THE HALF HAS NEVER BEEN TOLD: Summary and Notes

What Reading this Book has Meant for Me

I’ve just finished Ed Baptist’s remarkable book on slavery, The Half Has Never Been Told. This book joins Eric Foner’s and Henry Louis Gate’s books on Reconstruction, (click here and here), Isabel Wilkerson’s book on the Great Migration, Ibram Kendi’s history on racist ideas, and Howard Zinn’s rewrite of American history as the most compelling voices, which bear the sobering message that we must consider anew who we are and what we have done as a people.

Slavery was a big deal. America took its place among economic powerhouses like Britain and France because it was able to flood world markets with cheap cotton–all planted and picked by enslaved labor. We didn’t hear this in school. Neither did our kids. This is because the American South, with tacit permission from the rest of the country, put forth a monumental effort to cover over slavery’s enormity and atrocities.

Ed Baptist is aiming to correct this record. He’s making the economic argument that American slavery was not only big, but that it was essentially capitalist. In other words, it carried the same DNA that made the Industrial Revolution great and brought the Internet to life. Slavery was not a relic of some other culture like plowing with Water Buffalo. It was American, capitalist, efficiency-driven, and adaptive.

Slave holders thought of their enslaved workers more as financial assets than as human beings. Enslavers might sell a few enslaved people to finance a college education or a trip to Europe. Some enslaved people had mortgages taken out on them. Their work was measured. Some of them came with guarantees.

I was surprised how much I learned from this book. Slave state politicians, for example, protected and expanded their slave-based economies with brilliant and aggressive tactics. Legislators from the South dominated American politics from the constitutional era until the Civil War. The cotton economy suffered very few if any setbacks in Washington. Accordingly, the Three-fifths Compromise, establishment of the Senate, postponement of the ban on trans-Atlantic slave transport, the Missouri Compromise, fugitive slave laws, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act, are all political victories pushed by the slavery caucus.

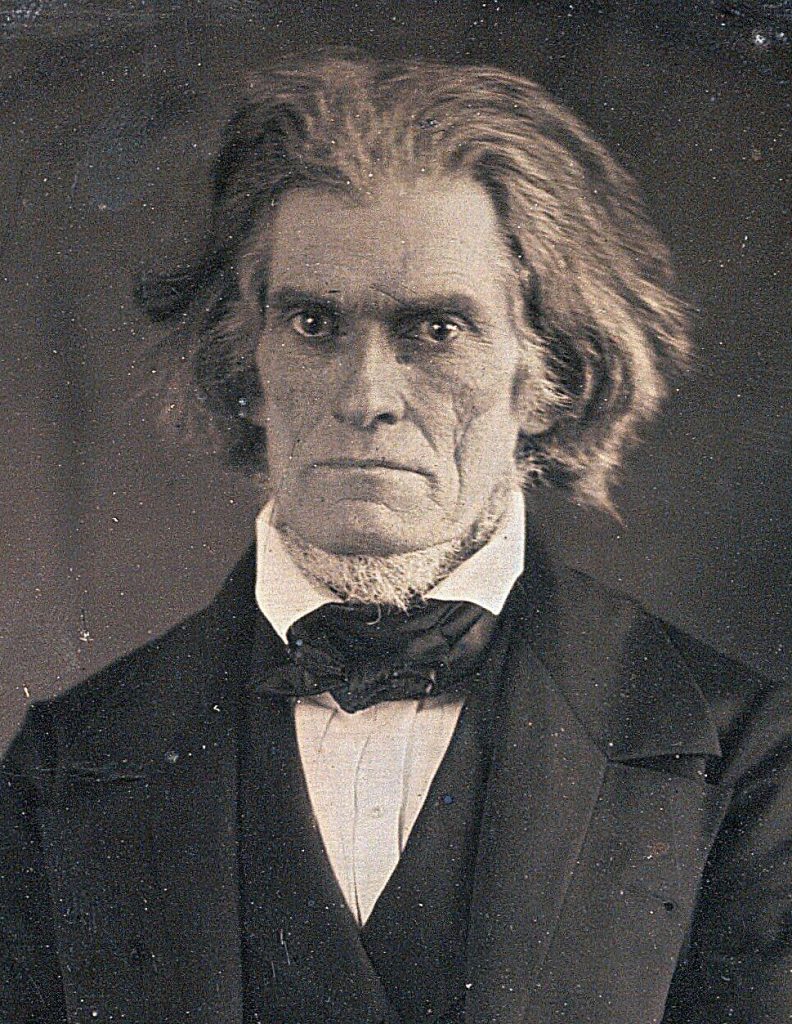

Wiley statesman like John C. Calhoun and Stephen Douglas hatched brilliant strategies that out-maneuvered Free State politicians. Throughout the 19th century, the wholesale theft of human lives, the separation of children from parents, the use of torture to extract unrelenting toil from human bodies met very little moral hesitation.

Baptist argues that without Lincoln and a bloody civil war, slavery would have engulfed North America and lasted for decades beyond the 1860’s.

Slavery, Baptist’s book emphasizes, thrived on expansion. It withered wherever it settled down as a permanent part of life. For example, the old East Coast tobacco farms grew unprofitable with time. But as tobacco returns shrank, cotton was entering its boom period. Just because enslaved persons harvested a crop was no guarantee that that product would remain profitable. American slave holders were adept at the classic capitalistic skill of moving beyond the unprofitable confines of one business for greater profit in another. They did this by changing crops, transferring captives, reselling slaves, and reviving forced labor for even greater profit elsewhere.

