Spirit. The founders’ original experiences of God serve to launch the tradition and provide models of how God works and how faithful people respond. But they cannot substitute for similar first hand experiences in each subsequent generation.

Faith matures, argues Nelson, through the transforming experience of God touching individuals in particular situations. Without this, rituals–once vital enactments of God’s presence–grow commonplace. So also do communities–once the gathering of those originally struck by a vision–grow rational and stable. Communication–once reflection on life-changing experience–slips into codification and definition.

Nelson moves on to assert that theophany, a literary form through which a community frames and remembers spiritual experience, is the vehicle through which someone’s personal experience of God can be communicated to the community. The importance of these cannot be overestimated. Nelson explains this as follows:

The narrative style, or story, of how a person experiences the Divine is extremely important for the spiritual health of a community of believers. What is required is for the community to re-present the religious experience to itself so that it may be able to receive further revelations from God and be open to change. In short, the community needs to discover how a personal experience with God can be translated into directives for the community. Theophanies are such accounts. They certify the guidance of God within the events of history, thus prolonging the presence of God and providing expectations of further visitations. Theophanies are the classical biblical way of affirming the necessity of religious experience to the corroding influences of institutionalization from secularizing the community of believers.[xxii]

For Presbyterians who have, for the reasons outlined above, lost their vocabulary of experience, Nelsons’ insight provides a rich clue to our spiritual condition. If indeed finding ways to talk with one another about our relationships with God is a vital source of congregational renewal and guidance, then Presbyterians, together with similar traditions within the Protestant family, are in a precarious place.

Earlier in this chapter, I quoted Coalter, Mulder, and Weeks who said, in effect, that Presbyterians, while still having experiences of faith, are inhibited from expressing them. As a result, they went on to say, Presbyterian evangelistic witness outside the church suffers through lack of practice.[xxiii] Nelson’s insights suggest that the situation is more dire than the loss of evangelistic mission. If, as he says, sharing of religious experience is necessary to stem the drift into self-serving institutionalism and dry formalism, then the hush of such talk among Presbyterians is certainly a factor in our current institutional dilemma.

- THE PROJECT

All that we’ve said so far suggests that if Presbyterians–I’m thinking of ordinary laypeople engaged in Christian community–could be coaxed into sharing with one another the personal stories of their own encounters with God, this exercise alone would be energizing and transforming. Such an effort would re-introduce the language of encounter into the fellowship. It is likely that several barriers to this kind of intimacy would emerge. Presbyterian congregants may be reluctant to commit themselves to participate because they would have little appreciation for such sharing. Understandably, they would probably feel shy or lack words which would convey their deepest convictions and inspirations. They may feel that such sharing is essentially un-Presbyterian. Strategies for overcoming these difficulties would have to be employed in order to make such conversation possible.

The project through which I propose to re-introduce the language of encounter into Presbyterian congregations will be detailed in the following chapters. It takes the shape of an adult class, employing Bible study and conversation. The spiritual experience under discussion is conversion. The course endeavors to bring participants’ existing attitudes toward and knowledge about conversion into dialogue with scriptural passages which narrate experiences commonly considered conversions. Thus, participants will develop their capacity to think and talk about conversion. Studying the Scriptures for insights about conversion will provide the foundation for students to speak personally about their own experiences of conversion. The project’s aim is to counter the loss of sharing about spiritual experience, specifically conversion, in Presbyterian churches.

Before we turn to the project, it is important to note that the topic of conversion in itself presents its own problems. One of these problems we’ve discussed here, namely, conversion’s association with the excesses of the revivalistic movements. There are other difficulties. Study of conversion is hampered by the fact that the term appears infrequently in the Bible. What’s more, religious conversions tend to be situation and individual specific. In other words, conversions are as diverse as the individuals who undergo them. So, even to state directly what the word conversion means opens up a variety of problems. Somehow these problems, specific to the topic, need to be held and pondered by the class.

The project I propose, then, is made complex by several factors. In response to the complexity of its subject, the class will feature different kinds of learning and teaching. The class not only aims to help students acquire information but also to process that information and to share personal stories with the others.

Despite these complexities, indeed because of them as we’ll see, the strategy outlined here is one whereby a congregation can use what God has already given to members for the transformation of the entire group.

To conversion and the project we now turn.

The entire document, “Conversion in Retrospect” may be downloaded by clicking Master Copy word pdf.

[i]. Milton J. Coalter, John M. Mulder, and Louis B. Weeks: The Re-Forming Tradition: Presbyterians and Mainstream Protestantism (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1992), p. 255.

[ii]. Sidney Ahlstrom: A Religious History of the American People (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1972), p. 159.

[iii]. Eugene H. Peterson: Five Smooth Stones for Pastoral Work (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1980), p. 13.

[iv]. M. Scott Peck: The Different Drum: Community-making and Peace (New York: Simon and Schuster Inc. 1987), p. 17ff.

[v]. Roberta Hestenes: Using the Bible in Groups (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983), p. 12ff.

[vi]. Wade Clark Roof and William McKinney: American Mainline Religion: Its Changing Shape and Future (New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press, 1987), p. 63-67.

[vii]. Noll, Mark A. Ed.: The Princeton Theology 1812-1921: Scripture, Science, and Theological Method from Archibald Alexander to Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1983), p. 18.

[viii]. Ahlstrom, History, p. 237.

[ix]. Edith Blumhofer: “Evangelism in Pre-Civil War American Presbyterianism,” (Unpublished paper given at the “Faithful Witness Conference” held at Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary on March 18-19, 1993), p. 16.

[x]. C. Ellis Nelson: How Faith Matures (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1989), p. 21.

[xi]. Ahlstrom, History, p. 1095.

[xii]. Ahlstrom, History, p. 966-1096.

[xiii]. Martin Marty: The Modern Schism: Three Paths to the Secular (New York: Harper and Row, 1969), p. 96ff.

[xiv]. Diogenes Allen: Christian Belief in a Postmodern World: The Full Wealth of Conviction (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster/John Knox Press 1989), p. 26.

[xv]. Ibid. p. 23.

[xvi]. Roof and McKinny, Mainline Religion, p. 56.

[xvii]. Loren B. Mead: The Once and Future Church: Reinventing the Congregation for a New Mission Frontier (The Alban Institute, Inc., 1991), p. 13ff.

[xviii]. Nelson, How Faith Matures, p. 37.

[xix]. Ibid. p. 38.

[xx]. Beverly Roberts Gaventa: From Darkness to Light: Aspects of Conversion in the New Testament (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986), p. 150.

[xxi]. David C. Steinmetz: “Reformation and Conversion” Theology Today, XXXV, (April 1978), p. 32.

[xxii]. Nelson, How Faith Matures, p. 77.

[xxiii]. Coalter, Mulder, and Weeks Re-Forming Tradition, p. 256.