Through Victims’ Eyes: James Baldwin’s Vision of Racial Justice

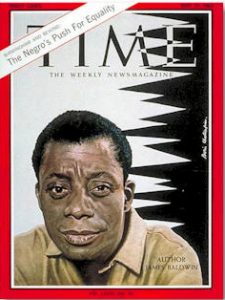

One of the Civil Rights Movement’s most penetrating voices was that of James Baldwin. He possessed extraordinary insight into the psychological dynamics of race and relationships. Baldwin’s prolific pen landed him on Time Magazine’s cover in 1963—a reminder of this nation’s smart journalism in those days, despite its entrenched racism. His first novel, Go Tell it On the Mountain, deals with Baldwin’ diseased family church, rather than with race. That church propelled Baldwin, still a teenager, out through its front doors into a grace-filled secular world where he lived the balance of his life. I will discuss that journey in an upcoming post. My work on Baldwin’ religious views took me to a 1962 essay printed in the “New Yorker,” titled “Letter from a Region in My Mind.”

Letter enabled me to confirm Baldwin’s mature attitude towards Christianity, which, in brief, is that it is tangled with conquest and White culture. The Christian God, Baldwin came to believe, is white. Go Tell is On the Mountain explores how the Baldwin family practiced this dysfunctional religion, which was the center of his Baldwin’ childhood, and eventually drove him away. More on that later.

Why Letter from a Region in My Mind?

I read and re-read the whole of “Letter from a Region in My Mind.” Almost 60 years old, the letter transcends its era, a time before MLK , identity politics, Barack Obama, and scientific discoveries pertaining to race. Though Baldwin wrote it early in the Civil Rights Era, Letter sparkles with its author’s intuition into America’s race dilemma. I’ve written this essay to re-present Baldwin’s more compelling ideas, which for me were at least as exhilarating as they must have been in 1962 for readers of the “New Yorker.” We ought not forget this stuff. It may yet mark the path forward for our own generation, that may still be as confused about race as our parents were in 1962.

Christianity

“Letter from a Region in My Mind” declares that there is but one exorcism of the race demon that haunts America’s spirit. And it’s not Christian faith, despite Martin Luther King’s ecumenical movement, which dominated Civil Rights through the 1960’s. King agitated for social change through Gandhi-like non-violence and the united moral voices of church leaders spanning the spectrum of Christian denominations.

One might expect James Baldwin to follow MLK’s pattern. Before his departure from Christianity, James Baldwin had become, in his early teens, a Holiness church preacher. But Baldwin later admitted that his three years in the pulpit, while popular with congregations, were little more than performance. Baldwin cleverly picked up the theatrics, the phraseology, and enough theology to dupe his parishioners into believing in his sanctification. Baldwin’s ploy was to out-preach his father. Succeeding at this, Baldwin moved on in his intellectual life and his writing. So, Church-going through his youth convinced Baldwin that Christian faith was fake, a conviction that solidified during those three years behind the pulpit. Baldwin Baldwin was looking for a non-Christian model of Black deliverance several years before Martin Luther King dominated headlines.

The Black God of the Nation of Islam

Baldwin liked the muscular Black Muslim approach to race much better. Through the middle of “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” Baldwin describes a dinner meeting with Nation of Islam’s leader, Elijah Muhammad. The dinner was cordial. Baldwin especially liked the NOI’s worship of a Black God that unambiguously sided with Blacks against other peoples. Quickly, however, Baldwin discerned that the Nation of Islam wasn’t going to banish America’s race demon. The NOI’s Black supremacy wasn’t the most off-putting factor for Baldwin. What Baldwin could not champion was the feature in Elijah Muhammad’s creed that declared Blacks to be entitled to their own homeland, territory carved out of some portion of the United States. Baldwin found this goal beyond realistic hope. The logistical impossibility of a Black homeland plus the logical dissonance of swapping White Supremacy for Black Supremacy doused any affection Baldwin might have had with Islam. As the meal with Elijah Muhammad ended, the assembled guests stood. As Baldwin bid goodbye to his host, he knew that any possibility that he would become a Muslim had already passed.