Slave-harvested crops used up the land. Planting one crop season after season depleted the soil. Planters were perpetually yearning to expand onto new land further and further to the west during the King Cotton era.

Cotton production benefited from several seemingly limitless resources, which converged to create a super-powered industry and export. First, cotton enjoyed unlimited demand as the prime raw material needed to feed Europe’s steam powered spinning and weaving machines. Unlimited credit also fueled cotton’s expansion. So did huge expanses of free land, perfectly suited for cotton growth, which had been stolen from Native Americans or annexed from Spain, Britain and France. Capping off all of these benefits was limitless free labor, which allowed planters to capitalize on the amazing convergence of favorable factors to create a money-making machine to which the entire nation became addicted.

Tragically, the captive free labor was a population of human beings. Baptist brings to light the hopelessness of the captives themselves who had their own range of feelings and aspirations. Where labor camps were plentiful there were also lots of guns and volunteers available to suppress any slave uprising. Planters counted on US Army troops to ride to their rescue when the large population of enslaved labor grew restive or when frustrations boiled over.

The Abolitionists in the North had influence that exceeded their numbers, but their moral suasion never tipped the opinion scales against King Cotton.

Though hopelessness engulfed slaves’ lives, their humanity, found in their writings dance, spirituality, and music, never flickered out. Out of the cauldron of toil, torture, and displacement arose a musical tradition that came to be known as uniquely American. These musical forms include gospel, soul, jazz, ragtime, blues, and bluegrass and were first heard in slave cabins, fields, and later in slums and night clubs. For example, bluegrass, usually credited to Bill Monroe and Earl Scruggs and played by all-White bands, is anchored in the driving energy of the five string banjo, an instrument of African origin. It often surprises people to learn that most of what can be called original American music is usually Black music, which mainstream culture has ripped without credit from the fields and ghettos and presented as a national achievement.

A final thought kept running through my mind as I worked through Baptist’s book. The effort to hide what happened in those labor camps was monumental. Most of the Southern literary output in the 19th century was laced with propaganda designed to romanticize Southern culture and the practice of slavery. I’ve been interested in the Plantation Novel genre of fiction. This literature might be chalked up as nostalgic romance tales. But these books were also one of ways that the South employed to change the story about slavery.

The Half Has Never Been Told counters the massive propaganda campaign, well under way by the mid 1800’s, which romanticized slavery and the society that profited from it. Baptist’s well-researched book exposes Lost Cause and Plantation Novel propaganda, not as a shading of the truth, but as a black lie.

Caroline Lee Hentz’s 1854 novel, The Planter’s Northern Bride is typical of the effort to sanitize slavery. Hentz was a New England-born school head mistress writing just before the Civil War. Her novel, a love story, bristles with passages that trot out the pro-slavery arguments that, until recently, dominated America’s collective memory of the nineteenth century South.

This passage, the musings of a fictional enslaver reflecting on his way of life, is typical of the way that the Old South has come to be remembered.

What follows are short summaries of each of Baptist’s chapters. These summaries and the infographics woven into them will help readers to benefit from Baptist’s key arguments, even if they don’t have time tackle a 400+ page book.

Introduction

The Half Has Never Been Told’s introduction is organized around a WPA interview of a former slave in 1938 in Danville, Virginia. Some 70 years before, Danville had been a hub of Civil War activity. Following the war, the interviewee, Lorenzo Ivy, trained to be a school teacher.

During the years that stretched between the Civil War and the interview, Americans had been lulled into a sanitized recollection of slavery and race in their society. What began with emancipation was a promise of freedom and dignity for newly freed African captives. But the collapse of Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and the rise of racism nationwide twisted the promise into a betrayal. Further, a consensus emerged among historians and scientists that Africans were somehow destined to inferiority, that slavery was not driven by lust for profit, and that captivity was the natural habitation for Africans.

Quietly, Americans disassociated slavery with the accelerating prosperity that they were enjoying and crediting themselves with creating. Myths about slavery persisted even after the Civil Rights movement’s efforts toward desegregation. One such myth was that slavery was not essentially American, nor part of capitalism’s DNA. It is as if the country was telling itself, “This wasn’t us. This wasn’t how we developed and generated our wealth.”

Also lost in the Great Sanitizing is the remembrance of just how cruel slavery was. If slavery simply denied workers a paycheck and civil liberties then the Emancipation Proclamation and the granting of citizenship should have rectified any wrongs done. If, on the other hand, slavery was unthinkably cruel, kills people, tears apart families, denigrates people’s humanity, and rips people from their home and heritage, then making right those wrongs is a much deeper problem. The book’s title, words attributed to Lorenzo Ivy, sums up the need to tell the whole truth about slavery by recovering the “half that hasn’t been told.” That untold half isn’t that slavery was an anomaly in Southern life and was on the brink of collapse anyway. What needs to be told is that it metastasized through the 19th century into an economic and social colossus.

Baptist brings the Introduction to a close by recalling Ralph Ellison’s metaphor that the whole of American life is like a drama enacted upon the body of a Negro giant tied down like Gulliver. This image gives structure to the book’s chapter divisions, with each chapter being named after a body part (eyes, feet, etc.) of the giant. Finally, Baptist repeatedly emphasizes Slavery’s expansionary nature as its most pernicious quality. The planters wanted to make all Western lands slave economies. It is this lust for growth that appears to be slavery’s most evil and self-destructive aspect.

Chapter One: Feet

The first chapter, titled, “Feet” shows how slavery allowed the newly established United States solve several of its initial challenges. The Atlantic slave trade deposited the great majority of captive Africans at ports in the Caribbean and Brazil. Nevertheless, the smaller numbers of captives, totaling about 20% of the population, brought to what became the United States played a decisive role in enabling the country prosper economically and remain united politically. The simple fact that slaves were a moveable form of capital allowed their owners to transport them to Western territories where they could labor in new crops, notably cotton.

From the beginning of the republic, the Founders were ambivalent about slavery. Thomas Jefferson, himself a slave owner, believed that slavery made White men into despots and contradicted the emerging national vision of freedom as a God-given right. In turn, Jefferson and others

argued that Western lands be slavery-free. The republic’s early problems, especially the weak central government under the Articles of Confederation confronted policy-makers with a host of problems. The new United States was beset by debt, disputed land claims, and threats that Western territories would realign with Britain were among the woes of the new nation.

Slavery might have died out if it remained tied to the failing tobacco production around the Chesapeake Bay. The combination of expanding slavery and expanding land proved to be a powerful force in uniting diverse interests and fueling the economies in both the North and South. Policy-makers found it much easier to discard their uneasiness over enslaving people in order to appease Southern planters, gain national control over Western territories, and generate exports that stimulated the economies of all regions.

The Three-fifths Compromise, especially when combined with the Great Compromise (establishing the Senate), and the electoral college granted extraordinary power to southern states with large slave populations.

At the time of the Constitution, Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia had western lands that were to become states in their own right. For Kentucky, general agriculture, and for Alabama and Mississippi, cotton crops were greatly energized by the use of enslaved labor. So as the profitability of crops on the Eastern seaboard declined, slaves were sold and marched West. These treks called “coffles” consisted of captive men being manacled together and forced to walk hundreds of miles.

A final factor in the expansion of slavery was an idea which circulated among Whites held that too great a concentration of Blacks, captive or free was a threat and dispersing African descent people throughout the country would keep their numbers from becoming too numerous.

Chapter Two: Head

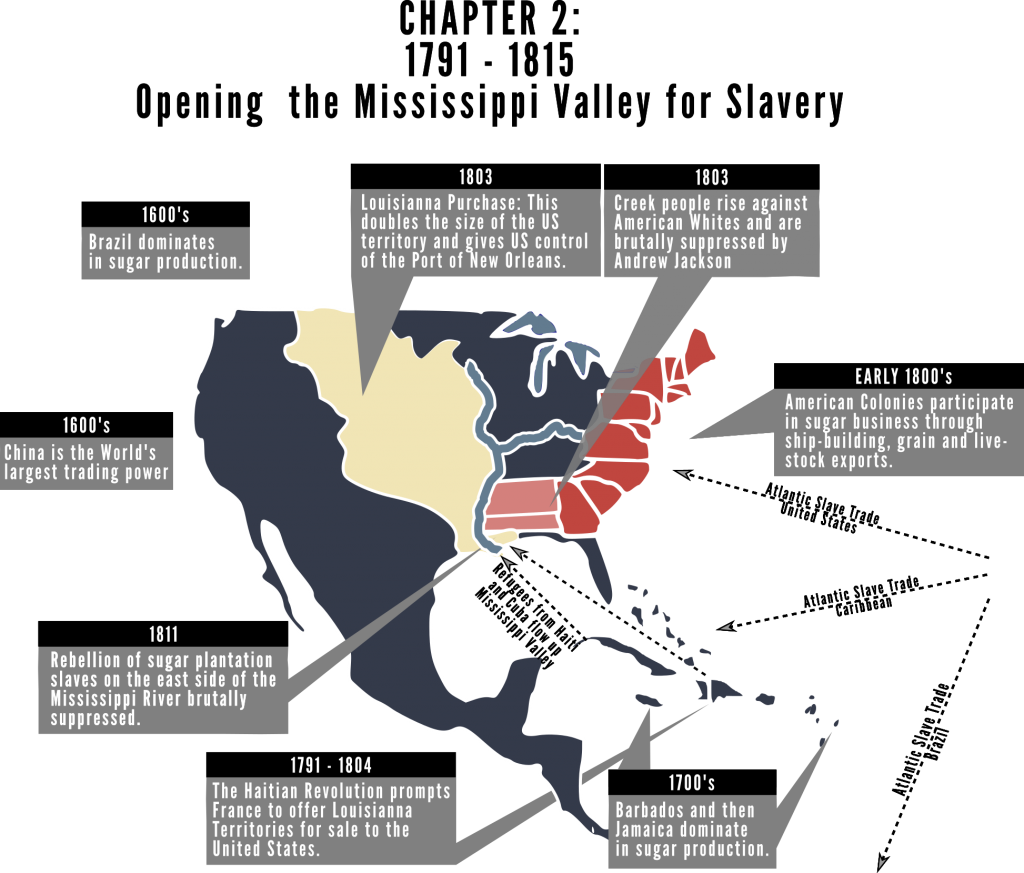

This chapter tells how the Mississippi Valley opened to the unlimited expansion of slavery.

Four conflicts created conditions for a modernized slavery to take root in the sugarcane plantations of the lower Mississippi Valley.

First, the transatlantic slave trade moved, with great cruelty, captives into Brazil, the Caribbean, and the U.S.

Second, the Haitian slave rebellion and revolution caused a beleaguered Napoleon to withdraw from French claims in the North American heartland and to sell the territory to the United States.