The Social Welfare State

Having banished religion as the organizing principle for Black empowerment, Baldwin explores another tactic for banishing the demon of race from the American soul. Simply stated, Whites give stuff to Blacks. The Social Service Agency pushes open its doors at 8:59 a.m. A line of African American women, some holding babies on their hips, has already formed. The social worker reads, rather than explains, the qualifications for receiving one or another government grant to a nervous lady who sits on the edge of the plastic chair. Usually, the interview ends fruitlessly and a poor woman moves on the Salvation Army Thrift shop and local churches for “assistance.” The next in line takes the chair and explains her need. The line stretches on forever. This is the picture of White America’s generosity-driven solution to its anti-blackness.

White Americans are convinced that the nation’s race demon will disappear if they can give enough stuff to Blacks. Stuff means the subsidy for the electric bill or payment for prescription drugs. It also means drawing from White America’s inexhaustible resources in order to provide for select Blacks token positions in schools, in businesses, and factories.

Baldwin scorns this scheme of covering the corpse of injustice with gifts drawn from White largess. This was an audacious stance for 1962, given the hard times Blacks endured and the fact that Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty was still two years away. Baldwin points out that the apparatus of White assistance for Blacks recalls a feature in chattel slavery, namely that the master assumes the stance of the all-giving lord. The Social Welfare state that grew out of the War on Poverty could never dismantle this mutual dependency in the White-Black relationship. Neither could it dissuade Whites of their grandiose delusion that they possessed the key to Black emancipation, and that all that was necessary was enough White compassion so that Blacks may become like Whites.

Baldwin is as blunt as he is prescient on this point. He doesn’t believe that all will be resolved should the Black Race come to live as does the White Race.

I cannot accept the proposition that the four-hundred-year travail of the American Negro should result merely in his attainment of the present level of the American civilization. I am far from convinced that being released from the African witch doctor was worthwhile if I am now—in order to support the moral contradictions and the spiritual aridity of my life—expected to become dependent on the American psychiatrist. It is a bargain I refuse.

With this, Baldwin, states: “The only thing white people have that black people need, or should want, is power…” For White America to surrender its power, or, stated in a more unsettling way, for Whites to surrender their entitlement and naïveté, is tantamount to their becoming Black. Baldwin’s exposure of the fairy tale—the narrative–that supports a White dream world, strikes me as the kind of thinking that only now is becoming current.

Life’s Tragic Core

At any rate, Baldwin proposes the dismantlement of White privilege and the narrative system that legitimizes it. To do this is to enter into a mature state of being that acknowledges life’s tragic core. Baldwin sees the 400 years of slavery and the additional century of slavery’s after life, namely Jim Crow and discrimination, as fostering in the African American community an identity engulfed by tragedy. Paralleling Black tragedy is a counterbalancing White idealism, especially in the post-WWII period. Baldwin sketches in Letter the interdependence of tragedy and privilege. Blacks suffer, Whites are pampered and naïve. Women today who are making public their sexual victimization by powerful men are challenging the same interaction between privilege and subjugation that Baldwin was seeing in 1962.

Baldwin ponders suffering. Suffering is indispensable for growing up. The suffering of the American Black, while deplorable, generates a measure of insight and beauty. Baldwin’s first inkling of struggle’s beauty washed over him as he walked the stairs in a tenement building, looking at urine and wine stains on the walls. These testified to the enormity somebody’s exertion and bereavement.

Struggle yields wisdom. Black men and women’s suffering at the hands of Whites has been so enduring and the fortress of White Supremacy has been so unassailable that Blacks have found the path of bitterness too burdensome to walk. It is a hard-won wisdom that realizes that I must lay down the weight of resentment. This coming to terms with one’s bitterness is not forgiveness, nor reconciliation. It’s self-preservation. Wisdom is for Baldwin is surrender to a hard truth. If you’re Black, life in this country is just going to be like this.