Third, the 1811 slave rebellion in the lower Mississippi sugar plantations prompted the twin actions of U.S. government troop intervention and the stiffening of control of slaves by their owners.

Fourth, the defeat the British and Creek peoples during the War of 1812 and under Andrew Jackson, opened New Orleans, Georgia and Alabama for American control and the expanse of slavery. Following these interlocking events, America enjoyed an open door for the expansion of slavery into the foreseeable future.

Chapter Three: The Right Hand

The third chapter looks at slavery’s business aspects, focusing mostly on the boom years between 1815 and 1819 in New Orleans. The chapter revolves around three focuses: First, Mississippi Valley cotton’s role in the Industrial Revolution; second, the role that finance and banking played as an accelerant to slavery’s growth; and finally, the degrading effect that re-auctioning captives had for individuals who had probably already been slaves for their entire lives.

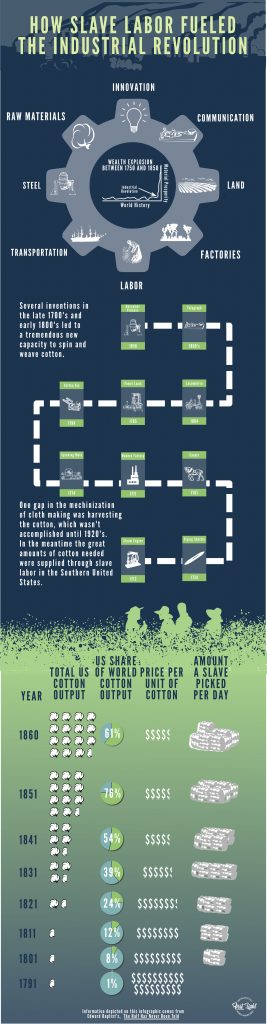

The American South’s cotton production grew and created colossal wealth because it was embedded in the textile-centered Industrial Revolution.

Several spinning and weaving innovations in England made it the world’s

leader in textile output. Additionally, England’s newly acquired ability to turn heat into movement through steam engines gave her a worldwide lead in textile production and shipping with steamships, steamboats, and locomotives. Britain’s spinning and weaving factories had an insatiable demand for that most basic raw material in the textile industry: cotton.

Cotton’s production sequence begins with vast acreage in near-tropical climates. What follows is planting, harvesting, shipping, processing, and export. In 1815 the weak link in the production of cloth was the planting and harvesting, which wasn’t mechanized until the late 1920’s. The warm climate and vast unclaimed land needed to grow the crop was newly available in American South. Not only plantation owners, but a host of American business-people, politicians, and consumers created a vast system that forced enslaved people to a life of unremitting toil in order to keep pace. The whole process generated vast wealth for a few and a measurable bump in life quality worldwide.

Between 1815 and 1819 New Orleans, strategically situated on salt water at the Mississippi’s delta, grew into America’s fourth largest city. A necessary component of New Orleans’s vibrancy was its need for financial services. Newcomers flooded the city. Speculators and settlers needed credit to purchase land and slaves. Cotton bales ready for shipping accumulated on the Mississippi’s levees.

The Bank of the United States provided much of the credit planters needed to purchase land. And private individuals also extended credit, bought cotton futures, and provided a host of financial services. Baptist gives a vivid description of entrepreneurs wheeling and dealing and lubricating the entire economy with their deal-making, while gathered in the French Quarter’s Mospero’s Coffee House,

The final pages in Baptist’s third chapter reflect on the dehumanizing impact on captive people who were re-auctioned in New Orleans after being marched or shipped over water for new work on cotton plantations. Much like the suffering of their forebears who were ripped from their homelands and families in Africa, America’s internal slave trade and the “new slavery” in cotton fields visited upon the grandchildren of the first slaves a fresh dose of dehumanization. Young men were especially desirable as field hands and sold at premium prices. Enslavers weren’t interested in families and especially not in children. So prime field hands had usually been forcibly separated from wives and children before being force-marched to the cotton fields. Several other dimensions of cruelty emerge as people are displayed and bid for on New Orleans’s slave markets.

Chapter Four: The Left Hand

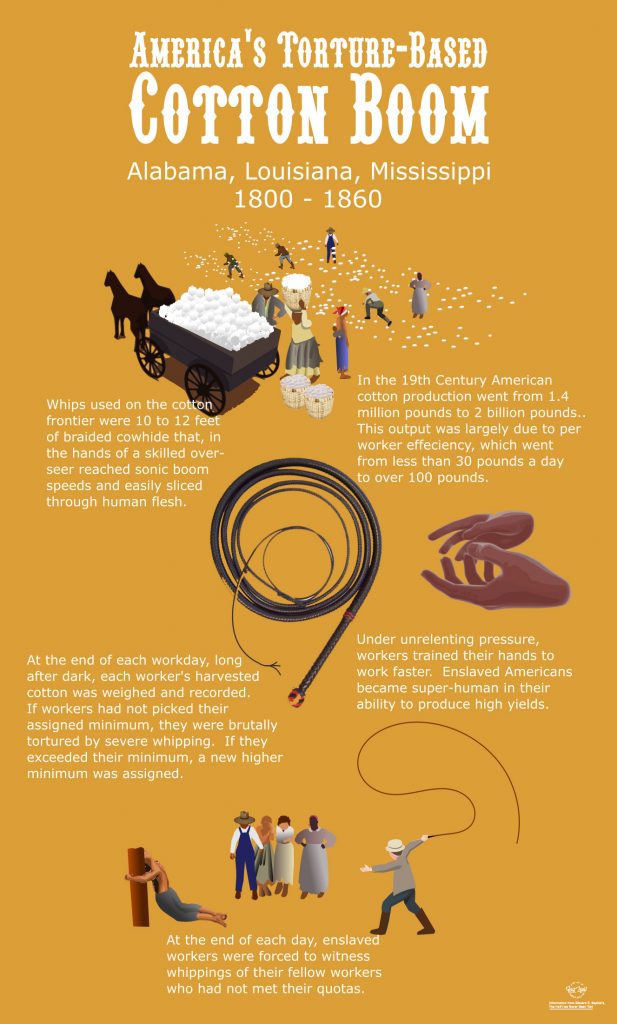

Chapter Four describes the “pushing system,” which was the systematic use of torture to increase cotton production mostly in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana between 1800 and 1860. During this time, american cotton production rose from 1.4 million pounds to 2 billion pounds. Each enslaved worker’s average productivity swelled by 400% to keep up with similar increases in Britain’s factory output. Also, as the “whipping machine” reached its zenith of cruelty and effeciency, cotton’s price in 1860 was 1/4 of its 1800 amount.

Not surprisingly, the toll that this torture-based economy took from the enslaved workers was enormous. Blacks in labor camps across the South suffered from high infant mortality, malaria and other diseases, and other forms of violence, notably hangings and other punishments.

Driven by the whip, enslaved cotton pickers managed to increase their work output by 300% between 1800 and 1860. Picking cotton at greater and greater speeds was achieved by neuro-muscular development in hands and brains. Blacks would say that their picking ability resulted from being educated by the whip.

Chapter 5: Tongues

The fifth chapter is about how hard-pressed field workers responded to their condition, which grew especially harsh after 1820. These were the years when cotton boom slavery was gathering strength. This was a time when America was expanding into Western territories, which held the promise to bring more cheap land under cotton cultivation.

Many Americans, especially those living in the north, wanted to limit slavery’s spread and see it die naturally. Political agreements, such as the Missouri Compromise, established the practice of admitting new states in tandem, one slave and one free. This arrangement didn’t squeeze slavery into manageability, but instead wove it into the fabric of the growing nation.

When negotiated agreements permitted half of America’s new states to enter the union as slave states those agreements bestowed legitimacy on the practice. As policy-makers struck agreements they wove slavery more and more into the fabric of the nation. In turn, the moral argument against the practice fizzled. From the enslaved Black’s point of view, the prospect of being set free disappeared over the horizon.

Back in the fields and under the whip, enslaved Blacks would often carry on in a listless way. Many, however, expressed their humanity by bestowing tiny favors on one another in the few hours available at night in their cabins. From this slave cabin culture emerged some of the most distinct forms of Black culture including the Black English Dialect, free-form dancing, and several new musical forms. The banjo, as it turns out, is not a uniquely American instrument, but an import from Africa, which has gone on to become a beloved American tradition. Much the same can be said of the Blues, Jazz, Soul, Rap, Ragtime, and other distinctly African American innovations.

Chapter 6: Breath

As slavery grew in scope and depravity it effectively reduced its victims to the status of material possessions. One rich data trove, which quantifies this dehumanization is the Notarial Archives in New Orleans. Here are housed the extensive slave sale transaction records required by old Napoleonic Laws. These reveal ups and downs of slave prices, which, like commodities, tracked with other economic variables. Slave prices tended to rise and fall with cotton’s sale prices.

Another sign of commodification was certificates of good behavior and skills that were frequently attached to enslaved persons moving from the old Eastern slavery to the new slavery in cotton country. Additionally, slave brokers came to be a lucrative profession in its own right and in some declining tobacco areas slave sales outstripped crops as the main economic activity. Even on a personal level, families would sell slaves in order to generate cash for retirement and other life cycle purchases. Captives themselves described slavery’s dehumanizing character as stealing. Their lives, families, and dignity had been stolen.

As slavery’s roots dug deeper into the country’s soul, the prospect that enslaved people would be freed grew remote. One small chorus of voices calling for emancipation and justice were those of the abolitionists. Both Black and White, Christian and secular, these social progressives pleaded for an end to chattel slavery. Several abolitionists are named in Half Has Never Been Told. The most striking and controversial of those named in Baptist’s book was David Walker, who wrote An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World. This book, which called for a violent slave uprising, activated the paranoia of enslavers across the South. The writings and speeches of the abolitionists had an impact far greater than their numbers. Planters reacted to the abolitionist movement with a counter-movement of writing and by shoring up defenses against a violent revolt.

The Second Great Awakening gave birth to an Evangelical Protestantism that “grew up in tandem” with the second slavery. The 19th century’s emotional revivals appealed to Whites and Blacks alike who were caught up in the romanticism of the time and welcomed fiery preaching and bizarre manifestations of Holy Spirit indwelling. The revival’s emotional atmosphere and ecstatic behavior had a deep West African pedigree and White preachers were happy to ride along on its power. Not surprisingly, there was enough biblical Christianity in the revivals to put the basic principles of human dignity, liberation, and justice in front of all participants. And sparked the launch in the middle of the 19th century several social movements that combated women’s subjugation and alcohol abuse. This new moral vision in turn raised afresh the question of slavery’s morality. Unfortunately, what began as spiritual common ground between the races, ended as a new American religious apartheid. The enslaving regions, anxious about any incentive for their enslaved populations to rebel, decided that the justice and kingdom elements of Christianity needed to be suppressed, at least for Black Christians. The slavery interests enacted a series of comically unjust laws forbidding Black religious gatherings, de-emphasizing the use of “brother” and “sister,” which were social levelers in congregations, and distributing censored slave Bibles, which suppressed aspects of Christian faith that strayed too far from the individualistic sin-redemption duality.