Through the Eyes of the Victim

Baldwin doesn’t stop with the sweet side of suffering. Diving deeper into the cold waters of Black experience, he detects the outline of another mammoth treasure. He will explore this find more carefully elsewhere. But what he sees in Letter is this: no one knows someone like his victim.

The midnight lynching party, cloaked so not to tarnish its members’ daytime image, tearing the teenage boy from his mother’s arms, stripping him, castrating him, and hanging him, is probably better understood by the youth’s family than anyone else. The nightrider’s wife puts on her bed clothes and pushes away the thought of what her husband might be doing out in the middle of the night. The victim, on the other hand, knows, in an almost biblical way of knowing, the extent of the mob’s cruelty, cowardice, and the way its common decency flutters away like feathers on a puff of air when its members are provoked. Says Baldwin,

Negroes know far more..about white Americans what parents—or, anyway, mothers—know about their children, and that they very often regard white Americans that way. And perhaps this attitude, held in spite of what they know and have endured, helps to explain why Negroes, on the whole, and until lately, have allowed themselves to feel so little hatred. The tendency has really been, insofar as this was possible, to dismiss white people as the slightly mad victims of their own brainwashing.

The German philosopher, Friedrich Hegel, famously observed that masters and slaves owe much of their identities to one another. The master is pathetically beholden to the underling who is indispensable if the master is to be a master. The slave is beholden in similar fashion to the master. Whatever the slave possesses, enjoys, wears comes from the Master’s hand. The master assigns to the slave’s his or her purpose. The Master is as tightly fastened to this arrangement, as is his slave. One thinks of Gilligan and the Skipper. We have little idea what stirs in the Skipper as a full-orbed human being. Who is he, what he loves and hates are mysteries. We don’t know this man without Gilligan. In same fashion, Gilligan takes his cue and enacts his silliness in the context of the Skipper’s projects.

Baldwin has painted a picture of White and Black in the thrall of one another. Each is forced into a grotesque contortion because they are unevenly joined. True humanity is a possibility for both in the relationship only when the master-slave connection is overthrown. Nothing will remedy this mutual bondage save the power that makes right every human relationship. That power is love. By love, Baldwin means that Whites must grow up and stop living in their fairy tale world, stop denying life’s reality, stop clinging to entitlement, and to regard their Black neighbors as a co-equal human beings.

Both races must recognize, additionally, that the opportunity to rectify their centuries-long struggle will not wait forever for their response:

Everything now, we must assume, is in our hands; we have no right to assume otherwise. If we—and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others—do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world.

The Impossible Task

In Letter’s final sentences, Baldwin admits that his proposal is “impossible.” “Impossible” doesn’t mean despair, because Baldwin concludes his essay with a splash of whimsical optimism. The history of Black endurance is nothing less, he observes, than the achievement of the impossible. Human history is the history of the repeated achievement of the impossible.

Baldwin returns to beauty. He sees in Black struggle an inescapable splendor. He detects beauty in the Black-White bond through America’s history. It’s like the beauty of a long, bad marriage. Husband and wife have reached their eighth shabby decade after years of self-absorption, brief affairs, and neglect of one another. But mediocrity isn’t their entire story. The couple has children. They’ve built a home. They’ve been patriots and good neighbors. They may have endured a shoddy life together, but it is a life that was better for both than the lives they would have lived alone. Something yet shines in their bond.

Baldwin ends his essay with the tender acknowledgment of a splendor that shines in the terrible history of Black and White in America. To lose this beauty, should Americans in their intransigence allow the history’s judgment to fall upon their wickedness, would be unthinkable. Baldwin’s love of country and his people is unmistakable in this crowning sentence:

If we—and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others—do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world.