Chapter Seven: Seed

The Half Has Never Been Told’s seventh chapter, “Seed,” brings into focus two large systems that swirled out of the Southwest’s slave economy. First, pugnacious White masculinity emerged from the cotton frontier. White men of the South have long been sensitive to slights and put-downs. Even today, men in the former slave states exhibit heightened sensitivity to their social position and the respect accorded to them. Second, the Southwest’s slave-based business climate, propelled by the energy of free labor, free money, and free land blew westward with tornado-like energy, sucking in more and more people and resources.

Baptist begins the chapter with Robert Potter’s life story. A scrappy non-aristocratic North Carolinian, Potter made his way from this home state in the Southeast to New Orleans. Over his lifespan, he left a trail of exploits including arrests, honor-violence, election to political office, and founding of a “political university” designed to help non-elite men rise above dominance by the rich.

Potter illustrates the masculinity that the slave frontier fostered. Through his life, Potter struggled to steer between the planters and financiers above his social position and the enslaved Blacks beneath him. Potter needed to be vigilant to prevent being bullied by elites who seemingly might reduce him to the plight of the enslaved who were powerless to fend off being bullied and humiliated. Potter’s story makes clear why murder and violence in the South were sharply higher than anywhere else in the Western world.

Another feature of frontier masculinity was the planters’ shameless use of enslaved women as sexual partners. As with the commodification of men, women also were marketed and purchased on the basis of their desirability as sex partners. The collateral damage of this slack moral climate took the form of mulatto “children of the plantation” and humiliated wives. So socially sanctioned rape joined honor-violence and greed as part of the degraded moral climate of frontier life in the cotton states.

With Robert Potter’s serving as an example, Baptist introduces Andrew Jackson as an example of southern masculinity and frontier values. Andrew Jackson was of modest birth but he was relentlessly combative because of this he was admired by the mass of non-elite constituents, who celebrated his inauguration with a brawling bash that upended furniture and laid waste to parts of the White House.

One of Jackson’s exploits illustrates the bravado he embodied. He ended the charter of the United States Bank, headed by blue-blood director Nicholas Biddle. Biddle’s bank did not cease operations immediately. But Jackson’s actions created a credit void that a group of start-up banks filled. The most notable of these was the CAPL or Consolidated Association of Planters of Louisiana. This bank was the work of planters themselves who put their heads together to invent credit generators that the staid USB wouldn’t provide.

Local and state banks invented slick banking tools to steer money into the cotton economy. Mortgages, for example, were taken out on slaves and that money was used to buy land and pay other debts. Cotton buying countries in Europe invested in America’s cotton business, making cash available to planters to buy even more land and slaves. Planter debt was securitized by being pooled and divvied up into salable chunks. Slave buying, selling, and transporting became a business in its own right, replacing planters at the slave auctions with professional traders.

Adding new money to the existing resources of abundant land and labor stirred up a roaring economic engine that made cotton America’s largest export and the value of captive persons equal to 20% of America’s wealth.

Chapter Eight: Blood

Edward Baptist’s Eighth Chapter, “Blood 1836-1844,” in The Half Has Never Been Told revolves around the twin financial crashes in 1837 and 1839. The early 1830’s saw great expansion in the cotton economy. By 1836 the United States government had dumped 400 million dollars, a total that was approximately one third of the US economy, into cotton enterprises. A quarter of a million slaves had been moved to the cotton Southwest and 48 million acres of public lands were sold. Cotton output rocketed from 732,000 bales in 1830 to 1.5 million in 1936.

During the 1830’s, Texas, originally belonging to Mexico, became a big factor in the United States economy. Andrew Jackson triggered the sequence of events that led to annexation and statehood for the Lone Star state. But before Texas was part of the United States it proved very useful to cotton interests as an independent territory or country. It was possible, for example for slaves to be delivered to Texas, which was exempt from the ban on the international slave trade. Southern planters poured into Texas in search of new lands and shelter from US laws. The push into Texas rankled Mexico, which under Santa Anna conducted his famous siege and slaughter at the Alamo. Santa Anna was later defeated at the battle of San Jacinto, effectively freeing Texas for US annexation and an unhindered expansion of slavery. Concurrent with the drama unfolding in Texas a full scale financial crash was developing in the United States.

Once Texas was declared independent of Mexico a financial bubble began to build. In 1836 Andrew Jackson issued his specie circular order that mandated public lands purchases be made in gold or silver. This brought to a virtual halt government land sales and triggered a financial liquidity crisis that coursed through the entire US economy, especially in the high-leveraged South. The financial crises which continued into the 1840’s had an impact on not only business, but also social mores in the South. Captive people were sold to raise cash for planters awash in debt. In many instances, Southern debtors simply declined to pay creditors, or worse, they slipped away to Texas. European financiers were furious with deadbeat southern borrowers, a factor that marred the South’s reputation as a reliable business culture.

Edward Baptist here offers several insights into divergent masculine ideals, one for White men, a second for Blacks. White men devised schemes to evade debt or start afresh. Black men continued to be reshuffled and separated from family. Rebellion or retaliation was fundamentally out of reach for enslaved men, who needed to find dignified ways to endure their captivity. One way was to cultivate what Baptist calls ‘ordinary virtues.” These included self-forgeting care for those around and willingness to improvise with love relationships when families were repeatedly broken apart. Specifically, this meant rearing someone else’s kids and “marrying” technically married partners. The act of loving and rearing children with available partners in slave conditions can be seen as profoundly hopeful endeavors.

The chapter ends with a brief survey of president John Tyler’s Secretary of State, John C. Calhoun’s maneuvers to extend slavery and insure its unlimited survival. Most notably, Calhoun knew how to leverage popular American anti-British sentiment to secure a voting block which allowed not only acquisition of Texas but other territories in the Pacific Northwest.

Chapter 8: Backs

By 1850, slavery had intertwined itself in the economic and political life of an expanding United States. The twin crashes of 1837 and 1839 left the Southern planter economy in disarray and revealed New England industries to be rapidly catching up with the previously prosperous South.

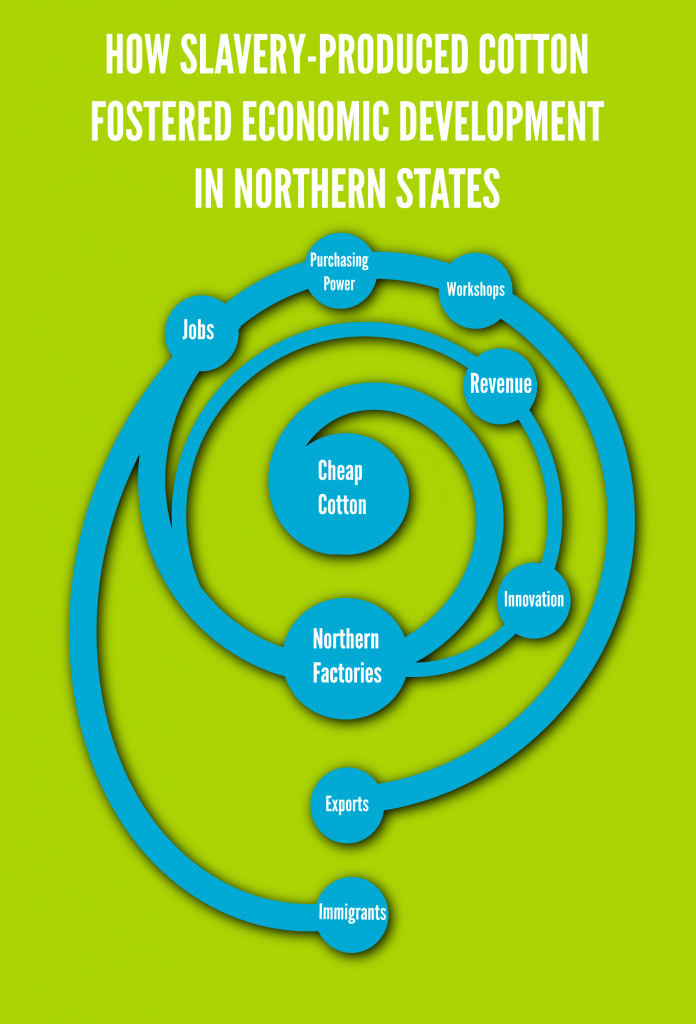

Britain was a quarter century ahead of the American Northeast in industrialization. Nevertheless, investment cash and the example of British innovation enabled Yankee factory owners to build and compete with textile mills across the Atlantic. Cheap slave-produced cotton fostered a virtuous cycle of investment capital, factory building, worker employment, consumer demand for goods, a secondary growth of workshops and businesses, and an influx of immigrants providing cheap factory labor enabled the Northern states to catch-up economically speaking with its agricultural southern states. Northerners also incorporated innovations in their factories, notably the use of steam power to drive machinery and a knack for tweaking British designed machinery for even greater output.

While Northern hubris drove many to denigrate the South, economically disabled in the late 1830’s and 40’s, cotton still drove about half of the US economy in 1836. Northern States’ population was also swelling from immigration bringing their representation in Congress to 2/3 of the House of Representatives.

Through the 1840’s disagreements began to split the country, a process that culminated with the Civil War. Abolitionists began to find their voices and appealed to the American conscience about the moral problems with buying, selling, and driving human beings. Proud Northerners, newly prosperous in their diversified industrial economy wrongly began to criticize their southern counterparts for what they saw as inefficient and unsustainable economic practices. This Yankee pride was probably hypocritical owing to the fact that the Northern economy was largely powered by the mass of cheaply produced exportable cotton.

The deepest gash in mid-century American politics was the division over cotton’s insatiable appetite for new territory. Huge expanses of land were being appropriated by the US with the help is its army. The entire southwest part of the country and even places like Hawaii seemed promising for slavery-based agriculture. But if slavery expanded into all of the yet-to-be admitted states and territories, the resulting country would be a giant labor camp.

In addition to insisting on unlimited expansion, slave interests inspired by John C. Calhoun seized upon an idea called “substantive due process.” This was a robust idea of property rights, allegedly implied in the US Constitution, that insisted that property, read slaves, could not be seized by the government without due process which meant a jury trial. This idea was designed as a work-around the idea that the national government could designate new territory slave or free. Substantive due process protected the “right” of an enslaver to move with human property into any US territory and not have his property seized.

In the 1840’s both Northern and Southern partisans felt disempowered by the other. In many ways, the South had the upper hand and held the country hostage with the idea that “a slave West was the price of union.” Northerners also felt disempowered by fugitive slave laws which required runaways to be considered property and returnable to their masters. Southerners were economically hobbled and nervous that their slave populations got too large that bloody rebellion was inevitable. Southern leaders, even in the late 1840’s began to long for a national life that permitted unlimited expansion of slavery unmolested by Washington.

Complicated political divisions threatened to divide the country in 1848-9. To stabilize the situation Henry Clay drew up a Compromise of 1850, which attempted to deal with all open controversies in one omnibus decision. The Compromise entailed these provisions:

- California would

be admitted as a free state - New Mexico and

other Southwest lands would be organized as territories, without regard to

slavery, which would be determined later by settlers in those places. - The US would pay

debts of the Republic of Texas - Washington would

surrender power to interrupt the internal slave trade - The fugitive

slave laws were shored up

Initially the Clay’s Compromise was rejected, but Steven Douglas divvied up its provisions and got them passed separately. At the passing of the Compromise of 1850, the nation, North and South, breathed a sign of relief. But its provisions had not resolved the deeper divisions that only the Civil War could deal with. What’s more, the Compromise probably bought the Northern states an additional decade to consolidate its industrial strength so it was strong enough to defeat the South in the early 1860’s.

Chapter 10: Arms

Slavery in the 1850’s, the years leading to Lincoln’s election and the outbreak of the Civil War, had fully recovered from the twin crashes of 1837 and 1839. The economy based on enslaved workers was more profitable than ever and its proponents were beginning to pursue a vision of America as an ever-expanding slaved-based machine. The ferocity of the South’s self-assertion through the 1850’s was stunning. Slavery was hardly the inefficient relic from a primitive past that was teetering on collapse. It was, in the 1850’s a megalith of economic power that produced 4 million cotton bales in 1860 and claimed constitutional protections that nearly put it beyond Washington’s ability to rein in. Slavers and others yearned to wrest Cuba from Spain’s control either by purchase or conquest. The plan was to divide the island into three new slave states. Additionally, the Kansas Nebraska proved to be a boon for the voracious slave interests. The Act repealed the Missouri Compromise and permitted enslavers to move into any area in the former Louisiana Purchase territory with their human property. The decision whether the state would be slave or free was deferred to a later time to be decided by vote of the settlers. This clear win for the slavery interests placed a deadening hand on Northerner’s designs on Cuba.

Another development, a Supreme Court decision called the Dred Scott Case, also dampened enthusiasm for the abolition of slavery. The decision asserted among other things that the US Constitution never envisioned Black citizenship, a determination that suggested that slavery was becoming a permanent feature of American life.

The chapter’s final pages described Abraham Lincoln’s rise and election as president. Lincoln, slavery’s most persuasive and wily opponent, honed his arguments against slavery in the Lincoln-Douglas debates which preceded Illinois’ senatorial election in 1858. Lincoln later published his debate notes in a book. These ideas were the driving principles of Lincoln’s presidency and culminated in the Emancipation Proclamation and ultimately in the Thirteenth Amendment.

Afterword: The Corpse

I would summarize the Afterword as commentary on W.E.B. Dubois’ famous quote:

The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery

The first historical reality Baptist deals with is Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, whose immediate impact was to grant explicit official permission for enslaved people to leave their toil. Tens of thousands did, many of whom joined ranks with the Union Army. This willingness to fight for the United States became the number one rationale for the Fifteenth Amendment which granted African Americans the vote. After four years of war, which left 700,000 Americans dead, Union troops spread throughout the South freeing any remaining captives who had not run off during hostilities. Invariably, this freedom was greeted with jubilation.

Many elites in the South were far from jubilant and in years to come dedicated themselves to turning back any Black progress signaled by the Emancipation Proclamation or the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. Thus following emancipation, came a series of laws in the South which blocked voting and office holding, created hair-trigger arrests for vagrancy and other trivial offences, and utilized public policy to force Blacks into a subservient state that was as close to slavery as possible.

Baptist briefly describes Lincoln’s death occurring in April 1865 after being stalked by his assassin, John Wilkes Booth.

Any program to grant freed Blacks property on which they could be self-sustaining as farmers fizzled. This failure forced Blacks into the pseudo-slavery of the sharecropping system as a main form of employment and southern agricultural production. From the war’s end until about 1870 there was exhilarating progress for many of the 4 million who had been trapped in the vast southern labor camp. After that, with the withdrawal of Union troops and emancipation fatigue in the North, liberation for the former captives came to a halt and then went backwards. Jim Crow and the KKK plus a succession of disappointing political developments created a post war South that was a nightmare for its Black residents.

Baptist lays out on his last pages his main thesis, namely that slavery was a huge capitalist enterprise that lifted the United States into the industrial age. The value of the 4 million captives themselves was the was the largest single category of capital in the country. The cotton produced by this army of laborers was America’s largest export and the 19th century’s key commodity which powered the industrial revolution and clothed the world.

It is an important theme of Baptist’s book that slavery, as practiced in the American Southwest, was no primitive agricultural practice, woefully inefficient and destined for extinction. Rather, the cotton industry was capitalist in every respect. It was increasingly efficient and adaptive. Slavery re-invented itself in the early 1800’s, relocated, attracted increased and stable financing and was growing. It would not die on its own. Only a war could halt its advance and profitability.

2 Replies to “THE HALF HAS NEVER BEEN TOLD: Summary and Notes”

Thank you Doug for your very informative summary. The graphics are especially excellent for those of us who use Audible Books to complete our reading assignments. This book is full of discoveries about slavery and american history.

Thank you Doug Very informative.